Hampton Park Terrace: Charleston City's Beautiful neighborhood

By Christina R. Butler/Butler Preservation for Charleston Empire Properties – 22 December 2019

Bounded by Congress Street to the south, Rutledge Avenue to the east, the Citadel campus to the west, and Mary Murray Drive on the north, Hampton Park Terrace is a historic Charleston neighborhood bordered and defined by the largest green space in the city, circa 1902 Hampton Park. Both the park and the Terrace neighborhood were inspired by the City Beautiful movement of the early twentieth century, a national push to beautify urban areas, create parks and recreational amenities, and to lay out pleasant suburbs with access to nearby greenspace. The concept was popular with Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., whose firm designed Charleston’s own Hampton Park.

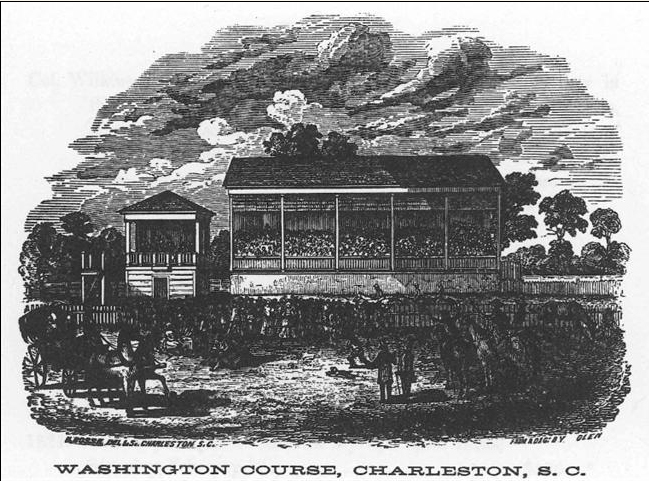

The land that became Hampton Park Terrace was rural until the late nineteenth century, owned by Daniel Legare in the colonial era, and then purchased by the Honorable Langdon Cheves. Neighboring Hampton Park has had many lives, transforming from a rural marshland to horse racing course, to a Union prisoner of war camp and cemetery in the Civil War, to a fair grounds, before becoming a well-manicured park with trails, sports fields, reflecting ponds, and beautiful planting beds under live oaks. Hampton Park was owned by John Gibbes in the 1770s and was part of the Grove Plantation. The Jockey Club acquired the land and created the Washington Race Course, which operated from 1794 until circa 1882.

1883 Map of Charleston, showing the Washington Race Course, Gibbes’ former plantation site, and the surrounding streets that would later become Hampton Park Terrace.

Library of Congress engraving of the race course stands.

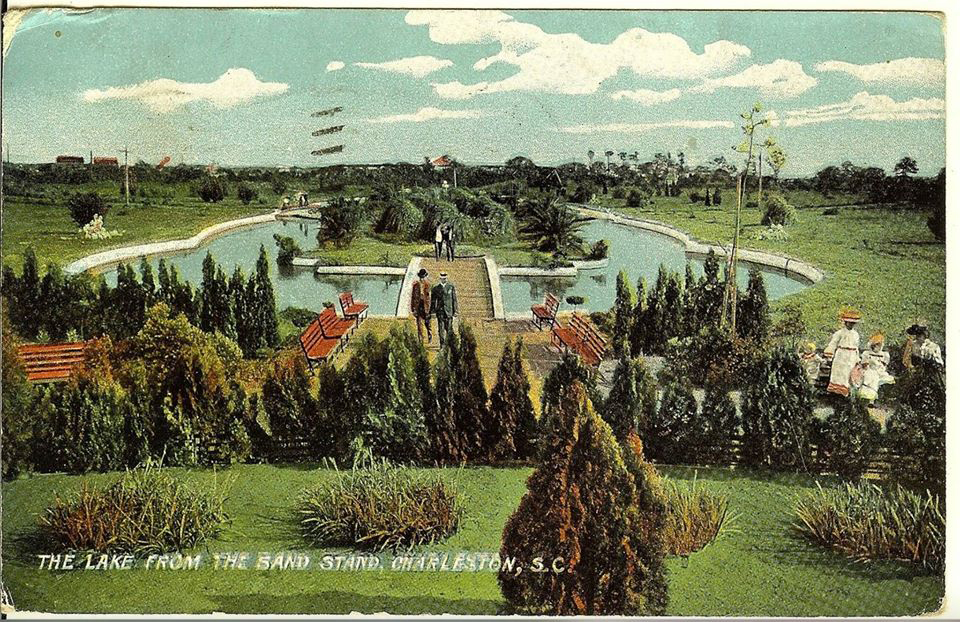

In 1901, the race course and part of Wagener’s Farm became the site of the South Carolina Interstate and East Indian Exposition, a World’s Fair style year-long event designed to showcase Charleston’s amenities and boost the economy by enticing new businesses and tourists. The City of Charleston purchased the site the following year and hired Olmsted Brothers Landscape Architects to convert it into a park; the sunken gardens and gazebo are vestiges of the fairgrounds that were incorporated into the new plan.

Hampton Park on a 1911 map of the city.

1907 postcard of Hampton Park’s sunken gardens, and the bandstand today.

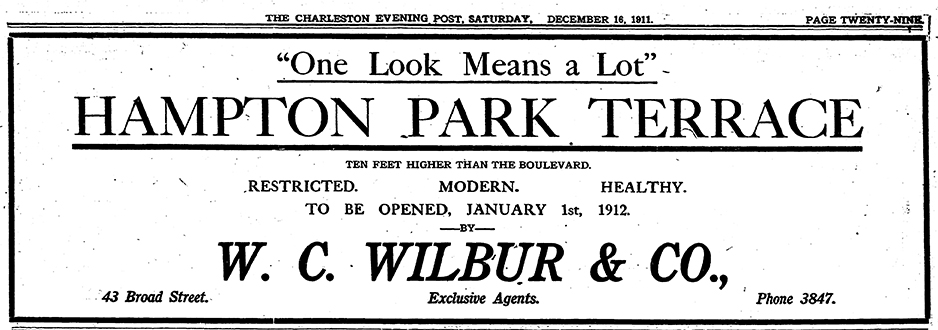

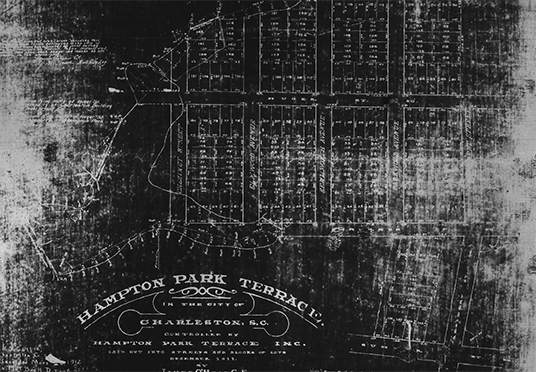

As the Navy Base in North Charleston expanded leading up to World War One, rural areas on the upper peninsula became desirable for new house sites. Hampton Park became a perfect anchor for the new Hampton Park Terrace subdivision, created in 1911 and financed by W.C. Wilbur and Company and Charleston Building and Investment Company (owned by James Allan, of Allan Farm, where part of the new neighborhood would be built.) The developers laid out Kenilworth, Elmwood, Parkwood, and Chestnut Street to compliment preexisting Congress, Huge, and Moultrie Streets. Like many subdivisions of the Jim Crow era, Hampton Park originally had covenants to ensure that the area would be home to the white middle class; deeds stated that houses could not be ‘sold, rented, or otherwise conveyed to persons of African descent”, and new houses must cost at least $1800 to construct. Fortunately, these clauses were no longer effectual after the Civil Rights area, and Hampton Park Terrace became a more integrated neighborhood. The neighborhood attracted white collar residents including doctors and bankers, and both the Wilbur and Allan families both constructed homes in their new subdivision.

Mccrady plat 2933, original subdivision

By 1915, almost half of the 251 lots had sold, and nearly 200 houses had been built by 1922. The neighborhood was located on the streetcar route, allowing residents to easily commute to work, and real estate ads boasted, “no more desirable location for a home could be imagined-close to the river, away from the noise and bustle of the city, on the Rutledge avenue [trolley] car line and close to the King street car line, bordering Hampton Park, beautiful now and to be doubly beautiful when plans now being worked out are completed, within sight of the Ashley River with its fresh salt breezes, and the whole area high and dry, sixteen feet above low water mark.” Houses are situated on large lots along tree lined streets, and come in a range of plans and styles from Four-square Arts and Crafts, to late Queen Anne Victorian, bungalows to Colonial Revival, and even a few diminutive Freedman’s cottages along Huger Street.

Cannonborough-Elliottborough became a diverse neighborhood with a mixture of industrial businesses, large “urban plantations” with fine gardens, modest farms, and small cottages and tenements. Irish and German immigrants, Jewish residents, free black, enslaved, and native born white artisans called the area home in the nineteenth century.

By the 1840s, residents in Cannonborough were petitioning the city for new streets to better connect their area with denser development in the original town.

“Roanoke plan” Sears and Roebuck kit house, 207 Congress Street.

Hampton Park was designated as a National Register historic district in 1997, attesting to the unique and intact character of the neighborhood. Today it remains a residential neighborhood close to parks and businesses on Rutledge Avenue, but with a uniquely quiet suburban feel that is hard to find so close to the heart of the city.

To learn more about life in the Hampton Park Terrace, Charleston and the available real estate, give us a call at Charleston Empire Properties. We enjoy sharing information about our city, and we would be excited to show you around this historic and culturally rich neighborhood. We stay current on all the real estate in Hampton Park Terrace, as well as other listings in the surrounding area, and we can easily show you what is currently available. Give our agents a call today or download our mobile app to start viewing real estate in the beautifully historic Hampton Park Terrace neighborhood.

Sources:

- Charleston County Public Library. Vertical files: Neighborhoods: Hampton Park Terrace.

- Charleston News and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina, 1803- present. (Renamed Charleston Post and Courier in 1996.)

- Christina Butler. Lowcountry At High Tide. USC Press, 2020.

- Deborah Lynn Rhoad. One Look Means a Lot: the development of Charleston’s early twentieth century suburbs, 1915-1935. Master’s Thesis, College of Charleston, 1995

- Kevin Eberle. A History of Charleston’s Hampton Park. Charleston: History Press, 2012.

- National Register nomination, Hampton Park Terrace, 1997.

- Historic maps and plats