A Coastal Community Combining New Development with Historic Character and Natural Beauty

By Christina Butler/Butler Preservation LC for Charleston Empire Properties

03 August 2020

John’s Island on the 1919 USGS Topographic Survey Map.

John’s Island was home to the Cusabo, Kiawah, Stono, Bohicket, and affiliated Native American tribes when the English arrived in the late seventeenth century to settle on land granted to them by the Lords Proprietors. The Colleton family (for whom Colleton County is named) came by way of Barbados and brought enslaved people of African descent with them, setting the tone for plantation development on Johns and surrounding islands. In 1739, a slave named Jemmy led the Stono Rebellion, one of the largest slave insurrections in South Carolina history, from Johns Island, where they crossed Stono River and headed toward Charleston.

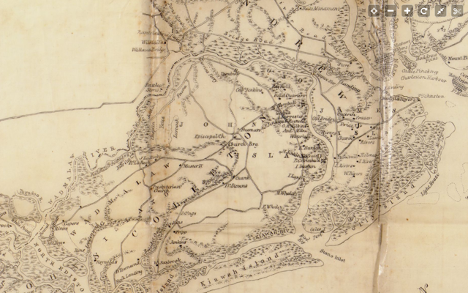

Johns Island pictured on the 1711 “Crisp Map”, bounded by “Keyaway” and Boones (James) Islands.

The Stanyarnes and Godfreys were some of the earliest settlers, receiving land grants for vast acreage in 1698. In the eighteenth century, the Mathews and Stanyarne family owned large tracts of land on Johns Island, including Mathews Place and White Hall plantations, and the Holmes, Fenwick, Gibbes, Jenkins, and Legare families were also large land holders on the island. Most early Johns Island planters had town properties and conveyed their goods and themselves to Charleston via the waterways linking the town and the islands. The Stono River, which borders the island and is part of the Intracoastal Waterway, has been an important transportation route since the earliest habitation. By 1707 the Kings Highway afforded an overland option. Besides traveling to Charleston for balls and social events, the elites of Johns Island entertained themselves at home with outdoor activities which still common in the Lowcountry, such as hunting, shooting, and riding, and the earliest race horse breeding in the southern colonies took place on Johns Island.

Johns Island on the Mills Atlas of 1825. The Jenkins, Legare, and Whaley family lands are shown, as is Headquarters plantation near the Stono River.

Peaceful Retreat, Brick House, and Mullet Hall are just a few historic plantations whose grounds are partially intact today. Historic architectural highlights include Johns Island Presbyterian Church (a very early wood frame building dating to 1719 and expanded in 1792 and 1823) and Fenwick Hall, an early eighteenth century rice plantation with Georgian style brick house that is similar in age and grandeur to famous Drayton Hall, with two formal facades (one facing the road and one looking onto the river). Johns Island was an important strategic coastal site during the American Revolution, and when Sir Henry Clinton occupied the island in 1780 he made Fenwick Hall his base, leading to the plantation’s second name, Headquarters. Fenwick is still privately owned.

Fenwick Hall in the 1940s. Library of Congress

Johns Island was rural plantations for most of its history, and the majority enslaved population made the elite planters extremely wealthy. Sea Island cotton and rice were the most important cash crops for much of the colonial and antebellum era.

A map of Johns and Wadmalaw Island by Kinsey Burden, 1820s, showing the plantations. Note the population of the island is listed as “190 whites, 2,666 Negro slaves, and 6 free negroes.”

During the American Civil War, the Union forces did considerable damage on Johns Island as they tried to take Charleston, burning several plantation houses, outbuildings, and crops as they marched through.

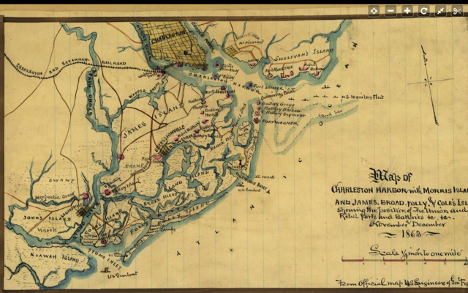

A map of Johns Island and Charleston from 1863 during the Civil War.

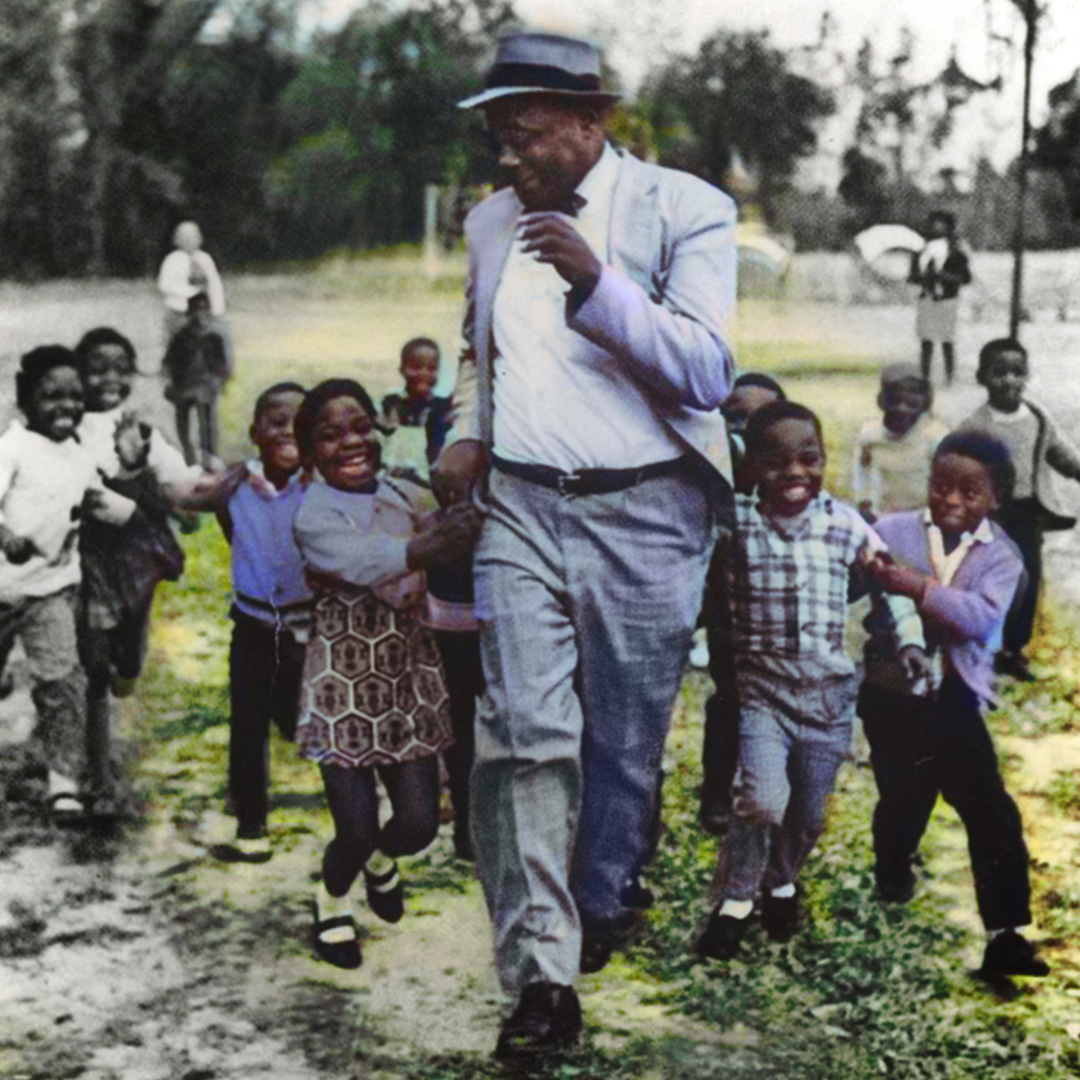

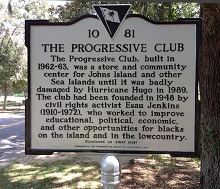

Reconstruction brought important changes for Johns Island’s black population. The Freedman’s Bureau redistributed plantation land seized from Confederate owners and granted it to the freed populations who had worked the land as slaves, leading to several important freedman communities which have remained in the same families of since the 1860s. Black Johns Islanders also started their own church congregations, including Mt. Hebron Presbyterian on Bohicket Road (built in 1865) and Promised Land Episcopal (1875.) Alongside black landownership, exploitive farming practices like tenant farming and share cropping became common for African American families on the sea islands as white owners began to reclaim their former plantation lands. Decades later, famous civil rights leaders Septima Clark, Bill Saunders, and Esau Jenkins established the Progressive Club in the 1940s to uplift black islanders. The Club offered education, citizenship classes, and voter registration for the island’s disenfranchised black population, and a consumer co-op with a grocery store and gym. The building is awaiting restoration, but the Club is still active on the island and working to protect black landowners’ heritage.

(Left/Top Image) Esau Jenkins at the Progressive Club; a state historical marker. www.Progressivclub.org

The town of Maryville sadly lost is charter in the 1936, about fifty years after its incorporation, when four white store owners in the 500 person, majority black community disputed having to pay local taxes. The News and Courier noted, “The effort to abolish this township has been a long one. The town was incorporated about 50 years ago, and its charter was saved in 1933 when town officials agreed not to levy a 5-percent tax on the town's merchants, most of them white." Mayor Thomas Carr, a black carpenter, and his aldermen were forced out of office, giving up their leadership of what was at that time the small municipality in Charleston County, and one of the only with black leadership.

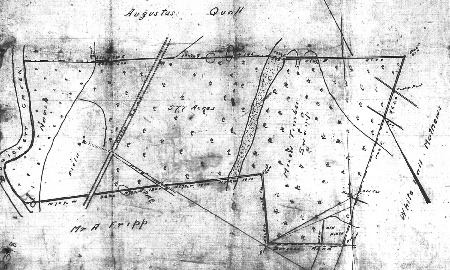

McCrady plat 2348 from the early twentieth century, showing a former plantation site with truck farm fields and timber lands.

Even after the Johns Island bridge was constructed to connect to James Island in 1921 (replaced with the John F. Limehouse Bridge in 1958, named for a well-known ferry and general store operator), the island remained rural and isolated. Cotton was farmed into the early twentieth century, before timbering and vegetable farming began to take over (the island is well known for its delicious tomatoes.) The Limehouse family still operates a farm on the island today and sources the best Charleston restaurants with their local fare. Visitors and residents enjoy local cuisine at the Tomato Shed restaurant and can pick up fresh local seafood and groceries from the Rosebank Farms roadside market.

John’s Island fields with the river in the background. Library of Congress.

(Left/Top Image)The porch at Tomato Shed café, and the entry sign for Rosebank Farms.

Today, one third of the island is in the Charleston city limits (which has led to the recent explosion of development which includes new suburban communities at almost any price point, but all near picturesque historic roads and landscapes). St. John’s Woods, Riverview Farms, St. John’s Crossing, and Headquarters (named for the historic plantation on which it is located and popular for its marsh views) are some of the most popular new communities, with wood frame houses in a variety of neotraditional, eclectic styles and sizes. Unincorporated areas remain more rural.

(Left/Top Image)A lovely house with outbuilding on Hamilton Road and a 1940s cottage on Koger Lane, both currently listed

A new Charleston single house inspired residence on the market in The Villages, St. Johns Woods.

Johns Island’s diverse neighborhoods and subdivisions are all close to historic amenities, parks, and beautiful natural resources. Thanks to its relatively late development, the island has several conserved areas that are home to hundreds of bird species, alligators, deed, bobcats and wild hogs, and is laden with marshes and rivers brimming with oysters, shrimp, and fish. Angel Oak Park boasts the oldest oak east of the Mississippi (around 500 years old). Equestrians can show and trail ride at Mullet Hall, formerly a Legare plantation and now a county park. The island also has its own library branch and several schools to choose from. John’s Island offers something for everyone, from young families to retirees, and is a safe, picturesque community with a historic legacy and natural beauty abounding.

Sources:

– Charleston Evening Post. “The John’s Island Way.” 15 April 1911.

– Elizabeth Stringfellow. A Place Called St. John’s. Reprint Company, 1998.

– Christina Butler. “The Legend of Fenwick Hall”. Kiawah Legends. Vol. 29, 2018.

– Christina Butler/Butler Preservation. Research for Brick Chimney Far, Bohicket Road. June 2018.

– Johns Island State Historical Marker.

– Connie Walpole Haynie. John’s Island. Charleston: Arcadia Press, 2007.

– Crisp, Edw, Thomas Nairne, John Harris, Maurice Mathews, and John Love. A compleat description of the province of Carolina in 3 parts: 1st, the improved part from the surveys of Maurice Mathews & Mr. John Love: 2ly, the west part by Capt. Tho. Nairn: 3ly, a chart of the coast from Virginia to Cape Florida. [London: Edw. Crisp, ?, 1711] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004626926/.

– Sneden, Robert Knox. Map of Charleston Harbor with Morris Island and James, Broad, Folly, and Cole's Islds.: showing the position of the Union and Rebel forts and batteries & & November and December. [to 1865, 1863] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/gvhs01.vhs00267/.

– Johnston, Frances Benjamin, photographer. Fenwick Hall Plantation, John's Island, Charleston County, South Carolina. Charleston County John's Island South Carolina United States, 1938. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017889498/.

– Highsmith, Carol M, photographer. Aerial view of the Johns Island terrain south of Charleston, South Carolina. Though it's South Carolina's largest, Johns Island doesn't look like much of an island, since most of its border is created by small streams. Johns Island was named after Saint John Parish in Barbados by the first settlers to the island. Johns Island Johns Island. South Carolina United States, 2017. -05-01. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017879869/.

– Stringfellow, Elizabeth. A Place Called St. John’s: The Story of Johns, Edisto, Wadmalaw, Kiawah, and Seabrook Islands of South Carolina. Reprint Company, 1998.

– Christina Butler. “The History of Fenwick Hall: A Legendary Johns Island Plantation.” Kiawah Island Legends, June 2017

– Leiding, Harriet Kershaw. Historic Houses of South Carolina. Philadelphia: Lippincott Company, 1921

– Mills, Robert, Charles Blacker Vignoles, and Henry Ravenel. Charleston District, South Carolina. [1825] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2006636553/.

– Stockton, Robert. Fenwick Hall, Stono River, Johns Island, South Carolina: Historic and Architectural Documentation. Charleston: self-published, 2002.

– Guy and Candie Carawan. Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life? The People of Johns Island South Carolina: Their Faces, Their Words, and Their Songs. Athens: University of George Press, 1989.

– Preservation Consultants Inc. James Island and Johns Island Architectural Inventory. City of Charleston, 1989. http://nationalregister.sc.gov/SurveyReports/HC10002.pdf

– Charleston Progressive Club, http://progressiveclub.org/our-history/