Cannonborough-Elliottborough

By Christina R. Butler/Butler Preservation for Charleston Empire Properties – 8 December 2019

Situated in the heart of the historic district near the Ashley River and bounded by King Street on the east, U.S. Highway 17/Crosstown on the north, president Street on the West, and Bee and Morris Street on the south, sits Cannonborough-Elliottborough, a unique neighborhood comprised of two earlier boroughs that is today brimming with character and a diverse mix of businesses, restaurants, and residences.

In the colonial era, the Neck, of the land north of Calhoun Street, was outside the town limits and was a mix of farms and marshlands. During the Revolution, the American forces dug trenches between what is now Cannon and Morris Streets to defend the back side of the down, which were still mostly undeveloped at that time.

The American defenses shown on the 1781 Investiture Map. Cannonborough-Elliottborough lies between the first and second parallel.

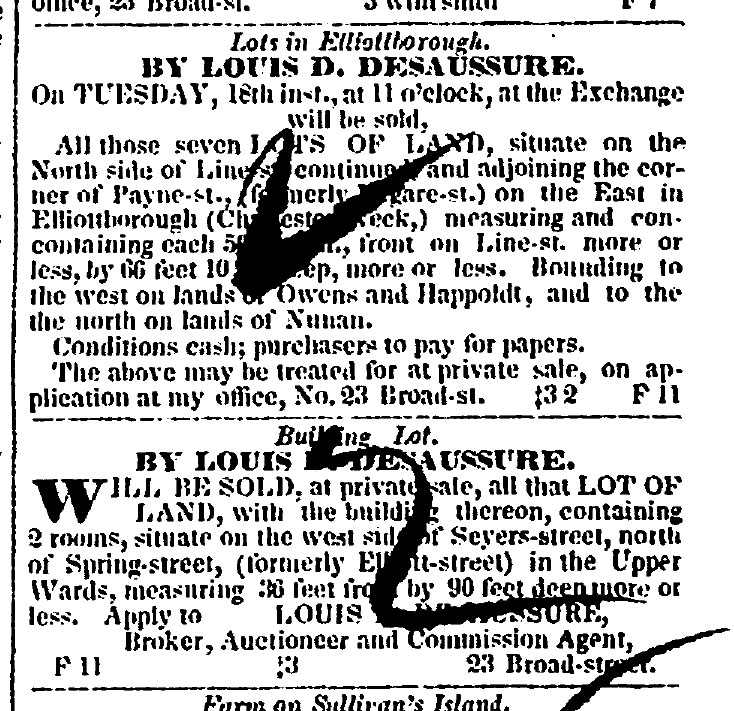

The neighborhoods began in interest after the war, when two enterprising Charlestonians created a pair of new subdivisions. Daniel Cannon, a successful carpenter and lumber mill operator, is the namesake of Cannonborough and Cannon Street. Cannon owned several wind and water powered riverfront mills on the edge of the neighborhood, and his development provided residential lots near the Ashley River. Colonel Barnard Elliott, a planter, military officer, and member of the Provincial Congress, created Elliottborough circa 1785 on lands that passed to him from the original grantee, William Elliott. Spring Street was originally named Elliott Street in the family’s honor. Elliottborough’s original boundaries make up the eastern portion of the neighborhood today, nearer to King Street.

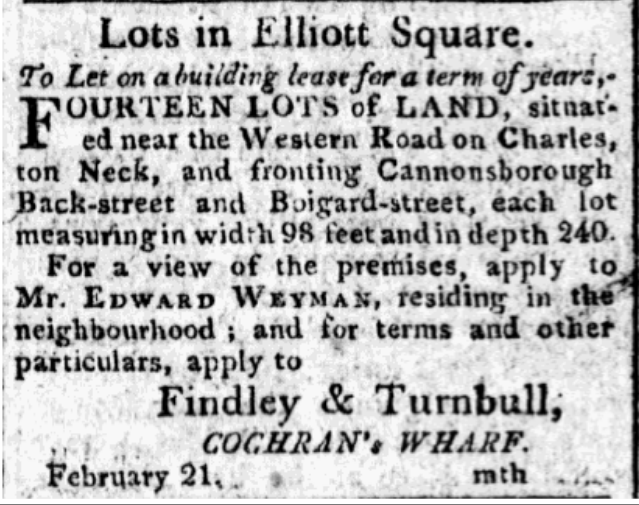

Real estate ads from 1803 and 1851.

During the War of 1812, the neighborhood was fortified once again by the American forces, who constructed a line of earthen fortifications replete with a moat, near present day Line Street (the fortifications are the origin of the street’s name.) In the nineteenth century, the west edge of the neighborhood was bordered by marshes, millponds, wharves, and even a causeway constructed by Charleston Bridge Company. Most of the lowlands were filled gradually for development, and the Ashley River is now several blocks further west than it was originally.

An 1883 map shows the War of 1812 fortifications.

Cannonborough-Elliottborough became a diverse neighborhood with a mixture of industrial businesses, large “urban plantations” with fine gardens, modest farms, and small cottages and tenements. Irish and German immigrants, Jewish residents, free black, enslaved, and native born white artisans called the area home in the nineteenth century.

By the 1840s, residents in Cannonborough were petitioning the city for new streets to better connect their area with denser development in the original town.

1844.

In 1850 the Neck was annexed, making Cannonborough-Elliottborough part of the City of Charleston and causing a building boom of new residences. Several property owners including the Cochrans, McGraths, and Bowens subdivided larger tracts into lots for small houses and trade workshops. During the Civil War, Cannonborough-Elliottborough was outside of Union artillery range and while the lower peninsula was virtually deserted, working and middle class residents continued business as usual on the Neck.

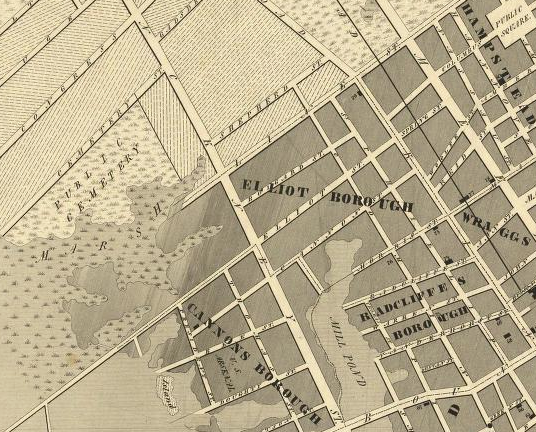

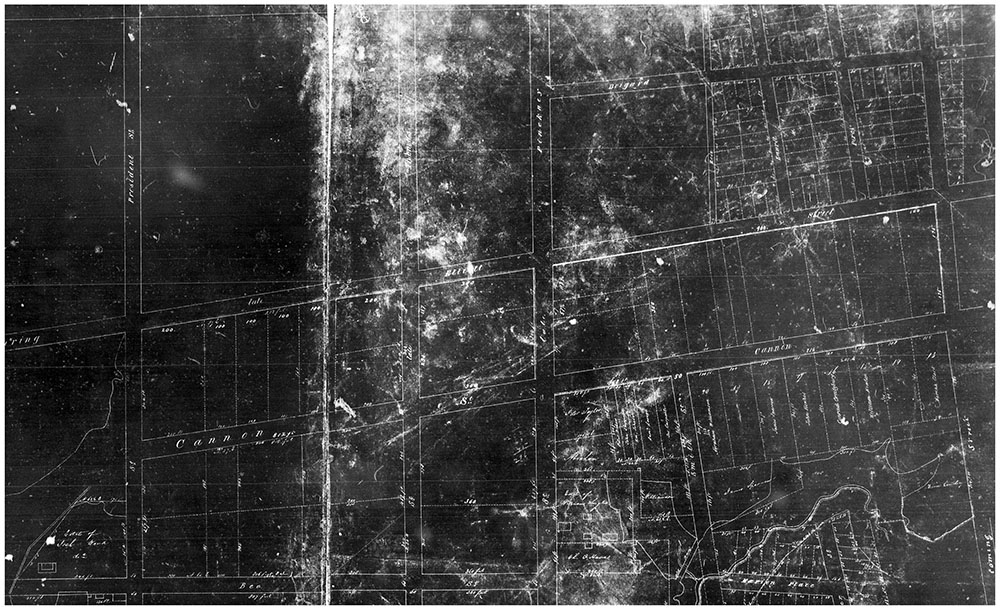

An antebellum subdivision plat, west end of Cannon Street.

A plat showing new building lots on Elliott (Spring), Cannon, and President Streets.

Architecture is as varied as the residents of the neighborhood over time, with a mix of large suburban mansions, two story wooden singles houses, and more modest freedman’s cottages, in an eclectic variety of styles from Greek Revival to vernacular, and even some modern infill, such as the newer townhouses that dot Cannon and St. Philip Streets. There was a second building boom around the turn of the twentieth century, when stately Victorian side hall houses with Queen Anne details were erected along Ashley and Rutledge Avenues (which at that time were on the trolley line.)

Between Coming and St. Philip, the large houses with front yards give way to smaller two story single houses situated right on the sidewalk, most with one story simple piazzas.

There are also several landmark buildings, such as the Karpeles Museum at Spring and Coming Streets, which was constructed in 1856 as a Methodist church, replete with a large portico with Corinthian columns modeled after the Temple of Jupiter in Rome. The cemetery on Coming Street, with its beautiful marble headstones and wrought iron gate, is one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in the country, founded in 1762. There are several neighborhood churches, such as 46 Cannon Street, constructed in 1888 as a mission church, which became Cannon Street Baptist Church in 1893, and was again renamed in 1913 as New Cannon Street Baptist Church and became an African American congregation. By

the 1930s and until the early twenty first century, Spring Street and Cannon Street boasted a thriving black business district, with physicians, lawyers, and various shops to serve the African American community on the upper peninsula.

Like many city centers across the United States, Charleston experienced a population exodus

after World War II as residents moved to new suburbs off of the peninsula. Cannonborough-Elliottoborough received an additional blow when the US Crosstown opened in the 1960s, and leading to the demolition of blocks of houses and severing part of the neighborhood; the modern highway still acts as the neighborhood boundary today. One of the worst casualties of twentieth century change was the Islington Manor, a grand brick and stucco three story house with Federal style piazzas, a hipped slate roof, and large garden. The house was also an important site for Civil Rights history. Dr. Alonzo McClennan purchased it in 1897 and converted it into the Colored Hospital and Training School for Nurses, providing important education opportunities for black residents during the age of segregation. The house was demolished in 1960 as MUSC expanded their campus.

Islington Manor, Historic American Buildings Survey.

By the 1990s, the city began focusing its attention on revitalizing Cannonborough-Elliottborough. They completed a traffic study and converted Spring and Cannon to two way, which has slowed traffic and led to a vibrant commercial corridor. Until recently, Cannonborough-Elliottoborough had a high percentage of vacant properties and dilapidated homes, but in the past ten years, the area has been gentrifying and becoming increasingly popular as it returns to its original integrated composition. Urban planners Robert and Company explained, “while there is not the concentration of grand mansions or historical markers found elsewhere on the peninsula, C-E provides a history of the common citizen, local commerce, and vernacular architecture of Charleston. As it remains today, the community is a place or residence and business for genuine Charlestonians.” Residents in Cannonborough-Elliottborough can enjoy a mix of trendy bars and restaurants and neighborhood corners stores, interspersed with blocks of quiet residential architecture.

If you are considering property in the Cannonborough-Elliotborough area, give one of our agents at Charleston Empire Properties a call of fill out a contact us form. We are very familiar with the Cannonborough-Elliotborough real estate market and keep up to date on all of the area’s and surrounding area’s listings. With our vast experience and expertise, make Charleston Empire Properties your choice in Cannonboroug-Elliotborough relators. We can help you find the property of your dreams!

Sources:

–

City

of Charleston. Spring and Cannon Corridor

Plan. 1998

–

Charleston

County Public Library. Vertical files:

Neighborhoods: Cannonborough-Elliottborough.

–

Charleston News and Courier. Charleston, South Carolina, 1803- present.

(Renamed Charleston Post and Courier in

1996.)

–

Robert

and Company. Cannonborough-Elliottborough

Area Character Appraisal. Charleston: City of Charleston, 2009.

–

Smith,

Henry A.M. “The Baronies of South Carolina”, South Carolina Historical Magazine. Vol. 15, No. 4 (1914), 2-18.

–

McCrady

plat series

–

Christina

Butler. Lowcountry At High Tide. USC

Press, 2020.

–

Nicholas

Butler. “Grasping the Neck.” https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/grasping-neck-origins-charlestons-northern-neighbor