Charleston is the birthplace of the historic preservation movement in America, boasting many firsts, from the first historic district in the nation to the premier community-based preservation organization. In this blog, we’ll introduce Charleston’s preservation groups, the city’s architectural review process, initiatives, and awards that homeowners of historic Lowcountry property owners can apply for.

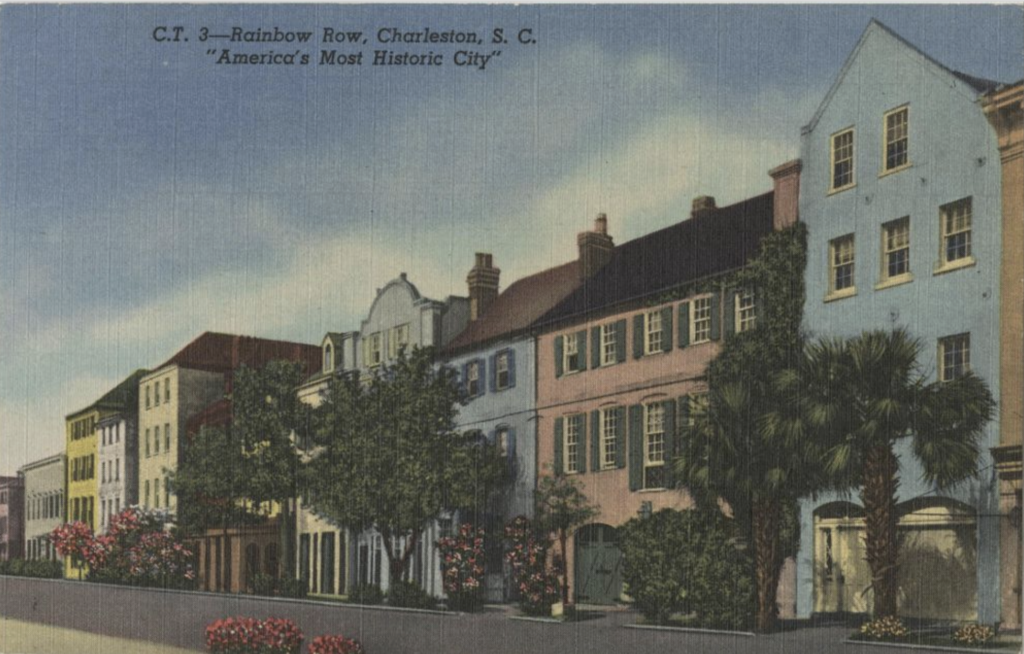

Lowcountry residents have always revered their history and unique architectural fabric. As cities across the United States were modernizing and destroying historic fabric, and New South cities like Atlanta were growing, Charleston remained economically depressed and almost frozen in time. Recognizing that the city and its surrounding Lowcountry landscape was unique, it didn’t take long for locals to step forward when several important houses were lost in the 1920s to parking lots and gas stations. The Preservation Society https://www.preservationsociety.org was founded in 1920 and remains “dedicated to the preservation and enjoyment of Charleston’s distinct character, quality of life, and diverse neighborhoods.” Susan Pringle Frost founded the society to save the Joseph Manigault house, which was slated for demolition in an era where there was no legal protection for historic buildings. She was successful, and today the Manigault house is a house museum operated by the Charleston Museum. Recognizing that saving a neighborhood takes more than saving one house at time, the Society turned to their city council for support.

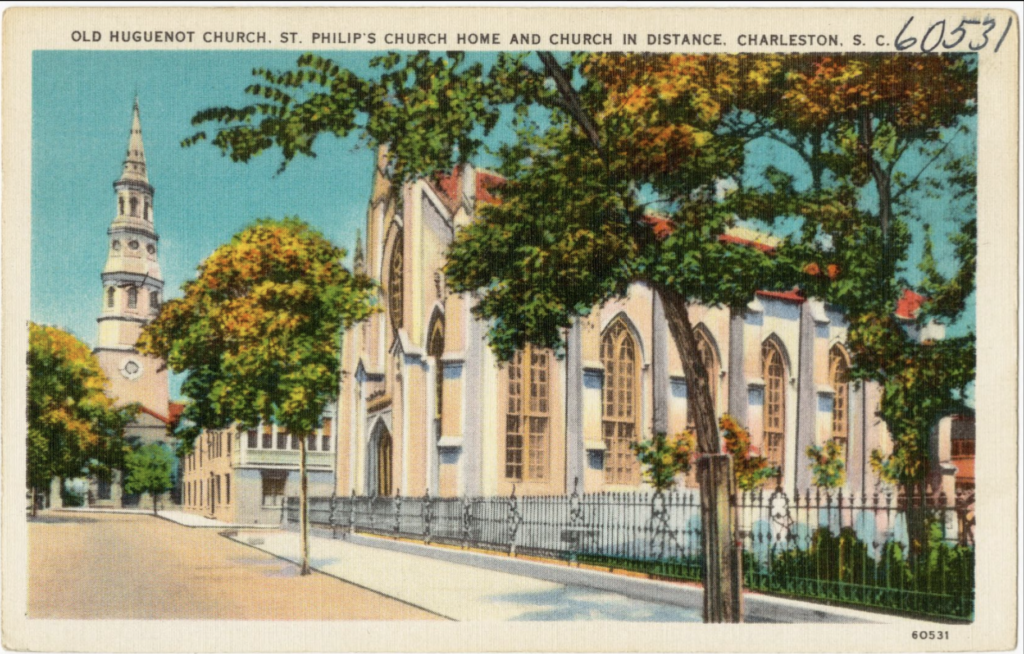

The City of Charleston boasts the largest and first historic district, first designated in 1931 by city ordinance and expanded several times since to include most of the Charleston peninsula south of Line Street. The city’s Board of Architectural Review has existed ever since for, “the preservation and protection of the old historic or architecturally worthy structures and quaint neighborhoods which impart a distinct aspect to the city, and which serve as visible reminders of the historical and cultural heritage of the city, the state, and the nation.” The BAR regulates additions and exterior alterations to buildings within the historic district, prevents the demolition of historic buildings, and approves all new construction within the district. Minor alterations, repainting, and simple repairs are reviewed and approved by the city’s preservation staff at the Gaillard Center at 2 George Street, which is usually a quick and straightforward process.

BAR Large reviews projects over 10,000 square feet while BAR Small tackles most residential projects. There are also historic overlay zones with some preservation jurisdiction, so homeowners should consult the city’s helpful website before embarking on work. Click here for a jurisdiction map: https://www.charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/1270/Historic-Districts-Purview-Map–color-2020?bidId= . It’s also important for potential buyers to note that many communities in Charleston County have some preservation oversight, not just the peninsula. For example, Mount Pleasant has a historic commission, and the Town of Sullivan’s Island has a Design Review Board to protect the island’s unique architectural fabric.

Owning a historic house isn’t just about following extra rules, there are benefits to living in a piece of history. Occasionally, there is tax credit money available through the State Historic Preservation Office for qualifying projects (especially those within National Register historic districts) to help offset the costs of renovations, so be sure to visit https://scdah.sc.gov/historic-preservation/programs/tax-incentives to learn more. The City of Charleston (which includes much of West Ashley, James Island, Johns Island, and Daniel Island) also has a helpful guide to financial resources for preservation: https://www.charleston-sc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/32849/Financial-Resources-for-Historic-Preservation-2022

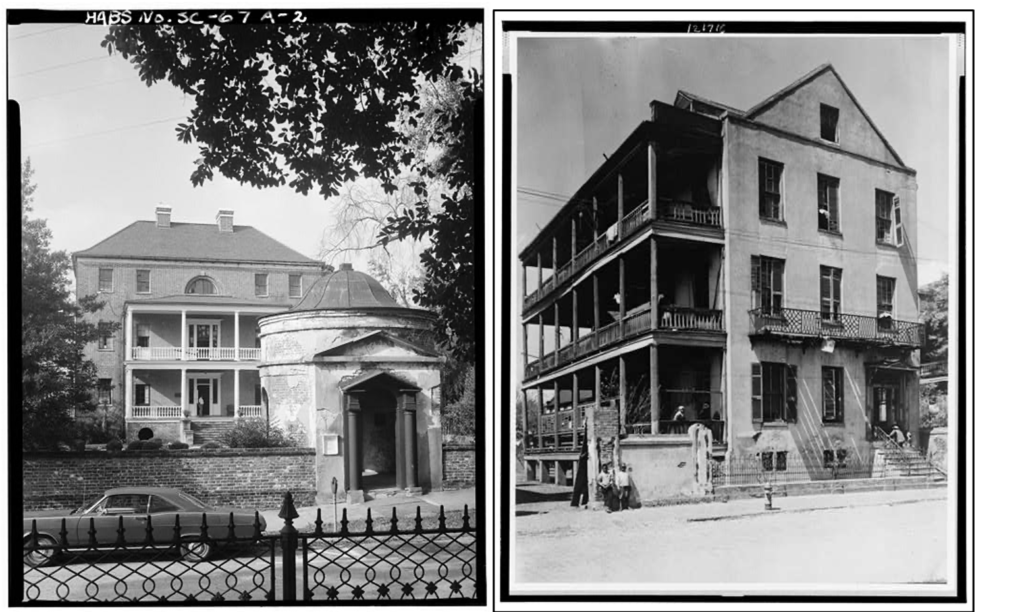

Founded in 1947, the Historic Charleston Foundation is another important preservation group. Their website explains that as Charleston have evolved, “the Foundation has broadened its scope into balancing the needs of modern society with protecting the sensitive fabric of the historic district.” They operate two important house museums (one restored to 1808 grandeur and the other in a preserved state), and like the Preservation Society, they attend most city planning, zoning, and BAR meetings to monitor upcoming projects. In the 1950s, HCF used a groundbreaking revolving fund to restore Ansonborough, a downtown neighborhood that is home to a large collection of antebellum buildings, HCF, “began buying batches of houses, partially restoring them, placing protective covenants on them and selling them to preservation minded buyers, and then taking the proceeds to purchase the next round of houses. Through their focused long-term plan, the Ansonborough Rehabilitation Project, HCF renovated and restored over 80 houses by the 1970s.” Ansonborough gentrified and became part of the historic district, losing much of its cultural diversity along the way. Preservation groups have since come to recognize that neighborhoods are made of architecture and people, and communities must also be preserved.

As Charleston County grows ever more popular, city-based advocacy groups are joined by land conservation non-profits such as Edisto Island Open Land Trust, who work to control development and save our coastal landscapes. EIOLT conserves nearly 5,000 acres and is in the process of restoring Hutchinson House, the oldest intact residence built by freed people on the island in the Reconstruction era. Click https://edisto.org/land/ to learn more. Coastal Conservation League also works diligently to “protect the health of the natural resources of the South Carolina coastal plain and ensure a high quality of life for all the people who live in this special place”, through a host of initiatives including advocacy work and conservation easements.

Advocacy staff from HCF and the Preservation Society attend virtually every city planning, zoning, and preservation meeting to monitor upcoming projects, keeping a pulse on the rapidly changing city skyline and surroundings for its members. HCF notes that, “communities must be vibrant to survive. With vibrancy comes inevitable growth and development. Our mission is to address modern society’s needs – mobility and transportation, tourism, livability and growth – while protecting and preserving the architecture and material culture of Charleston and its Lowcountry environs. Historic Charleston Foundation champions the historic authenticity, cultural character and livability of the Charleston region through advocacy, stewardship and community engagement.” Most local advocacy groups today are also concerned with balancing tourism so visitors and locals alike can enjoy this special place. Current projects on the horizon to watch are the development of the Union Terminal, an active port operated by the state and a cruise ship terminal that is slated for redevelopment (learn more here: https://www.unionpiersc.com) and the lawsuits surrounding 295 Calhoun Street, a large proposed new building on the edge of Harleston Village.

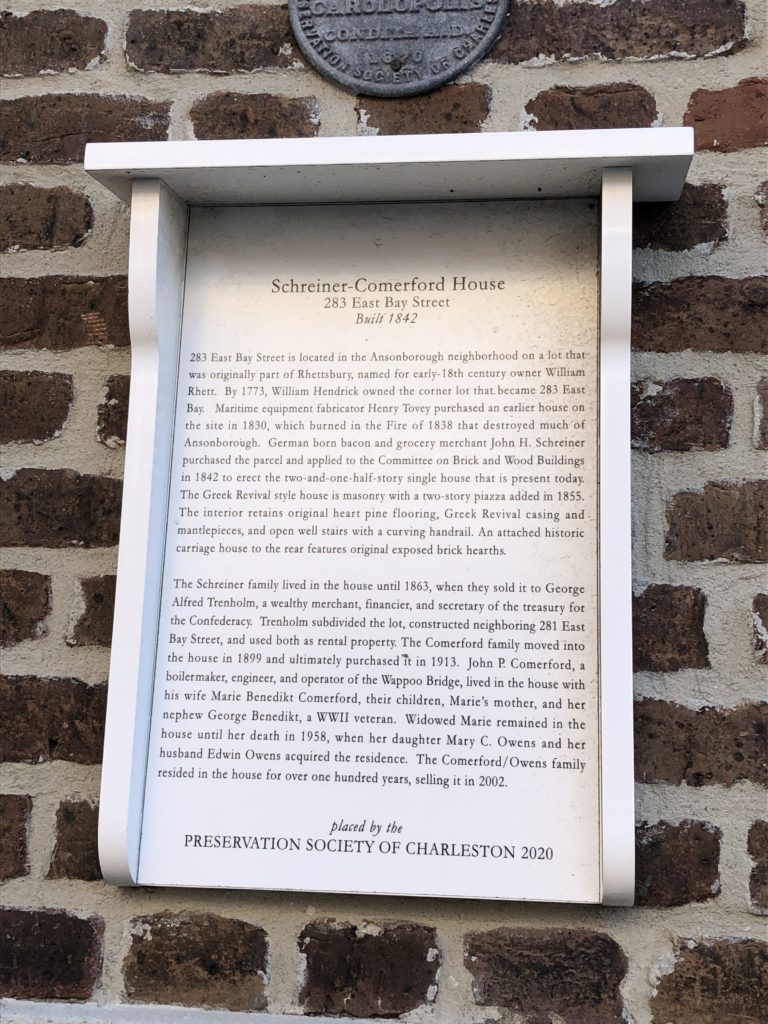

Aside from advocacy work, the Preservation Society has a historic marker program to help educate people about Charleston’s many unique buildings, and they sponsor the Carolopolis Award to “promote excellence in historic preservation through recognition of exceptional projects that protect the historic resources of Charleston and the Lowcountry. Categories include new construction, restoration, preservation, interior, pro merito (for continuing expert maintenance of an award winning property at the 25 year mark), and resilience (for best practices responses to changing climate). The awards can increase property value, in addition to providing much-deserved bragging rights!

Spring in Charleston is a beautiful time of year to learn more about preservation by attending any of the amazing house tours, lunch lectures, guided walks, or garden tours hosted by Historic Charleston Foundation as part of the Festival of Tours, so be sure to view their offerings (and keep in mind- members get a discount!): https://www.historiccharleston.org/blog/events/category/festival-of-houses-gardens/ And each fall, there’s another fabulous array of private tours hosted by the Preservation Society, so be sure to check their website.

Sources:

- https://www.preservationsociety.org

- https://www.historiccharleston.org

- Christina Butler. Ansonborough: From Birth to Rebirth. Charleston: Historic Charleston Foundation, 2019.

- Robert Wyeneth. Preservation For A Living City: Historic Charleston Foundation. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

- Stephanie Yuhl. Golden Haze of Memory: The Making of Historic Charleston. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- https://www.charleston-sc.gov/293/Board-of-Architectural-Review-BAR-L-BAR-

- https://edisto.org

- Christina Butler. “Ansonborough: Antebellum Architecture at its Finest.” Charleston Empire Properties blog. https://charlestonempireproperties.com/ansonborough-antebellum-charleston-architecture-at-its-finest/

- “Last Black Homeowners Leave Ansonborough Neighborhood.” Post and Courier, 6 August 2022.

- https://www.coastalconservationleague.org

- Jennifer Billock. “The Suffragist with a Passion for Saving Charleston’s Historic Architecture.” Smithsonian Magazine. 23 March 2020.