Ansonborough: Antebellum Charleston Architecture at its Finest

By Christina R. Butler/Butler Preservation for

Charleston Empire Properties – 3 June 2020

Hasell Street in 1902. Library of Congress.

Ansonborough today encompasses several smaller colonial era developments, just north of the original town boundary where Hasell Street lies. Rhettsbury, the earliest settlement, dates to 1699. It originally included the land that is now Hasell and Wentworth streets. Its focal point was the William Rhett house at 54 Hasell Street, oldest residential building in the city, dating to 1712.

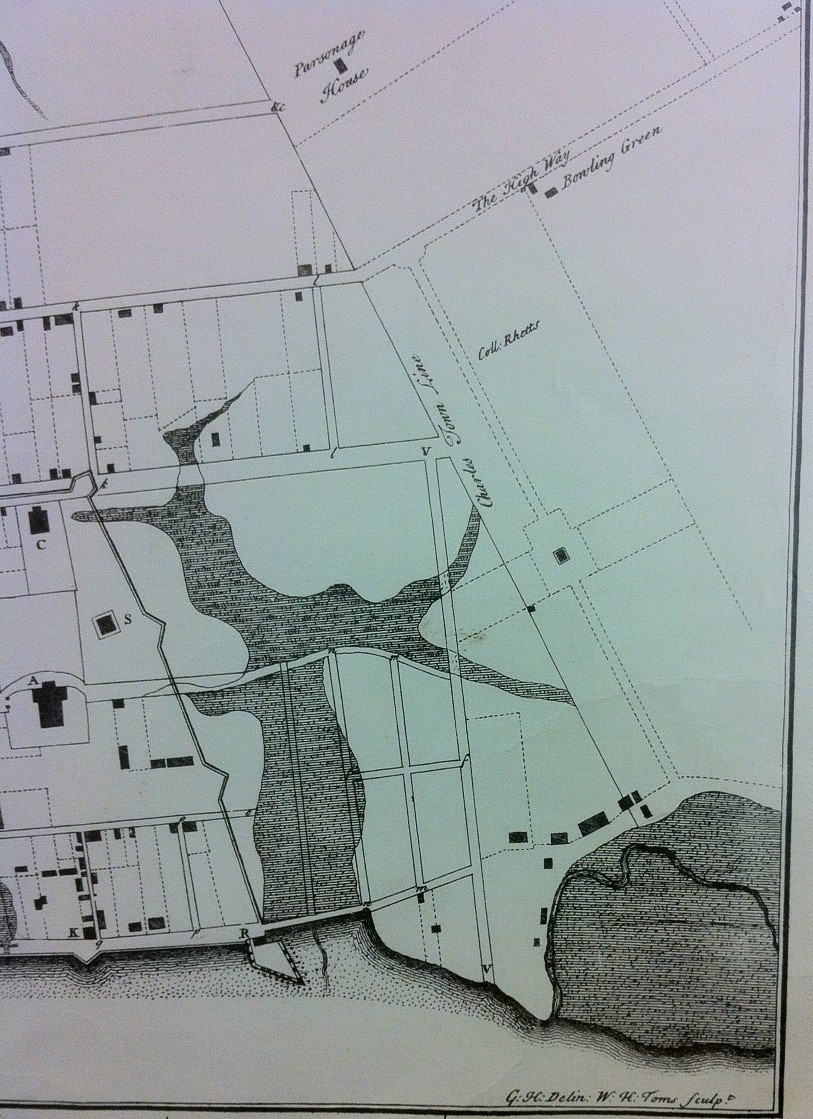

Ichnography of Charlestown, 1739, shows Col. Rhett’s lands, Bowling Green Plantation, and “the highway” (Meeting Street).

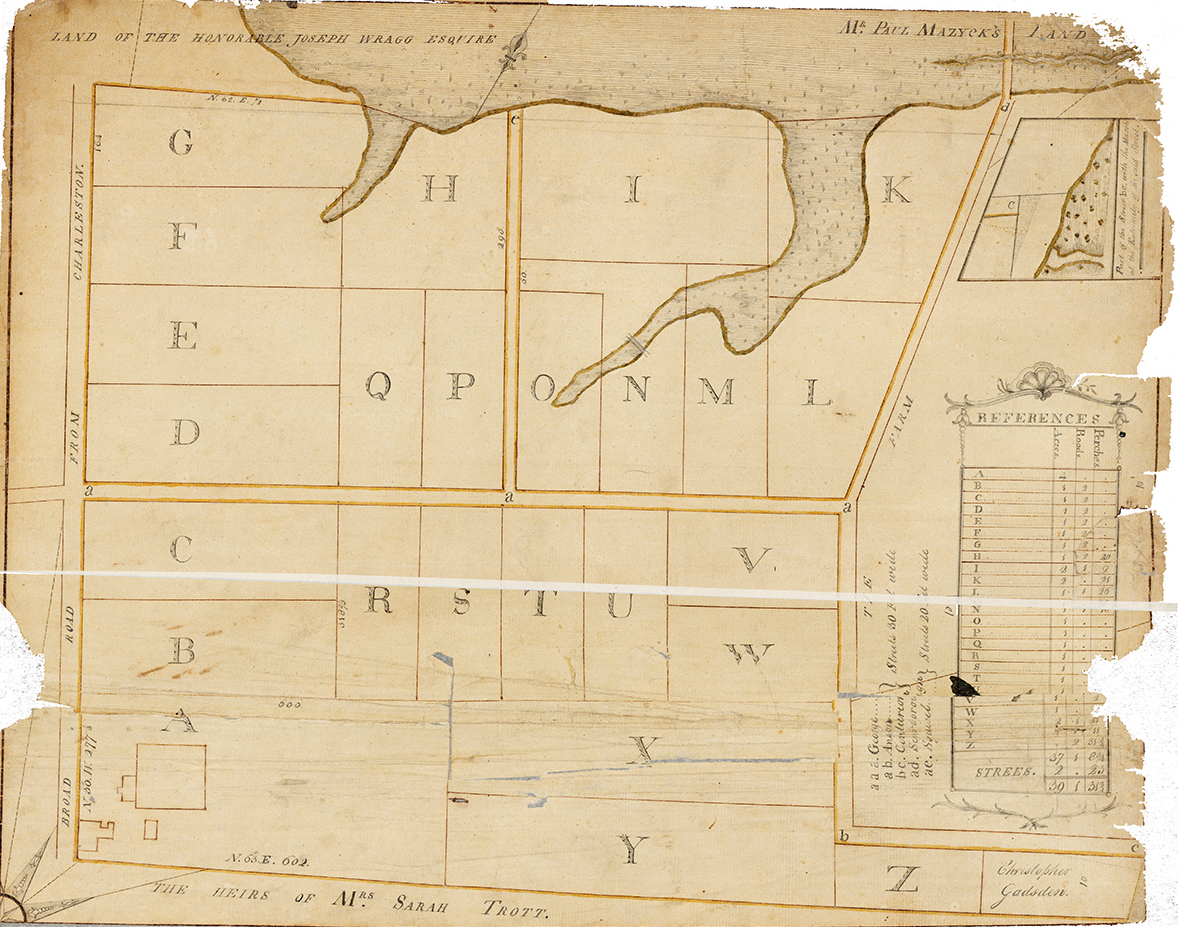

George Anson, a famous ship captain who rose to the title of Lord after circumnavigating the globe and hauling Spanish treasure back to England in 1744, is the namesake of Ansonborough. He purchased a small plantation north of Rhettsbury called Bowling Green in the 1730s, living there before returning to England, and then subdividing it to create Ansonborough. Anson and George streets are named for him, and Centurion (renamed Society) and Scarbroough (now part of Anson) were named for ships he captained. The South Carolina Society’s tract near Society Street, Rhettsbury, and Federal Green near Calhoun Street, were later absorbed into Ansonborough. Several of the large estates that faced the water along East Bay Street, including the Nathaniel Heyward house, were demolished in the early twentieth century for parking and port development, prior to preservation laws to protect them. The Gadsden House at 329 East Bay Street, recently lavishly restored as a wedding and events venue, is one of few to survive.

The circa 1712 Rhett House, Hasell Street

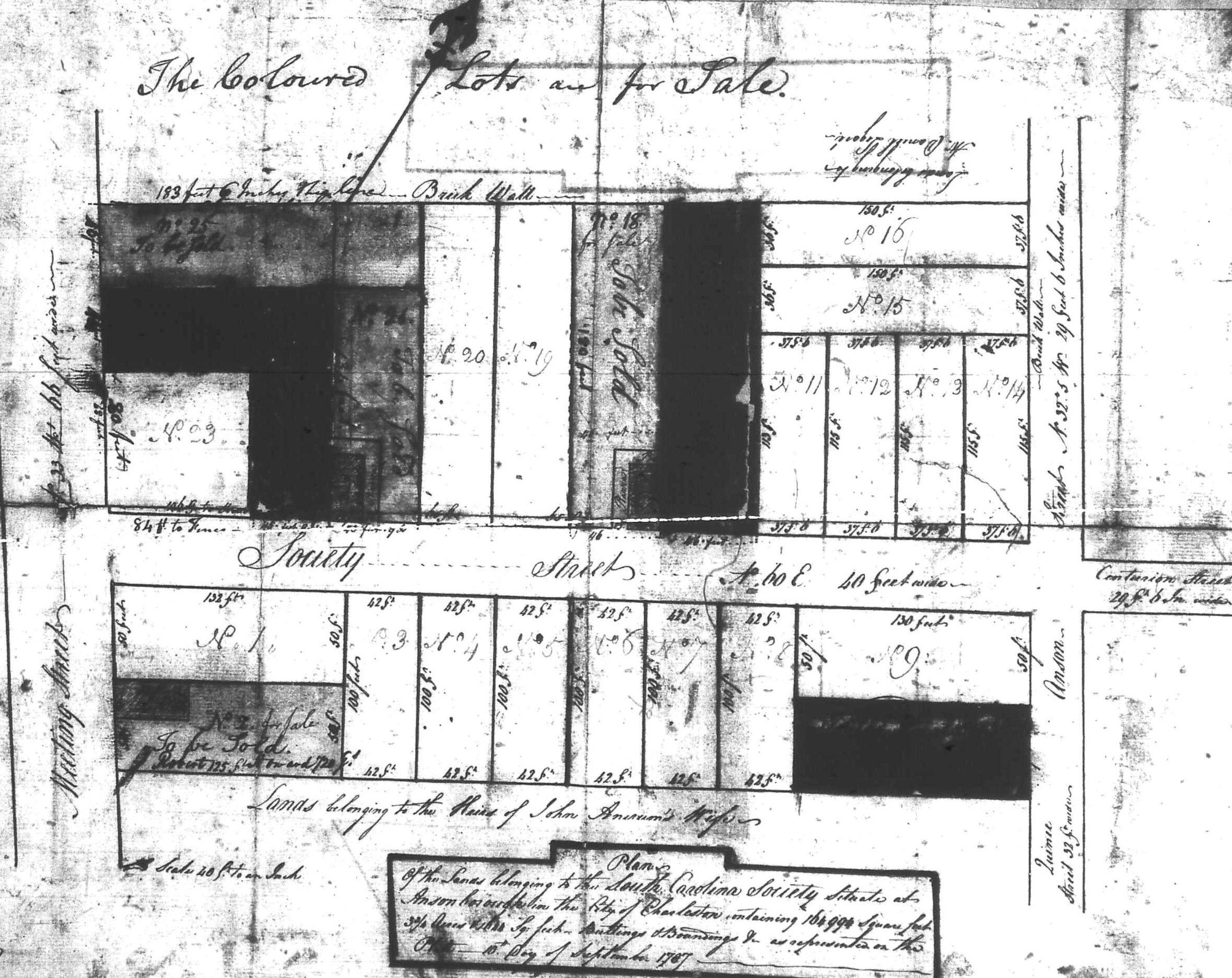

Lord George Anson, and McCrady plat 603 showing a block of Ansonbough near Society Street in 1787.

A 1740s plat of the Ansonborough subdivision, surveyed by George Hunter.

There are a few federal era houses (53 Laurens Street, circa 1815 and 75 Anson Street, circa 1800), but most of Ansonborough’s original buildings were destroyed in the great fire of 1838. The fire consumed 598 principle buildings in Ansonborough, and the Charleston Mercury reported, “Society Street is one mass of flames from East Bay to within a few doors of King Street.” In the aftermath, the city enforced strict fire prevention measures and only allowed masonry buildings within the city limits.

A Map of the fire damage, Charleston Mercury, 1838.

It is a result of the catastrophic fire that most of Ansonborough’s buildings date to the 1840s and 1850s, providing its architectural continuity. Residents erected well-proportioned brick single houses and town houses, in the Greek Revival style so popular in the antebellum era. Builders snatched up large lots, subdivided them, and built nearly identical houses using the same plan, so if one looks closely in Ansonborough, you’ll notice houses with the same roofline and footprint that have been customized over the last 170 years by later owners.

Antebellum single houses on Hasell and Wentworth Streets.

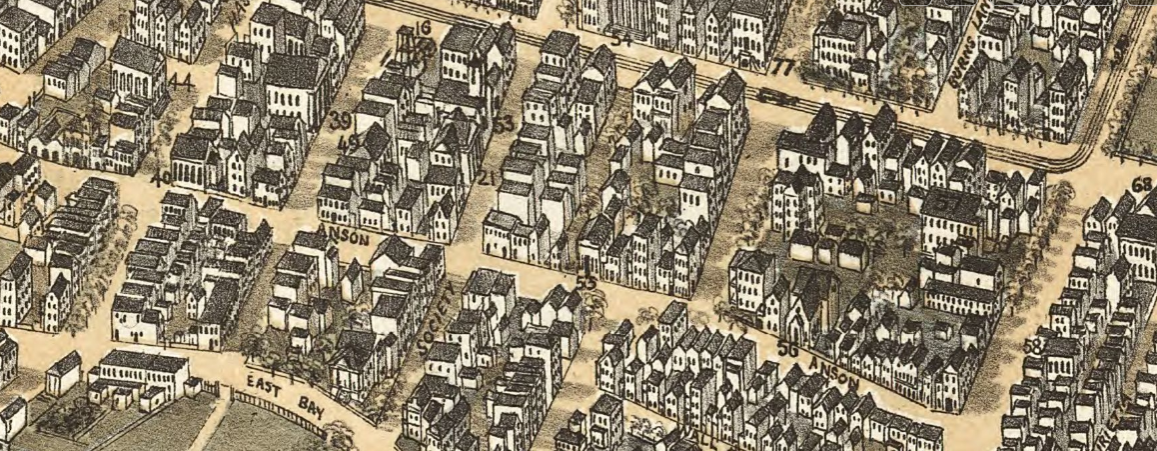

There were also small outbuildings behind the large residences, and diminutive houses near George Street that were home to enslaved residents and free people of color; in fact, in 1861, Ansonborough had a diverse population including Irish and German immigrants, with nearly one third residents of African descent. This diversity is why Ansonborough had so many churches, including St. Stephens Church (1838 building still in use, Episcopalian), St. Johannes Lutheran Church (built 1842, German congregation), St. Joseph’s Catholic (a fine Gothic Revival building constructed 1850; once an Irish congregation, now St. Johns Reformed Episcopal), St. Paul’s on Society Street (German Catholic, now a condominium), St. Peter’s on Wentworth (black Catholic, now repurposed), and Redeemer Presbyterian on Wentworth Street (originally Lutheran.)

Birds Eye View of 1872 showing the many churches in Ansonborough. 56, Irish Catholic; 53, Episcopal; 39 and 40, German Lutheran; 44, Methodist; 53 on Society, German Catholic.

It is hard to imagine such a beautiful neighborhood in a state of disrepair, but by the 1950s, most homes in Ansonborough had been converted into rental properties and tenements, many severely dilapidated even though fully occupied. During World War Two, people had flocked to the area for military and maritime work, but many of those jobs were gone after the war, and Ansonborough became impoverished. Ansonborough was not unique, as there was a widespread ‘white flight’ out of inner cities in the post-World War Two era as those who could afford it and were welcome moved to new suburban communities, while working class residents who needed to be close to their jobs (like the dock workers and laborers of Ansonborough and Gadsdenborough next door) remained in the city in increasingly depressed areas.

Unlike other neighborhoods that languished, Ansonborough became the target of the first neighborhood rehabilitation program in the nation. Historic Charleston Foundation, a preservation advocacy group founded in 1947, recognized the architectural value of Ansonborough’s antebellum homes and stepped in to change the neighborhood’s course. HCF created a revolving fund in 1957 and began buying batches of houses, partially restoring them, placing protective covenants on them and selling them to preservation minded buyers, and then taking the proceeds to purchase the next round of houses. Through their focused long term plan, the Ansonborough Rehabilitation Project, HCF renovated and restored nearly 100 houses by the 1970s.

A house tour brochure from the 1970s. Vertical file, CCPL.

75 Anson Street in 1937 as a tenement house, and today fully restored.

Ansonborough became better maintained, but the change did not occur overnight, and took civic support, private interest, and preservation community support, and led to permanent population changes. Ansonborough was restored to its former glory and became increasingly popular and expensive by the 1970s, but the area did gentrify, and most African American renters were priced out of the area. So too went the smaller buildings, businesses, and corner stores as Ansonborough became almost exclusively residential.

One of the biggest changes to Ansonborough was the construction of the Gaillard Audorium in the 1960s, which entailed demolishing hundreds of historic residences and erasing earlier streets to create the large building site. HCF purchased and moved some of the more significant buildings, relocating them to vacant lots along Anson and Laurens Street where smaller structures and businesses had previously been. The modern, controversial International Style auditorium was expanded and fully renovated in a neoclassical style in the 2010s and is now landscaped with a popular green and paths facing Calhoun Street.

A 1944 Sanborn Fire Insurance Map of the houses demolished to create the Auditorium site.

In the pioneering years of the 1960s, young preservationists flocked to Ansonborough, including the neighborhood’s most notorious residents, Dawn Langley Hall Simmons. Dawn was born in England as a man named Gordon Hall, and it was while living in Ansonborough that she became one of the first people in the United States to have a sex reassignment surgery. She then married an African American man, John Paul Simmons in 1969, a double scandal in the conservative South of that era. Simmons eventually moved to New York, and several of the early renovators moved over time as well, but was no shortage of interest from buyers looking for full time Charleston dwellings or second, seasonal homes. In the 1990s, a parcel of land tucked behind the Middleton Pinckney House, which had formerly been a reservoir and swimming pool, was filled, and a lovely planned urban development was created, with single houses and other traditional forms lining Menotti Street.

Residents in Ansonborough are in the cultural center of the city, with the Gaillard Center in their midst, where Spoleto performances take place internationally renowned musicians and authors perform year round. Theodora Park on George Street is a perfect place to read or enjoy lunch. It was created by Ansonborough resident David L. Rawle in partnership with the city and is named for his mother, an avid gardener. Across East Bay Street is the South Carolina Aquarium and Gadsdenboro Park for the more athletic minded resident. Meeting and King Street a block away are lined with popular high end restaurants, and the Harris Teeter grocery store, a favorite for locals, is on East Bay Street. With all the neighboring amenities but intact architectural character and quiet ambiance, it’s easy to see why Ansonborough remains one of the most desirable neighborhoods in the city.

Sources:

– Christina Butler. Ansonborough: From Birth to Rebirth. Charleston: Historic Charleston Foundation/HANA, 2019.

– Nicholas Butler. “Captain Anson and the Spanish Entourage.” Charleston Time Machine, CCPL, November 2017. https://www.ccpl.org/news/captain-anson-and-spanish-entourage. Accessed August 2018.

– Nicholas Butler. “Remembering Rhettsbury.” Charleston Time Machine, CCPL, February 2018. https://www.ccpl.org/news/remembering-rhettsbury. Accessed August 2018.

– Vertical files, Ansonborough, South Carolina Room at CCPL

– McCrady Plat Collection

– City Engineer’s Plats, Charleston Archive at CCPL

– Historic American Buildings Survey

– Daniel Crooks Jr. Charleston is Burning: Two Centuries of Fire and Flames. Charleston: History Press, 2009.

– Jonathan Poston. Buildings of Charleston. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

– Robert Wyeneth. Historic Preservation for a Living City: Historic Charleston Foundation 1947-1997. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

– Historic Charleston Foundation, “About us”, http://www.historiccharleston.org/about/