At Home in Harleston: Charleston’s pre-Revolutionary Suburb

By Christina R. Butler/Butler Preservation for

Charleston Empire Properties – 28 March 2020

Harleston Village is one of Charleston’s largest neighborhoods and is home to a diverse range of historic houses placed on large lots along wide, tree-lined streets running between Calhoun and Broad Streets. Harleston’s boundaries have changed over time and have grown as residents filled the creeks and marshes of the Ashley River, which acts as the western boundary of the neighborhood, along with Lockwood Boulevard.

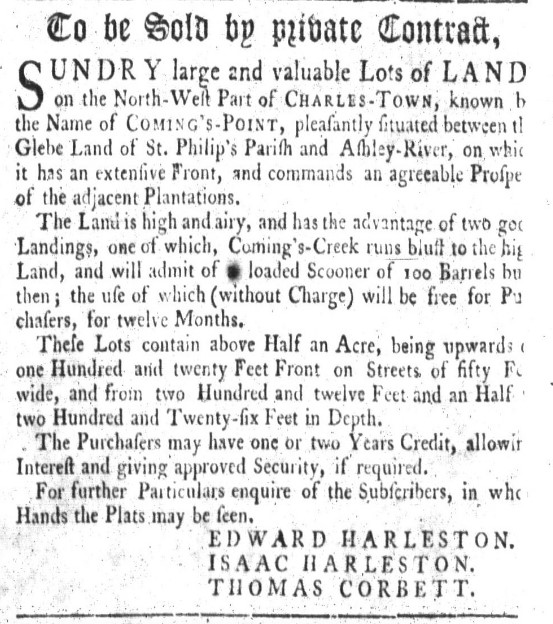

John Coming and Henry Hughes received grants for over 319 acres of the land in 1671 in Harleston Village in Charleston, SC, and it later passed to the Harleston family through marriage (Affra Harleston married John Coming, and she donated a parcel of land to the Anglican Church to generate rental income — the origin of Glebe Street). The Harleston real estate & history was rural pasture lands and marshes owned by the Coming and Harleston families in the colonial era and was outside of town; in 1750, Elizabeth Harleston advertised part of the land for rent as a “a convenient pasture (for either a butcher or inn-keeper),” and apparently she did not have a house in the still undeveloped area.

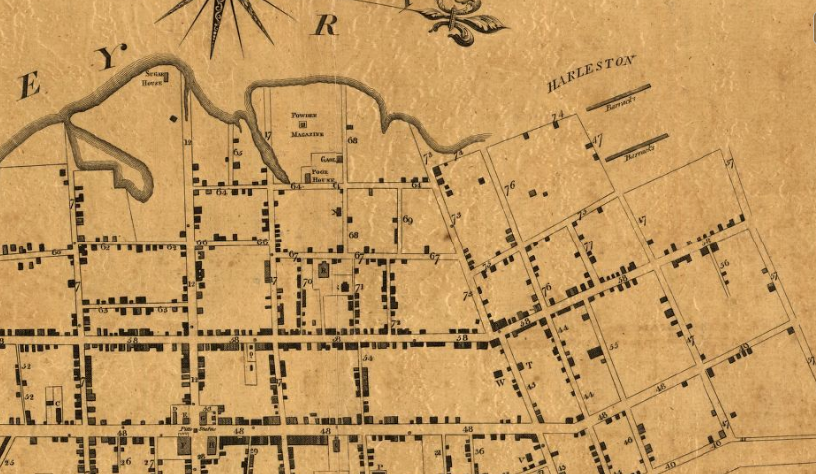

After Elizabeth’s death, her sons John, Nicholas, and Edward inherited the property and petitioned the colonial government in 1767 to extend existing roads towards their tract so they might develop it. Harleston was created in earnest in 1770 as a suburban speculative development as the brothers created 162 large lots along several principal streets adjacent to the earlier settled area of Charleston. At that time, Beaufain Street was the neighborhood’s southern boundary, and Coming’s Creek cut inward several blocks from the Ashley River. Most of the lots in the Harleston Village in Charleston, SC have since been divided into smaller parcels, and the neighborhood has grown and expanded westward.

A copy of the Harleston subdivision plat from 1770, showing the original streets, lots, and topography.

Historian Nic Butler notes that many of the streets in Harleston real estate & history (originally called Coming’s Point) were named for important South Carolinians, early patriots, and supporters of the American cause in the Revolutionary War. For example, Bull Street is named for Lt. Governor William Bull Jr. (1710-1791); Beaufain Street is named for Collector of Customs for the Port of Charleston, Hector Berringer de Beaufain (1697-1766); Montagu Street was named for South Carolina Governor Charles Greville Montagu (1741–1784); Pitt Street was named for William Pitt “the elder” (1708–1778), a British politician known for his support of the Americans during the Stamp Act Crisis; and Rutledge Avenue was named for John Rutledge, a member of the Stamp Act Congress in New York, and later, a governor of South Carolina. Butler also notes that Harleston was never a separate village, but acquired the name “Harleston Village” around 1970 when the area became a National Register.

South Carolina Gazette sale advertisement, 3 May 1770.

The Ichnography of Charleston shows Harleston as it appeared in 1788. “12” is Broad Street, “72” is Beaufain Street, and “57” is Manigault (Calhoun) Street. The “barracks” is now College of Charleston and “Powder Magazine” is the location of the Old Jail.

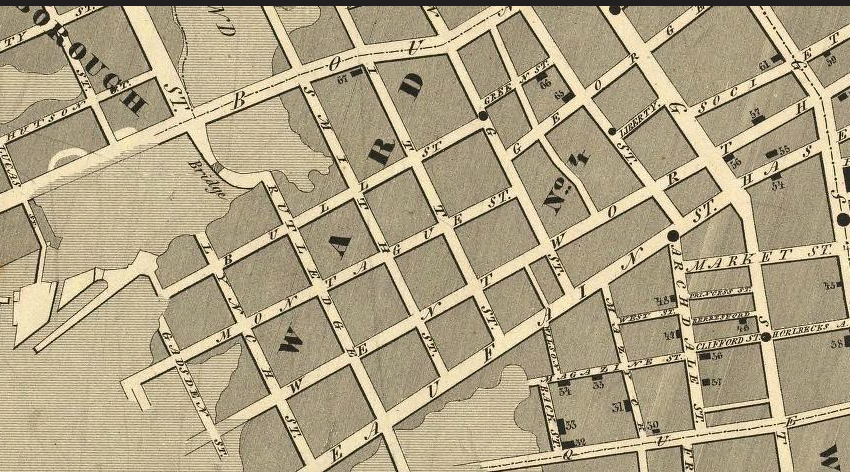

Harleston real estate & history grew in the nineteenth century to include Wragg’s pasture (bounded by Calhoun, King, and St. Philips streets) and the Mazyck lands (in the vicinity of Logan Street). The Ashley River marshes originally fed inland as far as Franklin and Smith Streets, but today they are several blocks further to the west. Thomas Bennett and Daniel Cannon owned lumber and rice mills near the river (the West Point Rice Mill, which is now a wedding and event venue, is one of the few surviving examples) but as the city grew, the ponds were filled and the causeways turned into proper roads.

McCrady plat 1199 from 1794 shows the extensive marshes and creek near Bull and Calhoun Streets.

a map of Charleston from 1844 shows the slow growth along the western edge of Harleston.

Harleston real estate & history boasts nearly every architectural style popular in the past 250 years, from the Georgian character of the Philip Porcher house (built in 1773), to Federal style brick Charleston single houses, to Greek Revival side hall houses, to a beautiful array of Victorian houses of various sizes and materials. Some of the earliest dwellings are found in the glebe lands. There are smaller wood frame single houses on the courts near Colonial Lake such as Short and Trumbo streets, while closer to the Ashley River lie later buildings on made land, including townhouses along Lockwood Drive from the late twentieth century. Harleston Village in Charleston, SC is home to the second largest house in Charleston, the circa 1886 Wentworth Mansion, now a popular hotel with a restaurant in the former carriage house. The stately Second Empire-style house features a cupola that offers some of the best views of the city’s skyline.

The Porcher House (1773) and the Wentworth Mansion (1886)

Mid nineteenth century eclecticism in Harleston.

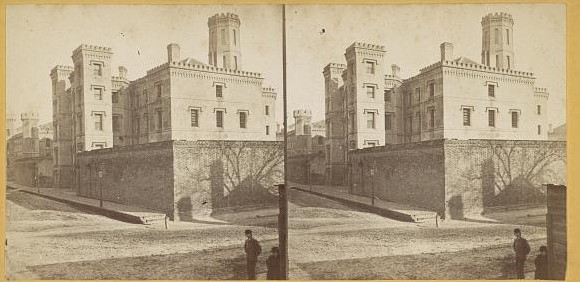

Harleston is also home to (allegedly) the most haunted building in the city- the Old District Jail on Magazine Street, constructed in 1802 in a foreboding institutional Gothic style. The large brick building is now used for ghost tours and awaits full renovation and adaptive use. Even before the jail was constructed, the area had a dark past; part of the 34 acre tract granted to John Moore in 1698 where Logan Street is today was used as a burial ground during the American Revolution and as a pauper’s cemetery, before the Jail, a workhouse, a marine hospital (still standing) and hospital were built next to one another.

The Old Jail circa 1880. Library of Congress.

Although primarily residential, Harleston Village has a college, parks, churches, a few restaurants, and other amenities in its midst. Allegedly, the first game of golf played in America took place on Harleston Green, on a pasture near Pitt and Bull Streets, in the 1740s. Harleston Village boasts one of the most popular parks in the city, Colonial Lake, which was first set aside as a public common in 1768 but then became an industrial area of mill ponds and lumber yards along the marshes. The largest pond was transformed into Colonial Lake in 1881, replete with strolling paths and plantings on each side.

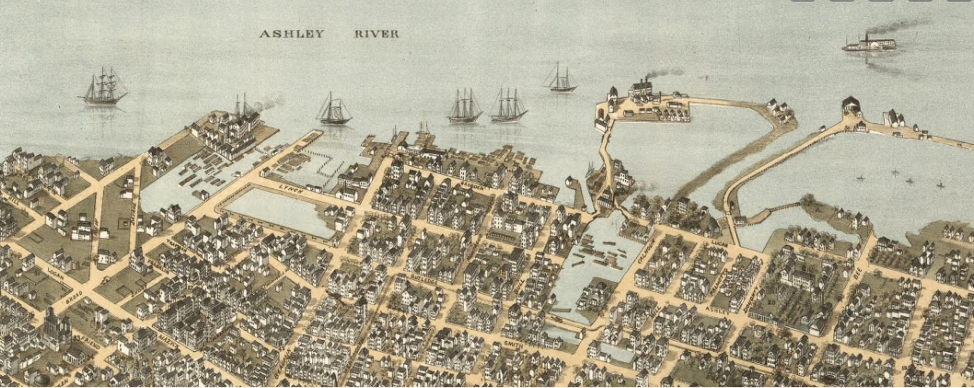

The Bird’s Eye View of Charleston, 1872, shows the growth of Harleston. The square pond to the left became Colonial Lake, and the large pond on the right is near Cannon Park at Calhoun Street today.

Colonial Lake’s promenade and surrounding residential architecture.

Near Calhoun Street is Cannon Park, which once housed the original Charleston Museum building. After a catastrophic fire, all that remains of the museum are the stately columns on the edge of the park. Neighborhood landmarks include the College of Charleston campus, a National Register district with its historic walled courtyard, Randolph Hall (originally classrooms and faculty offices), Towell Library, and a porter’s lodge. College of Charleston is the oldest municipal college in the nation (conceptualized in 1770) and is today a state institution attracting students from across U.S.

Randolph Hall, on College of Charleston’s historic campus.

Harleston residents have their pick of pass-times, from walking the neighborhood to enjoy the architecture and popping over to King Street for dinner, to strolling in the parks, crossing Lockwood Boulevard to visit the City Marina and walking along the Ashley River. With its architectural diversity and range of sizes and styles, there’s sure to be a historic property perfect for every buyer.

Ready to find your dream home in Harleston Village? Contact us today to explore available listings and learn more about living in one of Charleston’s most charming and historic neighborhoods!

– Burton, Milby. Streets of Charleston. Charleston: Charleston Museum, 1970.

– Butler, Christina. Lowcountry At High Tide *

– Butler, Nicholas. “The Genesis of Harleston Neighborhood.” Charleston Time Machine, https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/genesis-harleston-neighborhood-1672-1770

– Deeds and subdivision plats, Charleston County Register of Deeds

– Halsey Map, Preservation Society of Charleston, www.halseymap.com

– McCrady Plat Series, Charleston County Register of Deeds

– Petrie, Edmund, Adam Tunno, and Phoenix Fire-Company Of London. Ichnography of Charleston, South-Carolina: at the request of Adam Tunno, Esq., for the use of the Phœnix Fire-Company of London, taken from actual survey, 2d August. [London: E. Petrie, 1790] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/80692362/.

– Poston, Jonathan. Buildings of Charleston. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

– Vertical File, “Neighborhoods- Harleston.” South Carolina Room, Charleston County Public Library.