The Lowcountry landscape boasts breathtaking marshes, beaches, and historic communities, but perhaps some of the most hauntingly beautiful and complex sites are South Carolina’s plantations. Several, including Drayton Hall, Middleton, and Magnolia Plantations on the Ashley River, Boone Hall on the Cooper River, McLeod on James Island are open to the public, and each offer a unique and enlightening experience of the state’s rural past.

Charleston’s beautiful architecture and wealth would not have been possible without the supporting plantations and rural landscape of the surrounding Lowcountry, where crops and foodstuffs were grown for South Carolinians, and plantation cash crops like rice, indigo, and cotton were cultivated for distant consumers from New England to the European market. Visitors are often struck by the dichotomy of plantation architecture, with grand houses juxtaposed against the simple homes of the enslaved. Plantation landscapes are beautiful, but they were also places of exploitation and hardship. The plantations featured in this blog all strike a balance between sharing the architectural splendor and romantic planned gardens with sharing the stories and experiences of the enslaved, many of those descendants continued farming on the same land into the twentieth century.

Hundreds of plantations lined the Lowcountry coast, of varying sizes ranging from a few dozen to thousands of acres. Each was unique, but most of the historic landscapes that are open to the public today were the opulent country seats for planters who often owned several plantations. Plantations were self-supporting communities, which typically included a grand residence for the elite property owners, outbuildings including kitchen houses, carriage houses, and stables to support the planters, and ornate manicured gardens for pleasure strolling. Working buildings included larger stables of water buffalo, work horses, and mules; storage barns; curing sheds and mills; blacksmith and carpentry shops; and housing for the slaves who did the work to make the household function and the plantation profitable. Enslaved people cultivated the land, produced and packed crops, worked as maids, butlers, and cooks in the big house, and did various skilled trades.

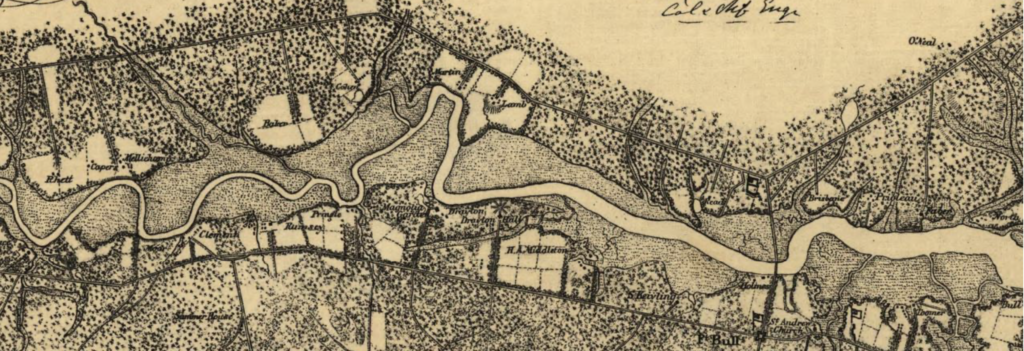

Many Lowcountry plantations were located close to a river for ease of shipping, or near tidal creeks, swamps, and marshes, which could be impounded, and the water controlled for agricultural production. Rice plantations, for example, often had complicated tidal irrigation systems that used the actions of the tidal cycles to flood the fields with fresh water, which required the expertise of farmers who were intimately familiar with the Lowcountry landscape, because any salt entering the fields if the tidal gates were not closed at just the right time could destroy an entire crop.

The architectural style and grandeur of the plantation house varied with the wealth of the owner and what ornamental features were popular when the house was constructed. Some were updated several times and show a story of evolution, though many were destroyed by Union troops or enterprising looters. After the American Civil War, few planters had funds for repairs, much less stylistic upgrades. Many had supported the Confederacy and had to petition to the United States government to become citizens again. Some freed people remained on the plantations where they had been enslaved, now as sharecroppers or paid farmers. Their descendants rented land and houses on part of McLeod Plantation, for example, into the late twentieth century. Other freedmen purchased their own land- often part of former plantations- to start their new lives as farm owners.

On the banks of the Ashley River and just a half hour drive from Charleston are three plantations whose origins date to the early colonial times. They are side by side but over a mile apart from each other, showing the sheer size of the planters’ holdings. Drayton Hall (https://www.draytonhall.org) belonged to the Drayton family until 1974, when descendants sold the house to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and the nationally significant house was opened to the public. Drayton Hall was constructed in the grand Georgian Palladian style (during the reigns of the Kings George, with Renaissance and neoclassical details) around 1742. Drayton Hall has been preserved- while it is not furnished, visitors can see the beautiful architecture elements of up close and unrestored. Drayton has a lovely café and a new state of the art museum, which displays artifacts, furniture, and documents for the plantation’s past, as well as a slave cemetery, and a few outbuildings. Expert guides interpret the house for guests, who can then stroll the grounds along the river.

Middleton Place was established in the 1730s by the Middleton family, who were wealthy planters as well as important politicians (Arthur Middleton was a signatory of the Declaration of Independence). At their peak of wealth, the Middletons owned 20 plantations totaling 50,000 acres, and 800 enslaved people. Middleton Place was the family’s seat and was built to entertain and impress. Visitors in the eighteenth century and today approach via a long oak-lined driveway that leads to a high spot where the now-lost grand house once stood.

The grand house was destroyed in 1865 and family moved into one of the dependency buildings after the Civil War, which is, in itself, a grand building. The highlight of Middleton Place is the breathtaking formal parterre gardens, which date to 1741. They terrace down toward two butterfly lakes, and further to the Ashley River. Middleton Foundation states, “The historic preservation work and interpretation of history at Middleton Place focuses on major contributions of the Middleton family as well as the enslaved Africans and African Americans who lived and worked here. The stories are a microcosm of United States history. From the early Colonial period through the Revolution, the early Republic, the Civil War era and beyond, they made a mark on the land, the colony, state and nation.”

There are beautiful garden rooms and more secluded paths further from the house. Visitors can take a guided house tour, visit a slave dwelling for a self-guided interpreted exhibit titled “beyond the field: slavery at Middleton Place”, can walk the gardens for hours, and visit a gift shop and commercial garden near the parking area (https://www.middletonplace.org). A large stable yard features heritage breeds like water buffalo, horses, geese, and sheep, and historic interpreters demonstrate traditional trades like basket weaving and blacksmithing. Middleton has a phenomenal restaurant, and hosts book talks and lectures in their pavilion building, as well as weddings and other events. Stay next door at Middleton Inn and book a trail ride and see part of Middleton’s grounds on horseback for the ultimate Lowcountry getaway.

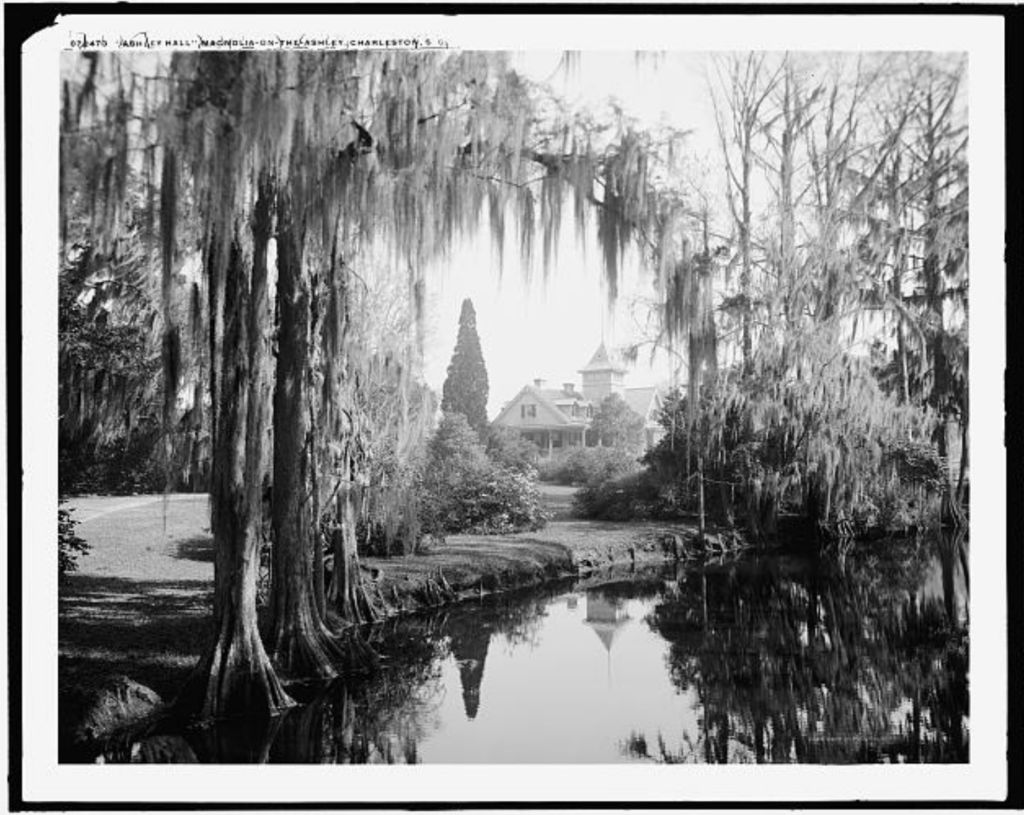

Magnolia Plantations and Gardens was also created by the Drayton family in 1679. The current residence was mostly rebuilt after the Civil War and has a unique Victorian aesthetic. Magnolia has beautiful garden trails lined with colorful azaleas, camelias, and cypress swamps. The gardens were begun in the height of the romantic era in the 1840s by Rev. John Grimke Drayton. Magnolia has been open to the public since the 1870s, which allowed the family to generate the income needed to maintain the plantation and avoid selling acreage.

Descendants of the enslaved lived on the plantation’s “slave street” into the twentieth century. Magnolia has 66 acres of gardens, 6 miles of walking trails, the big house (for an extra fee), a snack shop and a Wildlife Center with rescued lowcountry animals and a swamp boardwalk. https://www.magnoliaplantation.com/plan-your-visit All tickets included admission to the poignant “From Slavery to Freedom” tour that takes guests into the slave cabins. If you’re lucky, you might have the chance to hear the tour from historian Joe McGill, founder of the Slave Dwelling Project (https://slavedwellingproject.org).

Boone Hall Plantation in Mount Pleasant, located in the midst of what was once the agricultural Christ Church Parish (https://www.boonehallplantation.com), was founded in 1681 by Major John Boone on the Wampacheone Creek. It is one of the oldest plantations in the United States that is still in operation. The Horlbeck family owned Boone Hall in the antebellum era and manufactured bricks at the site using the rich local clay; the Horlbeck brothers also had a contracting company that specialized in brick masonry in Charleston, cornering the market with the material and the craft. They owned dozens of enslaved master brick layers. Boone Hall also boasts an important series of brick slave cabins; this is rare, as slave dwellings were usually simple wood frame buildings.

The Stone family bought the Boone Hall in 1935 and erected the current grand Colonial Revival plantation house, which is furnished with antiques and is part of the tour. The site today cultivates heirloom crops and hosts festivals and a fall pumpkin patch. Boone has a large pavilion and is a popular wedding venue. It’s is also a great family visit, as the grounds have a butterfly pavilion, horses and farm animals, an optional farm tractor ride.

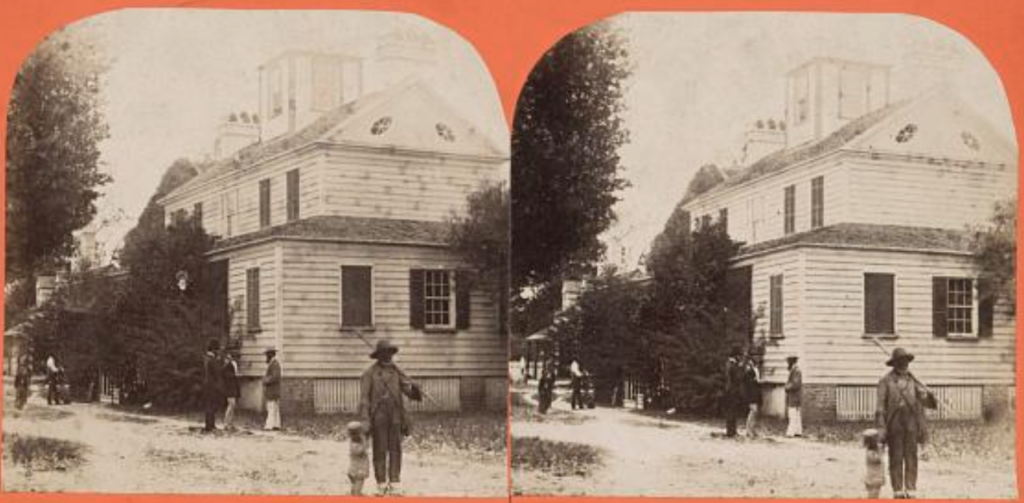

McLeod Plantation lies off busy Folly Road on James Island just ten minutes from Charleston, and it offers a reminder of how much more rural the Lowcountry was until recent decades. McLeod (https://www.ccprc.com/1447/McLeod-Plantation-Historic-Site) is owned by Charleston County Parks, which took a bold move in purchasing the plantation, restoring it, and opening it for tours that focused on the slave experience rather than the grand house and opulent lifestyle of the McLeod family.

The big house is a timber framed building with wood siding and simple massing, but with a grand colonnaded portico overlooking the property. Guests can walk through the house self-guided, and visit the gift shop and museum in the ticket office on the way in. McLeod is unique because a series of slave cabins, a dairy that predates the current house, and a cabin converted into a praise house all survive, where today skilled guides explain the life of the enslaved, and their descendants who remained at McLeod. The parks department explains that, “established in 1851, McLeod Plantation has borne witness to some of the most significant periods of our nation’s history. Today McLeod Plantation Historic Site is an important 37-acre Gullah/Geechee heritage site that has been carefully preserved in recognition of its cultural and historical significance. The grounds include a riverside outdoor pavilion, a sweeping oak allée, and the McLeod Oak, which is thought to be more than 600 years old. It is a place like no other, not frozen in time but vibrant, dynamic, and constantly evolving, where the winds of change whisper through the oak trees and voices from the past speak to all who pause to listen. McLeod Plantation was built on the riches of sea island cotton – and on the backs of enslaved people whose work and culture are embedded in the Lowcountry’s very foundation. It is a living tribute to the men and women and their descendants that persevered in their efforts to achieve freedom, equality, and justice.” A fitting tribute to the complex past from which the Lowcountry’s evocative plantation landscape evolved.

Sources:

- Library of Congress historic photographs

- William and Agnes Baldwin. Plantations of the Lowcounty: South Carolina 1697-1987. Legacy Publishing, 1987.

- Stoney, Samuel G. Plantations of the Carolina Low Country. Columbia: Carolina Art Association, 1938.

- A.M. Smith. Historical Writings of Ham Smith. Columbia: Reprint Company, 1985.

- Magnolia Plantation National Register nomination form

- McLeod Plantation National Register nomination form

- https://www.middletonplace.org

- https://www.draytonhall.org

- https://www.magnoliaplantation.com

- https://slavedwellingproject.org

- https://www.ccprc.com/1447/McLeod-Plantation-Historic-Site

- https://www.boonehallplantation.com