Radcliffeborough: Residential Character, Religious Architecture, and Register Listed Properties

By Christina R. Butler/Butler Preservation LC for Charleston Empire Properties – 22 January 2020

Radcliffeborough is a small but vibrant neighborhood in Charleston’s historic district, bounded on the south by Calhoun Street, north by Morris Street, east by King Street’s bustling restaurant corridor, and on the west by Ashley Avenue and the Medical district; in fact, its residents are a diverse mix of health care professionals, medical students, and longtime Charlestonians, with a sprinkling of corner stores and small neighborhood shops. The roughly 84 acre neighborhood is brimming character and boasts several National Register listed historic properties making it a key area for Radcliffeborough Charleston SC real estate.

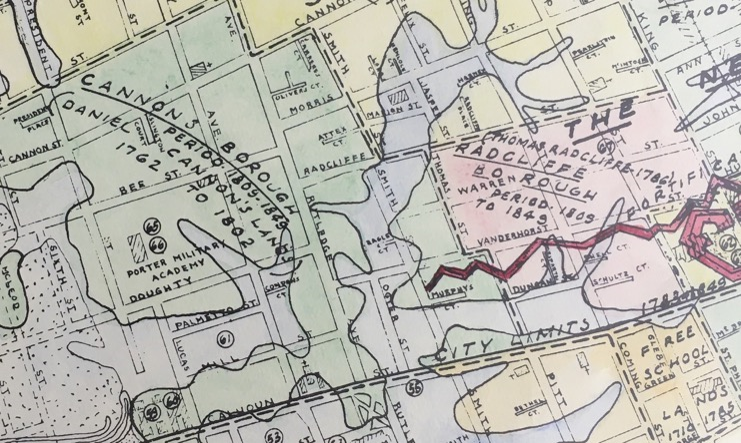

Radcliffeborough Charleston SC Real Estate & Homes for Sale: The 1949 Halsey Map showing Raclifeeborough and mills of Cannonsborough to the west

The land that became Radcliffeborough began as rural property dotted with marshes and tidal creeks, just outside of the town limits. Thomas Radcliffe (1740-1806) owned the tract and subdivided it to create his namesake neighborhood in 1786, although most of the area’s architecture dates from the early nineteenth century forward. Sadly, Radcliffe was lost at sea in 1806, but his young widow Lucretia continued to sell and develop the lots as home for sale in Radcliffeborough flourished. She also donated the land on which St. Luke and St. Paul’s Episcopal Cathedral is located. The grand church was designed and built by the Gordon brothers from 1811 to 1816.

Radcliffeborough Charleston SC Real Estate & Homes for Sale: Cathedral of St. Luke and St. Paul, Coming Street

West of Ashley Avenue near Calhoun Street was historically home to several rice and lumber mills, with mill buildings, causeways, millponds, and wharves to receive goods coming in via the Ashley River. The vestiges of the Ashley River marshes and millponds were slowly filled in the nineteenth century. For example, the city filled one of the last remaining ponds in Radcliffeborough, bounded by Vanderhost, Smith, and Rutledge Streets, in 1871 to create more buildable land, and Ashley Avenue (originally Pinckney Street) was extended north and southward. The area quickly filled with fine Victorian houses.

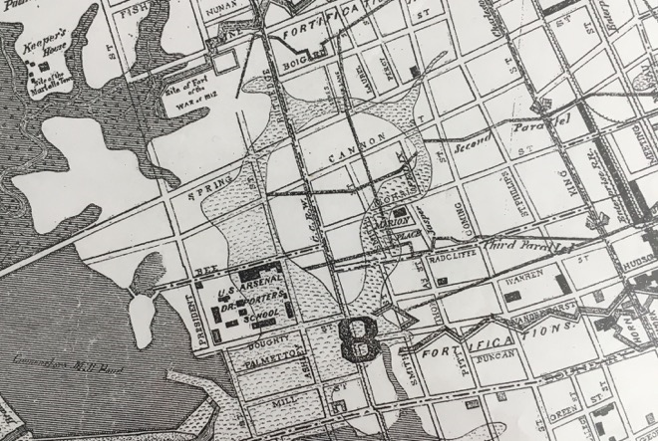

A city plat showing the western edge of the neighborhood.

Radcliffeborough Charleston SC Real Estate & Homes for Sale: Radcliffeborough in 1883, showing the former adjacent marshes and ponds.

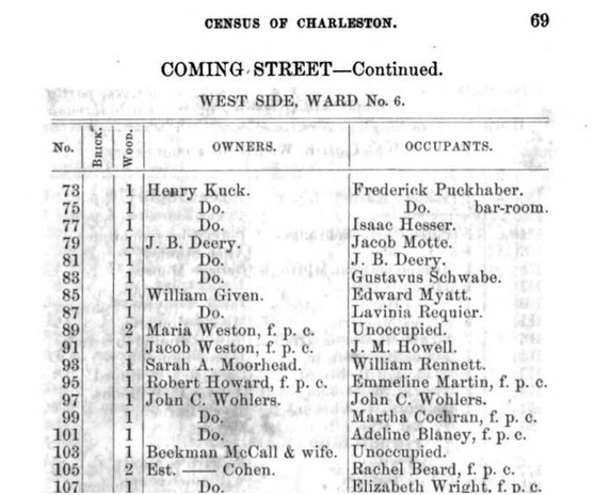

Radcliffeborough’s population was historically very diverse, with a number of elites, middle class tradesmen, free people of color, and slaves living in rented spaces away from their owners in the antebellum era. As a result the architecture is diverse as well and ranges from small freedman’s cottages along Morris Street to single houses built as tenements and now duplexed as apartments and condos, to grand estates. Duncan and Coming Streets became home to several smaller rental houses.

Coming Street in 1861, with several free people of color (f.p.c.) in residence.

A unique L-shaped freedman’s cottage on Duncan Street.

Radcliffeborough also has several fine mansions with large yards and outbuildings that would have been summer homes to planters and merchants. The Duncan-McBee house is probably the best example, built by Patrick Duncan around 1802 in the Regency style and converted into the prestigious Ashley Hall girls’ school in 1909. The Wickliffe house at 178 Ashley Avenue was built around 1850, by the Jonathan Hume Lucas, whose family owned mills to the west of Radcliffeborough. The house features a large southern facing yard and Tower of the Winds columns on the large portico. If you’re interested in exploring Radcliffeborough Charleston SC real estate these historic homes offer a glimpse into the area’s rich architectural heritage.

The McBee House and an antebellum mansion with gallery doors onto wide piazzas.

Radcliffeborough is also home to several historic churches. After the American Civil War, a group of elite Radcliffeborough African Americans founded St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, a unique wood frame Roman Revival building designed by noted architect Louis Barbot in 1875. Nearby is St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church, which was founded by Charleston’s Irish in 1838 and became a diverse mixed race church. The current building was completed in 1891. Around the corner on Radcliffe Street is Central Baptist, built by an African American congregation in 1893 and best known for its iconic “Jesus Saves” message on the bell tower. These churches add to the cultural richness of homes for sale in Radcliffeborough.

St. Patricks, St. Mark’s, and Central Baptist Churches.

Like so many downtown neighborhoods across the United States, Radcliffeborough lost much of its population in the 1950s and 1960s to the new suburban communities outside the city center, but was one of the first to rebound and has been a desirable part of downtown since the 1970s. Today, the land to the west of is dominated by the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) campus, which is a nationally renowned hospital network and teaching facility. The campus is comprised of modern buildings, as well as historic residences that have been purchased, renovated, and absorbed into the MUSC complex. College of Charleston bounds to the south. Although framed by these important institutions, Radcliffeborough remains mostly residential and peaceful and is an ideal part of the peninsula for residents desiring large yards and a suburban, peaceful vibe while being a stone’s throw from the heart of the city.

Sources:

Burton, Milby, ed. Streets of Charleston, Vol. 1-2. Charleston: Charleston Museum, 1980.

Butler, Christina. Lowcountry At High Tide. USC Press, 2020.

Butler, Nicholas. “Grasping the Neck.” https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/grasping-neck-origins-charlestons-northern-neighbor

Butler, Nicholas. “Mr. Duncan’s Trees.” https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/mr-duncans-trees

City of Charleston. Census of Charleston for the Year 1861. Charleston: Walker and Cogswell, 1861.

Charleston Evening Post. Charleston, S.C.: its advantages, its conditions, its prospects. A Brief History of the “City by the Sea.” Charleston, 1898.

City Engineer’s Plat Book, 1670-1949. Charleston Archive, Charleston County Public Library.

Poston, Jonathan. Buildings of Charleston. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps. Charleston, 1888-1955. Accessed through www.ccpl.org, March 2019.

Smith, Alice Ravenel Huger. Dwelling Houses of Charleston, South Carolina. Charleston: History Press, 2007. Reprint.

Thompson, Jack. Charleston at War: A Photographic Record, 1861-1865. Gettysburg: Thomas Publications, 2000.

Vertical file, Radcliffeboroough, South Carolina Room, Charleston County Public Library.

News and Courier, “Radcliffeborough Homes next stop on fall tour.” 6 October 1988.