Charleston’s best-known and most loved parks, which dot the southern and southeastern end of the city, each have a unique historical background but share one thing in common: all were reclaimed from the Cooper and Ashley rivers as the city expanded and grew over time. Best water parks in Charleston SC–The High Battery, Murray Boulevard/Low Battery, White Point Garden, Hazel Parker Playground, and even the most recent greenspace, Waterfront Park–all began as either fortified landscapes or wharves bustling with maritime activity. Today they are some of the most photographed places in Charleston, and it is easy to see why after spending an afternoon relaxing at any of these breezy city parks boasting spectacular Charleston waterfront park views.

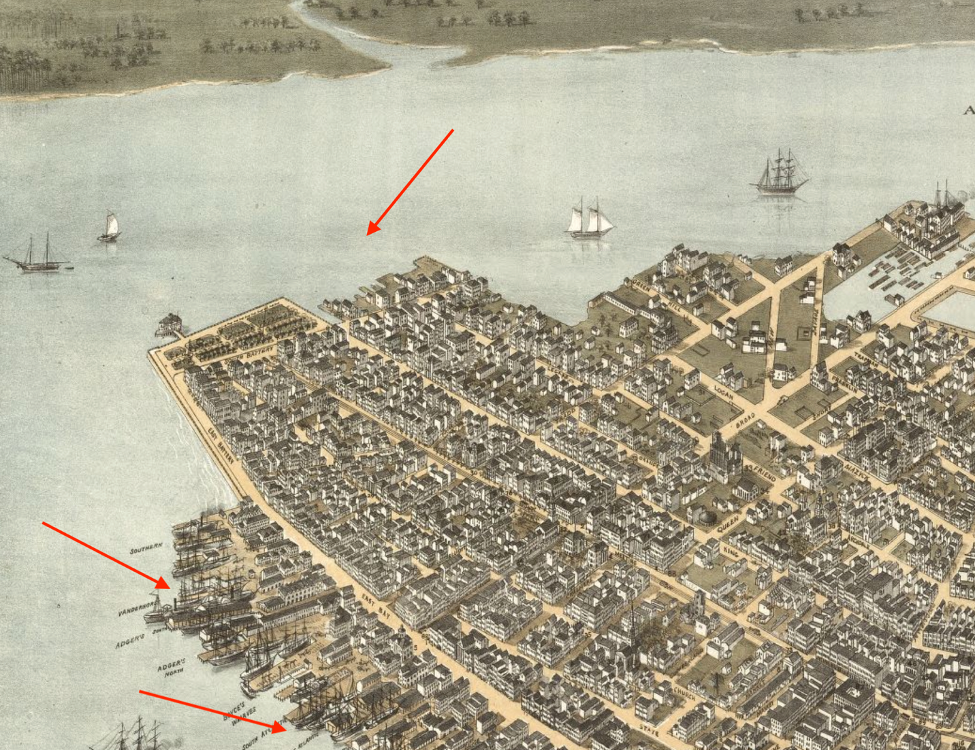

Working in chronological order, we’ll begin with East Battery, also called the High Battery (and erroneously called Battery Park by northerners familiar with a similar park in New York.) East Battery was undeveloped beach and marshes in the colonial era, and it wasn’t until Charlestonians began filling and altering the landscape that the row of famous antebellum houses on view from the Battery promenade became possible. The Battery’s name hints at its earlier life as a militarized landscape, and like Charleston waterfront park named White Point Garden to the south, there were gun emplacements and other fortifications dominating the high ground and protecting the town and Charleston harbor in the eighteenth century. The city began the extension of East Bay Street to be one of the best water parks in Charleston SC (which was then renamed East Battery) in 1788, but early attempts to reclaim with earth and wood proved no match for storm surges and erosion.

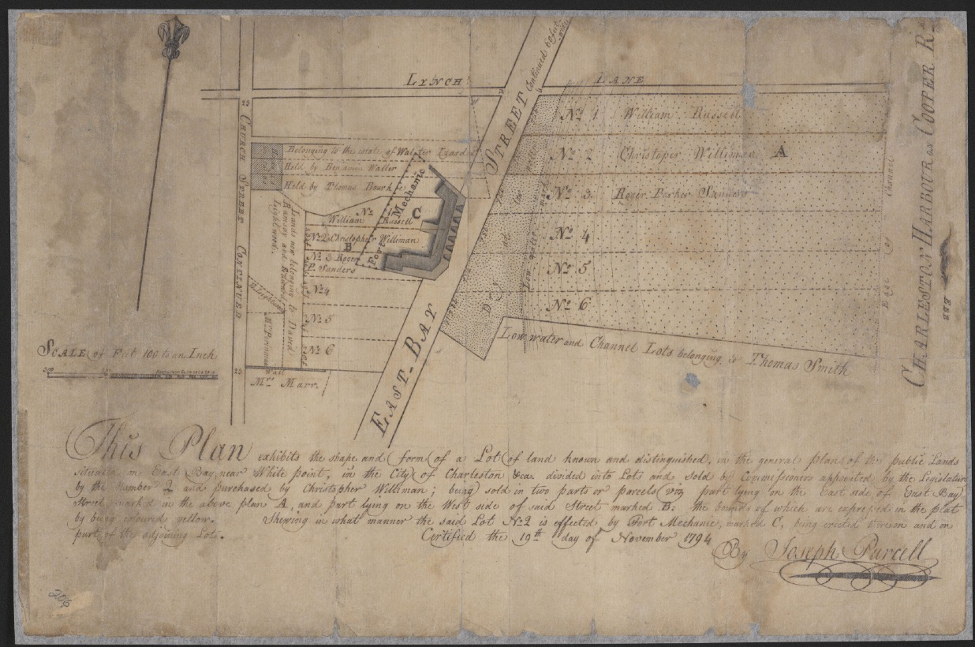

There was a floodgate, pond, and creek where today’s Water Street lies as late as the 1810s. During the War of 1812, as the battery seawall was under construction, an earlier Charleston waterfront park site called Fort Mechanic was reactivated, but by 1818, the seawall was complete, and the promenade was opened to pedestrians and East Battery Drive opened to carriages. The wall was repaired, and the blue flagstones still present today were installed following a hurricane in 1854. A few years later, Charlestonians watched the first shots of the American Civil War at Fort Sumter from the grand mansions along the Battery, and the area was turned into a fortified landscape once more. After the end of that conflict, the area reverted back to a quiet residential neighborhood and repairs were made to erase the damage of war. Aside from a few landscape changes, the Battery has remained the same since.

McCrady plat 206, showing Fort Mechanic and the early phases of East Bay Street continued”, in 1794.

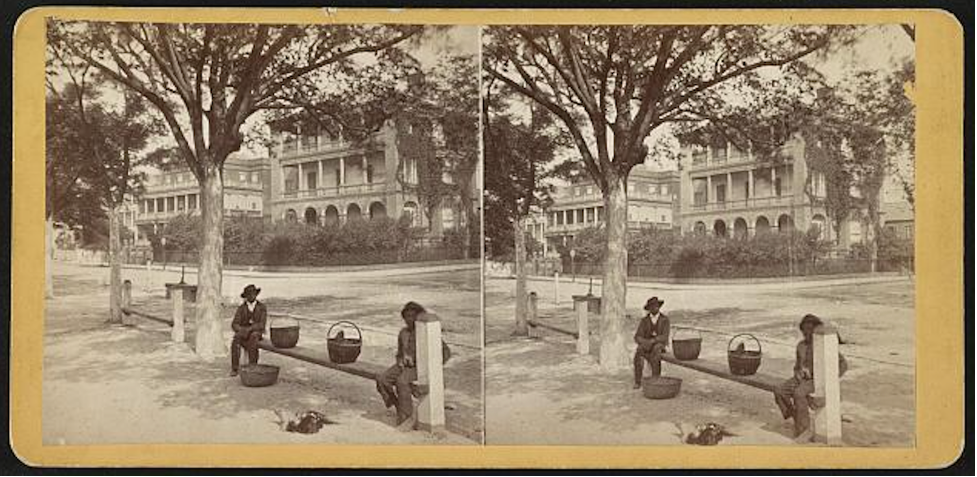

Continuing on East Battery and turning right onto South Battery, the roads give way to White Point Garden, a beautiful four-acre oak-lined Charleston waterfront park with a view of the Charleston Harbor and benches for people-watching and lawns for picnics. White Point is a historic place name used by the Native Americans and early Charlestonians because the area was a bright white beach of sun-bleached oyster shells at low tide and was one of the best water parks in Charleston SC at that time. Like the Battery, White Point’s highlands were fortified in the colonial era, and residents began to build waterfront houses on the original river edge. In the 1830s, the Charleston waterfront park city transformed the area to create the antebellum park that we still enjoy today by creating a new sea wall and filling the lowlands in between. The city closed Fort Street, straightened and reopened part of it as South Battery Street, filled the area with ship ballast and Bermuda stone rubble, and installed horse ties and watering troughs for the carriage horses whose owners drove in the area for recreation.

Mayor Robert Hayne envisioned building a “promenade similar to the Battery in New York,” and there was even a floating bathing house next to the Charleston waterfront park in the river. The park was expanded west to King Street in the 1850s to include additional shell paved walkways for strolling. White Point Garden is lined with monuments to the city’s military heroes, including “Defenders of Fort Moultrie” commemorating the American Revolution, and the more controversial “Confederate Defenders” at the harbor fronting corner of the park. The most ominous is a simple headstone-shaped marker along South Battery that marks the approximate location where famous pirate Stede Bonnet and his crew were hanged for terrorizing English shipping, and where their bodies were buried at the water’s edge. Historic cannons placed along the periphery remind visitors of the Charleston waterfront park’s heritage as a fortified landscape. At the center is a cast iron Victorian bandstand, constructed in 1906 and donated to the city by Martha Williams Carrington in honor of her father; her house overlooked White Point Garden and Mr. Williams lived just a few houses away. It is one of the best water parks in Charleston SC and a favorite wedding location today.

Moving westward from White Point is Murray Boulevard or the Low Battery, which was part of a forty-seven-acre city land reclamation project completed in two phases (1909-1911, 1917-1919) to create dozens of waterfront residential building lots and a long scenic drive and promenade along the Ashley River. Christina Butler notes, “The timing [of the project] couldn’t have been worse because World War One led to material rationing and labor shortages throughout the state, but after almost a decade, the Charleston waterfront park project was complete, linking the White Point Garden area with the earlier reclamations near Colonial Lake on the west side of the peninsula.” All told, the project required 667,000 cubic yards of dredge spoil to fill and create this new section of the city. The Boulevard was named for Andrew Murray, born of humble origins to Scottish parents in 1844. He rose from a laborer at Bennett Rice Mills to a partner in the firm, and was a long time benefactor to the city of Charleston, funding various Charleston waterfront park and paving projects out of his own pocket.

The Low Battery is about to undergo a transformation to be one of the best water parks in Charleston SC as the City of Charleston prepares to rebuild and raise it to better withstand storm surges. The palmetto lined berm between the boulevard auto lanes will remain, but it will be enhanced and dotted with “parklets” featuring seating areas, fishing platforms, and ornamental plantings, making the area even more beautiful than it is today.

If one continues back east and north from the Boulevard and Battery, the reclaimed land gives way to East Bay Street, marking the original high ground of the early Charleston waterfront park city. Across from the famous Rainbow Row lies a hidden gem, Hazel Parker Playground. The entire site lies atop former wharves and docks that were filled slowly over time as the shipping platforms were extended further into the river to accommodate larger modern ships. All trace of industry and maritime activity is gone today (the last commercial wharves in the area ceased operation after World War Two), except for the private and exclusive Carolina Yacht Club next door. The land, formerly owned by the Port Utilities Commission, was developed as a Charleston waterfront park in 1933 as a New Deal project, and then leased to the Navy during WWII.

This park has spacious jungle gyms and playground facilities, a recreational building with restrooms, water fountains, and classrooms for exercise courses and craft activities, as well as tree lined tennis courts and a popular dog park making it one of the best water parks in Charleston SC. The park is renamed for Hazel Parker in 1977, who was a longtime supervisor at the playground from 1942 onward.

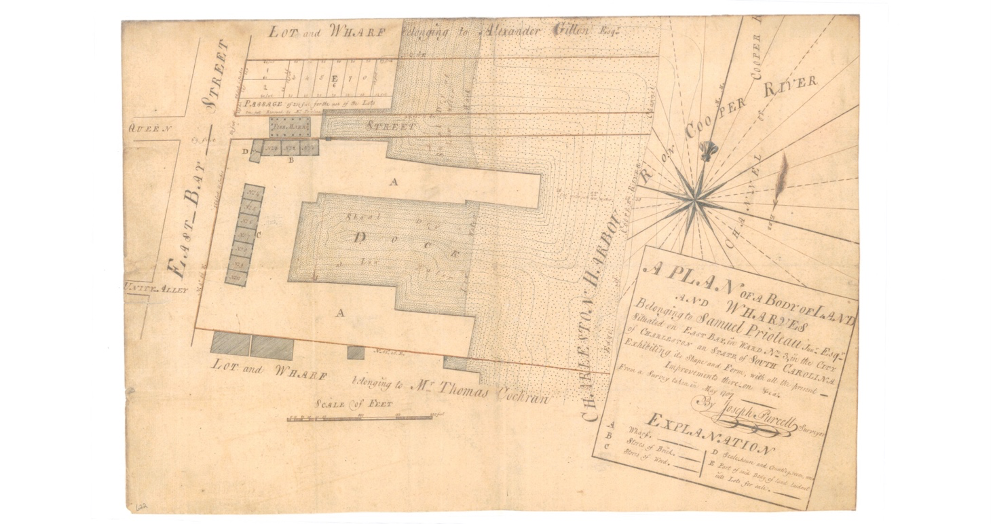

The most recent Charleston waterfront park addition, located several blocks to the north along East Bay Street, is Waterfront Park. This expansive park at the east end of Queen Street was once a vast marshy mud flat next to a large wharf owned by the Prioleau family and with an adjacent city-owned market area.

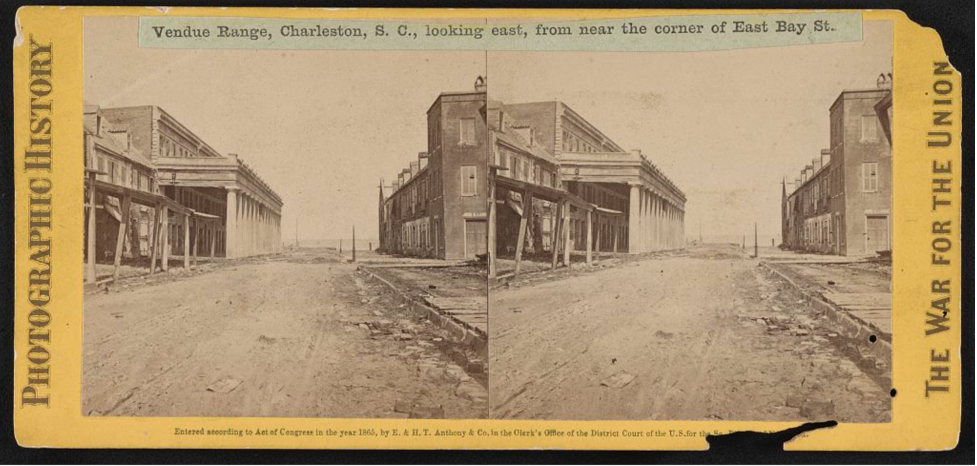

Around 1808, the Prioleaus gave their land to the city, which removed the old market and filled the lowlands. Historian Nic Butler notes that, “along the north and south sides of this short, un-named street arose “ranges” of new commercial buildings. These Charleston waterfront parks, wharf-side buildings weren’t designed for retail sales, however, but rather for vendue sales,” and the area became known as Vendue Range. Like the parks to the south, it became a gun battery during the American Civil War and then reverted back to a maritime streetscape where large ships were packed with southern cotton for export.

By the mid twentieth century, the former vendue area was unceremoniously used for parking, until the late 1970s when the city hatched a plan to redevelop and beautify this waterfront area. After Hurricane Hugo in 1989, the Waterfront Park was opened in May of 1990 by Mayor Joe Riley. Today it is one of the best water parks in Charleston SC and is best known for some of the best sunset and sunrise views in the city from park bench swings on the boardwalk leading to the Cooper River, and to its iconic pineapple fountain and jet fountain that double as water parks.

Discover the charm of Charleston’s waterfront parks with Charleston Empire Properties! Find your ideal home near picturesque parks, just steps from beautiful green spaces, and enjoy coastal living at its finest. Dive into our property listings for Charleston SC homes for sale now and contact our expert realtors today to make your dream home a reality!

Sources:

- Nicholas Butler. “Vendue Range: A Brief History.” June 2107. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/vendue-range-brief-history

- McCrady plat collection, Charleston County Deeds Office

- Library of Congress maps and photographs collections

- Christina Butler. Lowcountry At High Tide: Flooding, Reclamation, and Drainage in Charleston, South Carolina. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2020.

- Christina Butler. “Brinks and Boundaries.” Kiawah Legends. https://www.kiawahisland.com/featured/brinks-and-boundaries/

- “East Bay Park”, Charleston News & Courier. Nov 6, 1933. p. 8

- City of Charleston Yearbook, 1909, 1911, 1919, 1933.

- Charleston Parks Conservancy. “White Point Garden.” https://www.charlestonparksconservancy.org/park/white-point-garden

- City of Charleston. “Low Battery Seawall Repair.” https://www.charleston-sc.gov/1193/Low-Battery-Seawall-Repair

- John R. Young. A Walk in the Parks: the definitive guide to monuments in Charleston’s downtown parks. Charleston: Evening Post Books, 2008.

- Robert Whitelaw. Charleston: Come Hell or High Water. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2002.