Folly Beach: The Edge of America

By Christina R. Butler/Butler Preservation for

Charleston Empire Properties – 10 May 2020

Folly Beach is a small community located just eleven miles from historic Charleston on a sea island perched on the Atlantic Ocean. Today Folly is a continuous, narrow island southeast of James Island, and stretching from the Stono River inlet to Lighthouse inlet on the east end. It’s early history includes legends of shipwrecks, important Civil War heritage, ties to the famous opera Porgy and Bess, and locals’ memories of learning to drive on the beach in the 1940s. While attracting nearly a million visitors a year, Folly retains its kitsch character and iconic American surfer vibes. Besides beautiful beachfronts, a popular boardwalk, and adjacent seafood restaurants and local bars, Folly boasts varied residential architecture ranging from beautiful beach front custom homes, to small mid-century cottages with porches and historic character.

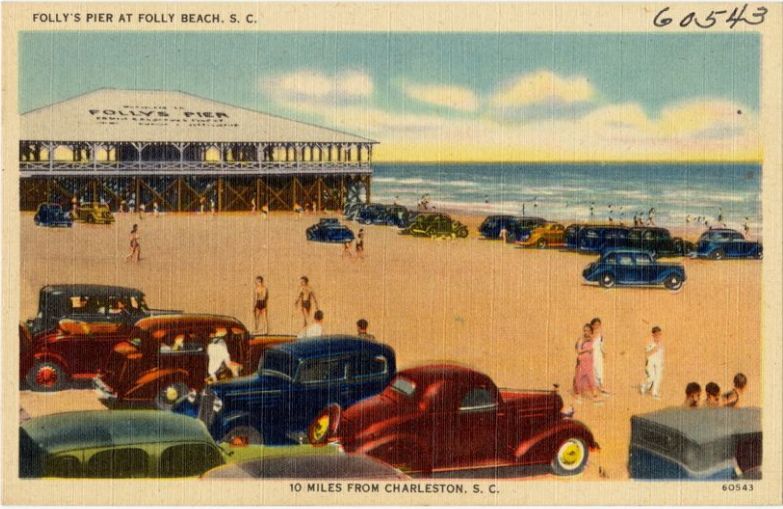

Folly’s Pier at Folly Beach in the late 1930s. Boston Public Library.

Folly Island was originally granted to the Rivers family, but remained undeveloped and mostly natural well into the nineteenth century. It was home to the Bohicket Native American tribe prior to European settlement. By 1731, a 350 acre portion of the island had passed to the Stanyarnes, who like the Rivers’, owned extensive sea island acreage. As a sandy sea island, it was not cultivated extensively like nearby areas that were converted into plantations early on. The coastline is constantly evolving, and historic records sometimes refer to the area as two separate islands, Little and Big Folly. It was also called Coffin Island on some early maps; there are several theories about the origin of that name, including Folly’s proximity to historic ship quarantine areas. For example, in 1832, the Brig Amelia, which had a cholera outbreak on board, wrecked just off Folly Island.

Folly Island on the 1825 Mills Atlas, Charleston District. Note “Coffin Land” and lighthouse to the east.

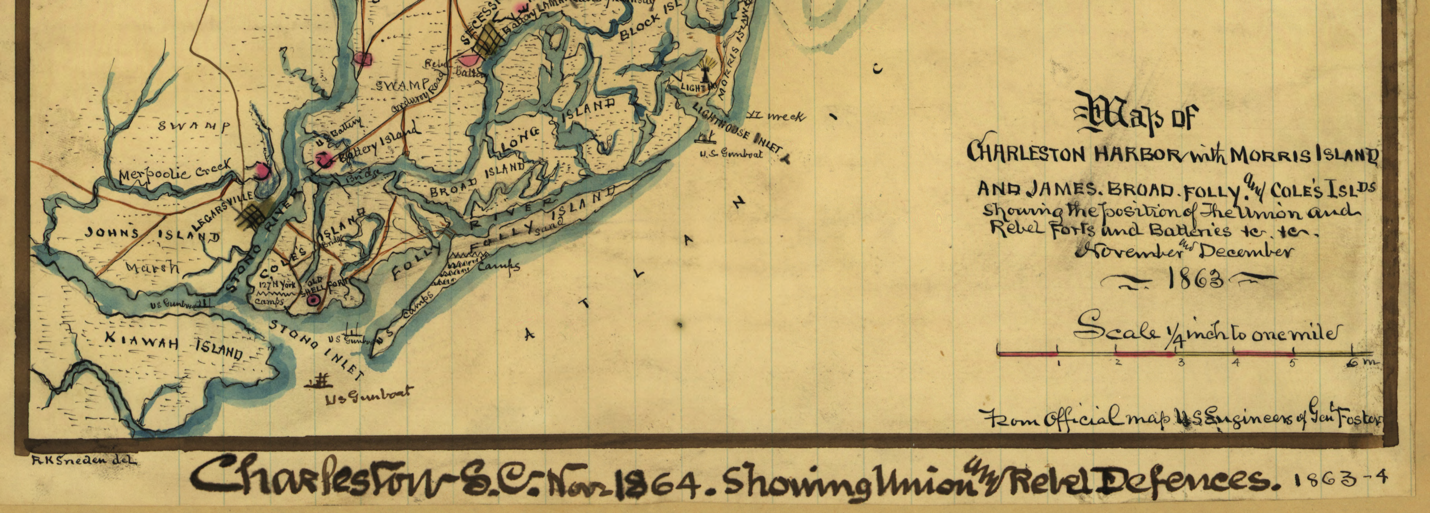

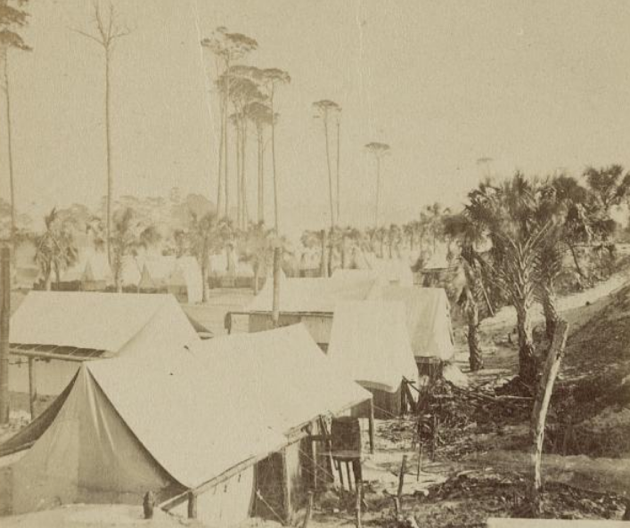

Folly saw little activity until 1863, when Stratton Lawrence noted that, “the first roads on Folly Island were cut by Union troops who camped there during the Civil War.” Nearly 13,000 northern soldiers used the island as a base in the fight to take Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor. There are National Register documented sites at the western end of the island, where batteries were located and where several members of the famous African American 55th Massachusetts regiment are buried. The 54th and 55th fought a bloody campaign on Folly and Morris islands against the Confederacy, and were later made famous in the film Glory. After the war, the island “returned to obscurity for half a century”, with occasional visitors arriving by boat and camping in tents.

“Map of Charleston Harbor”, 1863 showing Folly and surrounding islands. Library of Congress.

Union encampment, and the remains of a blockade runner in 1865 on Folly. Library of Congress.

In 1919, Folly Island Company purchased the island, with an eye to turning Folly into a vacation destination. They received state permission to build a bridge across folly Creek and River to link Folly to James Island. Folly Road (running across James Island) was improved and the first beach front pavilion and cottages were built. The most famous guest in the early days was George Gershwin, who stayed on Folly with Charleston author Dubose Heyward in 1934 to work on his musical adaptation of Porgy, which became the famous American opera, Porgy and Bess.

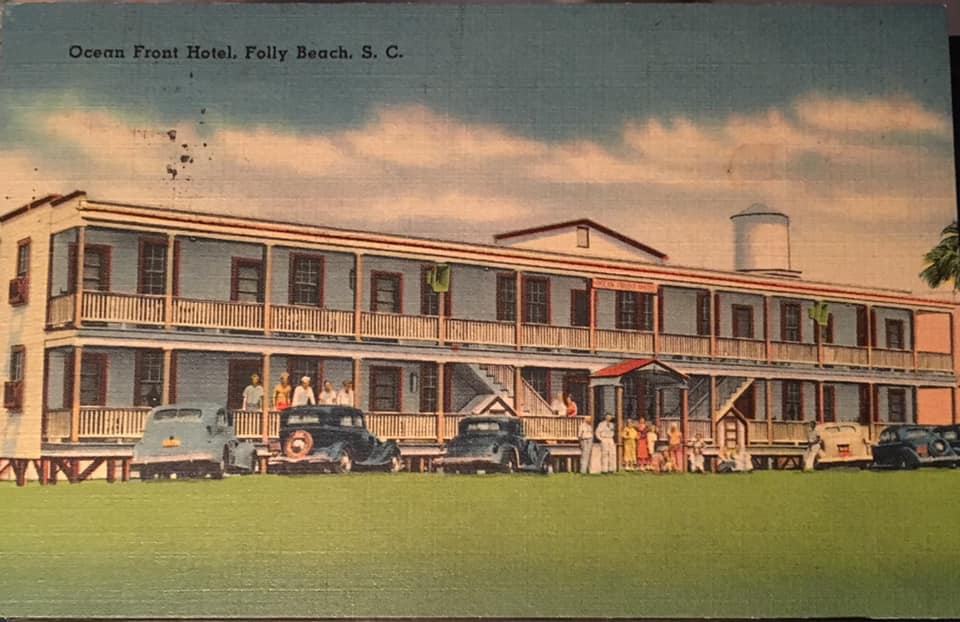

Folly Beach took off as a popular resort community in the 1930s, beginning with the development of Folly’s Pier in 1931. Restaurants and stores cropped up for seasonal local residents and vacationing tourists. Oceanfront Hotel became the first large facility to cater to overnight guests, in 1934.

Oceanfront Hotel in the late 1930s. Boston Public Library, Tichnor Brothers Collection.

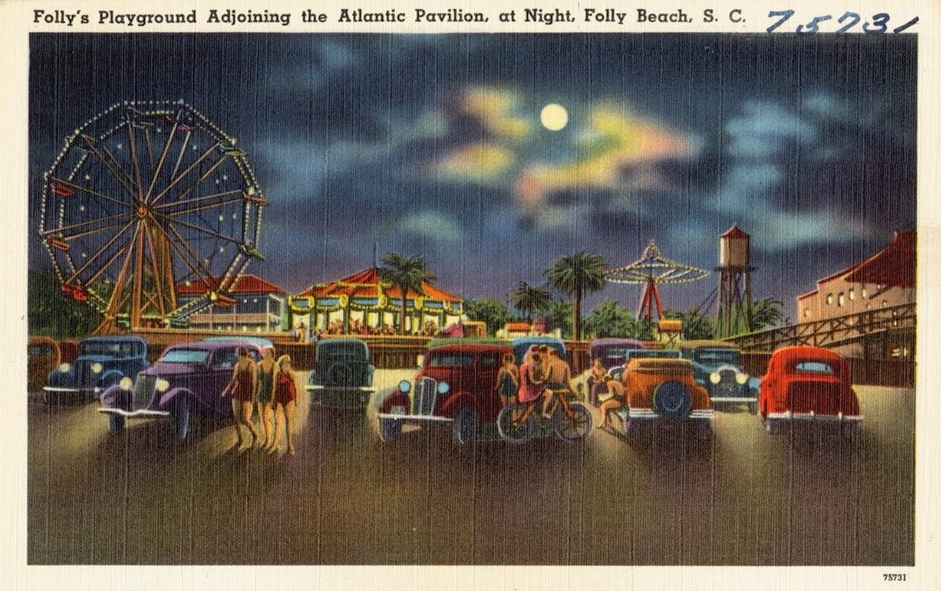

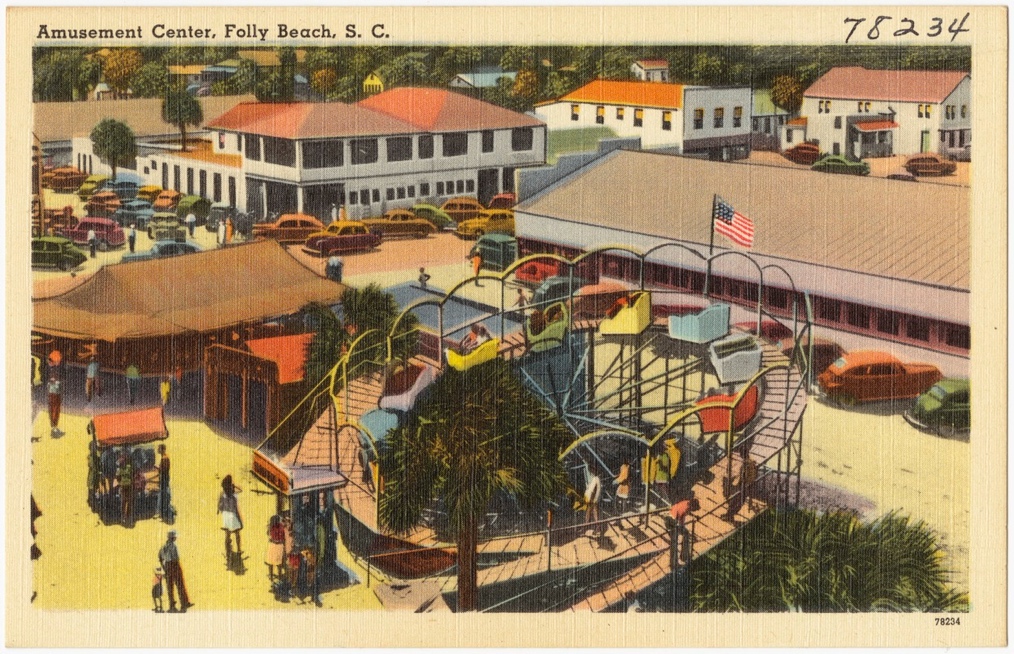

Based on postcards, visitor’s memories, and advertisements of the era, Folly was the quintessential beach community right of a Hollywood movie of the 1950s and 1960s. The island’s businesses and entertainment included several ice cream shops and restaurants, a skating rink, and even an amusement park with merry go round, flying chairs, and a Ferris Wheel. An icon of Folly that sadly has been lost is the Atlantic Boardwalk and Pavilion, where guests danced to live orchestras along the oceanfront and visited the bathing house and soda fountain in the 1930s.

Atlantic Pavilion by moonlight, with the Ferris Wheel illuminated in the background. Boston Library.

The amusement park at Folly Beach. Boston Library.

Folly Beach circular from 1949, News and Courier

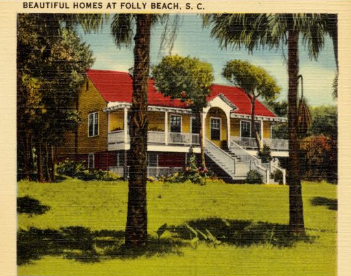

During the mid-twentieth century boom, residents and investors alike built wood frame cottages and cinder block houses with front porches to catch the sea breezes, in short walking distance from beach entertainment.

Ads from 1933 and 1920 for new lots in Wagener Terrace and Riverside (Tristram Hyde was a former mayor of Charleston.)

1940s postcard of a beach house on Folly. Boston Public Library.

Folly experienced a short decline in the late 1960s, when fewer acts came to the pavilions, erosion caused beach damage, and cars were banned from the beach. In this era, the amusement rides also disappeared, but within two decades, a new burst of development and interest hit Folly. Folly Pier burned in 1957 and 1977, and was eventually replaced in 1995 with the expansive Taylor Pier, stretching 1,045 into the ocean and creating a popular fishing and gathering spo.t The Tides hotel, constructed in 1985 and recently renovated, is one of few larger hotels, but many guests rent beach houses for a more local feel. Center Street still features surf and souvenir shops, bars, and seafood restaurants in 1960s storefronts.

Taylor Pier and Folly Beach today. Library of Congress.

Shops and restaurants on Center Street leading to Folly Beach.

Hurricane Hugo in 1989 damaged over 100 houses, leaving room for the construction of beautiful new beach houses with large ocean front piazzas, some of which are on the market today. The hurricane’s erosion damage also created the Washout, a popular surfing spot. Hugo did bring a new addition to the island- the famous Folly Boat, which was washed ashore in the storm and marks entry onto the island, and is a brightly painted canvas of ever changing street art.

A recently sold home on West Ashley Street and the view from another house recently on the market will entice beach lovers.

Folly today is an incorporated city with 2400 residents, but it remains known for its lay back and authentic attitude, compared to more exclusive recent beachfront communities; it is often the preferred beach for locals, some of whom still have their summer cottages on the island. Potential buyers have their choice of mid-century or brand new houses, a short drive from downtown Charleston and the neighboring sea islands, and just a stone’s throw from the Edge of America, Folly Beach.

View of the beach.

Sources:

– – Library of Congress maps and photo collections

– Stratton Lawrence. Images of America: Folly Beach. Charleston: Arcadia Press, 2013

– Massachusetts Digital Commonwealth, Tichnor Brothers postcard collection

– College of Charleston. “An Educator’s Guide to Folly Island.” http://oceanica.cofc.edu/An%20Educator%27sl%20Guide%20to%20Folly%20Beach/guide/FBHistory.htm

– South Carolina Department of Archives and History, online archives index

– Gretchen Stringer-Robinson. Time and Tide on Folly Beach, South Carolina. Charleston: Reprint, 1998.

– William James Hagy. The Edge of America: Folly Beach, A Pictorial History. Charleston: Shaftsbury Books, 1997

– Leigh Handal. Lost Charleston. London: Pavilion Books, 2019.