To find culture, art, history, and more, look no further than Charleston’s many museums. The city boasts numerous museums with various themes, and there’s something for every age group and interest and ideal for visitors looking for an orientation to the region’s culture as well as for locals wanting to learn more about their city. Charleston’s museums are a great rainy-day activity- or a perfect hot weather one, to enjoy the crisp air-conditioned spaces while learning about the Lowcountry’s past.

Tip: Some Non-profit entities own several sites, and you can save by booking a multi-site ticket (like Historic Charleston Foundation’s house museums, or Charleston Museum and its houses). There are also a few free niche museums off the beaten path, described below. Some sites offer discounted tickets for local residents on certain dates, so be sure to check their websites ahead of your visit. Most of the sites are open seven days a week, but many have short hours on Sundays to be sure to plan accordingly.

Several of the city’s best attractions are conveniently located along Meeting Street, a principal north-south thoroughfare with several parking garages nearby and wide, walkable sidewalks. Charleston’s Museum Mile https://www.charlestonsmuseummile.org “features the richest collection of cultural sites open to visitors in downtown Charleston.” The one-mile stretch includes six museums, several house museums, four parks, and several public buildings and churches along the way. As we cover the city’s sites below, look for a “CM” for museums along the mile.

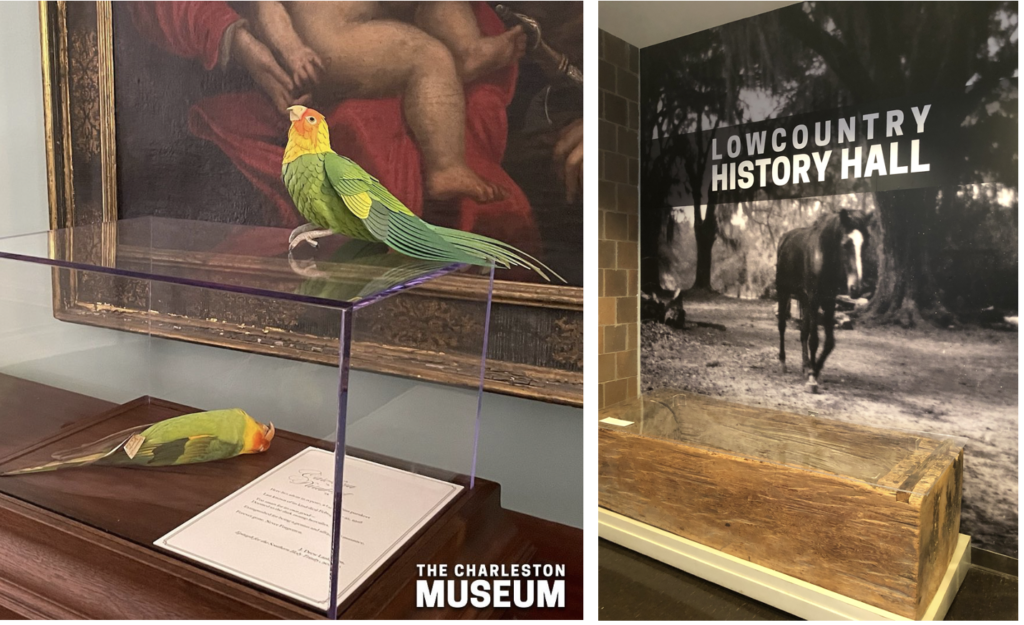

Founded in 1773, Charleston Museum is often considered to be “America’s First Museum”. https://www.charlestonmuseum.org

The Museum as an illustrious history: “inspired in part by the creation of the British Museum, the Museum was established by the Charleston Library Society on the eve of the American Revolution and its early history was characterized by association with distinguished South Carolinians and scientific figures including Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, Thomas Heyward, Jr. [whose house is now open as a museum], Reverend John Bachman and John J. Audubon.” The Museum’s diverse collections include a large natural history wing, the Lowcountry History Hall (which is chock-full of well curated artifacts because the Museum’s archeologists are some of the most active in the city), photograph exhibits, Charleston silver and textiles, a vintage coach, historic signage, and a regularly changing special exhibit space.

360 Meeting Street. Three-site ticket (Museum, Manigault House, and Heyward Washington House): $25.

The Mace Brown Natural History Museum, located in College of Charleston’s Math and Science Building at 207 Calhoun Street and open for free (donations go to the Paleontology Club), is another great stop for fossil lovers; “the Department of Geology and Environmental Geosciences is home to a Paleontology Museum that displays almost 1,000 fossils. The displays include dinosaur bones, crinoids, Oligocene mammals of North America, mosasaurs, cave bears, Pleistocene mammals of the Carolinas, ocean life through time and fossil plants. A favorite exhibit for many is the reconstructed jaw which houses real teeth from the giant extinct shark Megalodon.”

Located in a grant turn of the century Beaux Arts style building replete with a stained-glass dome in the upper gallery, the Gibbes Museum of Art is a must-see. The Gibbes an important cultural institution dating back to 1905. Their collections include a spectacular array of Lowcountry-made art and material culture spanning four centuries to the present, including beautiful antique Charleston build period furniture, portraits of historic elites, landscape painting, over 600 portrait miniatures painted on ivory (several by Samuel Morse, an artist more famous for inventing Morse code), and changing exhibits. There is a sculpture garden in the rear, and extra space with class rooms for workshops and seating for special events and lectures.

Location: 135 Meeting Street. $12 for adults. https://www.gibbesmuseum.org

The relatively new South Carolina Historical Society Museum is located along a cobblestone street next to Washington Park and is houses in the grand Roman Revival Fireproof Building, designed by nationally renowned architect Robert Mills in the 1820s. The building was designed as a records repository in the days before electricity, so Mills planned it with a skylight to reduce the use of flammable lighting sources, and with solid masonry walls and metal shutters. The galleries focus on the diverse and complex history of the state, and include plantation artifacts, maps and natural prints, “celebrating diversity”, “Africa to America”, and a gallery devote to Charleston’s natural disasters, wars, and recovery.

$12 for adults.

The Children’s Museum is a great way for the young ones to blow of steam while learning from the STEM oriented hands-on exhibits. There is an Art Room, a Speak Loud space where kids can sing and experiment with being part of a theater show, a Pirate Ship, Kid’s Garden, toddlers’ area, and more.

25 Ann Street; $15 admission; memberships available. https://explorecml.org

The Powder Magazine on Cumberland Street was constructed in 1713 to house gun powder, and is the oldest public building in the state. The Magazine has three-foot-thick walls and a complicate pantile roof with a sand lining, designed to lessen the impact if an explosion occurred (which fortunately never happened). The Magazine was located on the edge of the colonial walled city of Charleston, and a detailed diorama inside shows visitors what the city looked like before 250 years of growth. The exhibits in the small but well curate museum focus on the military history of early South Carolina, and the colonial era of Charleston. The gift shop was custom designed to replicate a historically accurate 18th century shop space. Kids love the magazine, and investigating the historic cannons on site. If you’re lucky, you might be in attendance during a special event where a small replica cannon is packed with powder and fired!

79 Cumberland Street. Adults, $6; children, $4. https://www.powdermagazine.org

At the foot of Broad Street at East Bay lies the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon, another site that’s ideal for history lovers of all ages. The circa 1771 building was the last in the city to be built with British funding, and during the Revolution as politics and loyalties changed, the basement was used as a dungeon to house Patriot prisoners during the British occupation of Charleston in 1780 (it’s allegedly one of the most haunted buildings in Charleston). The main floor has meeting and exhibit space dedicated to the colonial history of the city and the war. The steps leading to the top floor are lines with historic photographs of Charleston in the past, showing her resiliency after the Civil War and the Earthquake of 1886. The top floor is a grand ball room with exhibit space in the adjoining rooms. Now a popular wedding venue, the room hosted none other than George Washington on his 1791 southern tour, and he dances with hundreds of Charleston ladies in the space. The building is a National Historic Landmark; “over the last two and a half centuries, the building has been a commercial exchange, custom house, post office, city hall, military headquarters, and museum. Previously the property of the British, United States, Confederate, and Charleston city governments, the Old Exchange Building is today owned by the South Carolina State Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution and operated by the City of Charleston.”

122 East Bay Street. Adults, $15; Children 6-12, $8; children under 6, free. https://www.oldexchange.org

Next the Old Exchange, a historical marker explains that before emancipation, enslaved people were sold at auction on the site. Slavery is a difficult but important aspect of the Charleston’s past, as enslaved people were the majority of the population and helped build the city and held nearly every type of job to keep it running in the past. The Old Slave Mart Museum just a block away on Chalmers Street is the best place to learn more about Charleston’s enslaved people. “The Old Slave Mart Museum is the first African-American slave museum. It is often staffed by individuals who trace their history to the enslaved people of Charleston. At one point during slavery, as many as 35-40% of enslaved people entered the United States through Charleston,” and the collection includes difficult but poignant artifacts and images from the era of slavery. The building itself was constructed by Thomas Ryan in 1859 as a slave auction house, and is likely the last surviving slave auction gallery in the state.

6 Chalmers Street. $12 for adults, $5 for children 7-17; under 7, free. https://oldslavemartmuseum.com

Lovers of architecture, fine furnishings, and material culture will enjoy the city’s many house museums, each telling the unique stories of the eras and occupants from whence they date. House museums are a great way to step back in time and picture what is was like to live in Charleston, and each site has expert guides to share the past with guests.

Aiken Rhett House was built circa 1820 in the fashionable new suburb of Wraggborough, and was remodeled in the Greek Revival style in the 1830s and expanded again in the 1850s. Visitors experience the Aiken’s private art gallery, where they displayed their purchases from the grand tour, and can meander at their leisure to a self-guided audio tour through the bottom three floors of the house, and out into the grounds. Aiken Rhett has one of the most intact complexes of outbuildings in the city, with housing for the enslaved who operate the home, a laundry replete with an archeological exhibit, privies, a Magnolia tree allee, and a Gothic Revival carriage house and stable. The house is in a preserved state, so don’t expect to see restored furniture and freshly painted surfaces. Guests describe this house as frozen in time, and you can see all the layers of change to the house over time.

Also operated by Historic Charleston Foundation is the Nathaniel Russell House at 51 Meeting Street, built in 1808 by a wealthy Rhode Island merchant who settled in the city. The house is fully restored to its federal era splendor and has period furnishing and finishes throughout. Russell operated an office in the front of the house, while beyond fine glazed doors lies the grand spaces where the family entertained. The house has a three-story free flying spiral staircase custom constructed with traditional joinery, and oval shaped dining and music rooms with intricate plasterwork that was faux painted and hand gilded. The rear buildings house exhibit space and artifacts. The large garden is open for free to the public. https://www.historiccharleston.org

The Edmondston Alston House is one of the earliest houses constructed on the famous High Battery, and it commands a view of the harbor and Fort Sumter. Residents at the house witnessed the first shots of the American Civil War in April 1861, from the drawing room that guests visit today. The house was built in 1825 and later updated in the Greek Revival style, when the grand columns were added to the three story piazza, the interior plasterwork was updated, and the lacy cast iron balcony was added to the front of the house. Edmondston Alston is furnished with antiques to reflect antebellum tastes.

21 East Battery Street. Adults, $15, Students, $10; children 6-13, $5. Tip: Book a combo ticket and visit Middleton Plantation on the Ashley River to experience historic city and country living. https://www.middletonplace.org

The Joseph Manigault House at 350 Meeting Street next to the Charleston Museum (and operated by them) was built in 1801 by Gabriel Manigault, the namesake’s brother and a well known “gentleman architect”. The imposing Adam style brick house has curved balconies overlooking a fine suburban garden replete with a bell roofed garden house. The Manigault House is important in Charleston’s preservation movement: Standard Oil planned to demolish the house for a gas station, but preservationists saved it and opened it as a house museum. The garden was lost for a filling station, and restored later to its former glory. The house has high ceilings, period furnishings, grand mantels and plasterwork, and a surviving small winding stair tucked behind a door, used by the enslaved people who waited on the Manigault family in the past.

The Heyward Washington House (another Charleston Museum property) at 87 Church Street is the best chance to see a grand, colonial era house. The National Historic Landmark was built in 1772 by Thomas Heyward Jr., a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a Patriot hero. The city rented the house for George Washington to reside in during his southern tour. The Grimke family lived there, and it later became a bakery on part of the ground floor. The Museum purchased and restored the house to its eighteenth century appearance in 1929. Visitors have a guided tour of the first two floors of the house, with a grand ballroom and the priceless Holmes bookcase, made in Charleston in 1740s, and then are welcomed to visit the back garden and outbuildings, including the kitchen house and slave dwellings and a stable building.

The Karpeles Manuscript Museum at 68 Spring Street is a hidden gem, and open to the public for free Monday through Friday from 10 to 3pm. The Karpeles is one of fourteen museums throughout the US that were created from a bequest by David and Marsha Karpeles to showcase their eclectic private collection and share their nearly 1 million-item inventory with the public through a revolving series of exhibits, which change four times a year. The collection is housed in a towering antebellum building with the temple front that was built in 1856 as St. James Chapel Methodist Church. The Postal Museum at Meeting and Broad Street, housed in the imposing granite post office building constructed after the Great Earthquake of 1886, is another free museum that tourists usually miss. The building has a grand Victorian era interior and kids and adults alike will enjoy the turn-of-the-century post office still housed inside, with its postal memorabilia and artifacts harkening back to horse-drawn mail delivery days.

Sources:

- Jonathan Poston. Buildings of Charleston. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

- Library of Congress. Historic Photograph Collections.

- Robert Wyeneth. Preservation For a Living City: Historic Charleston Foundation. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2000.

- Stephanie Yuhl. Golden Haze of Memory: The Making of Historic Charleston. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- City of Charleston. Tour Guide Training Manuel.

- https://www.charlestonmuseum.org/support-us/about-the-museum/

- https://www.charlestonsmuseummile.org

- https://schistory.org/museum/

- https://explorecml.org/visit/cml-exhibits/

- https://www.visit-historic-charleston.com/karpeles-manuscript-museum-charleston.html

- http://oldslavemartmuseum.com

- https://www.charleston-sc.gov/160/Old-Slave-Mart-Museum

- https://www.powdermagazine.org

- https://www.edmondstonalston.org