The west side of Charleston along the Ashley River has grown with the city’s population as Charlestonians reclaimed land to create new residential boroughs. Alongside the new land, Westside Charleston Parks and recreational spaces cropped up in the twentieth century. Some of these gems are well kept local secrets, while others like Joe Riley Ballpark and Hagood Memorial Stadium attract sport fans from across the state.

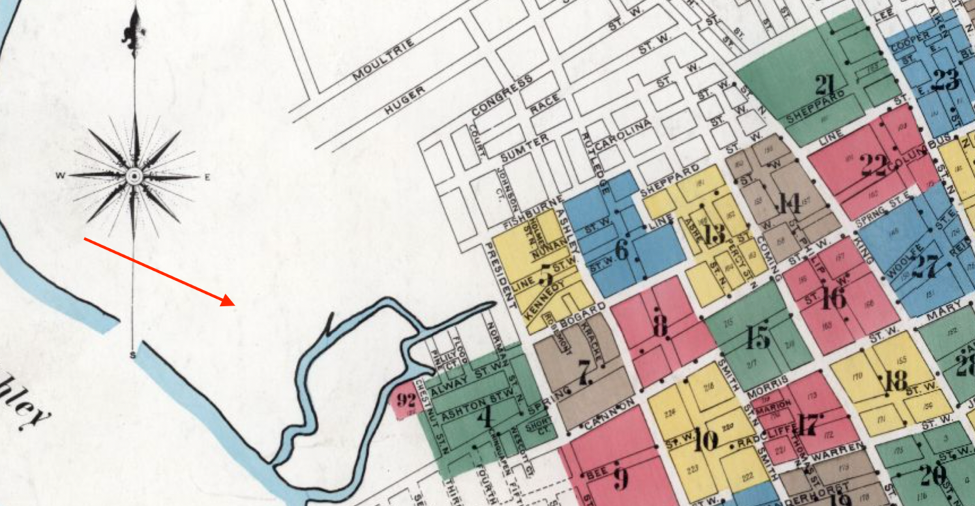

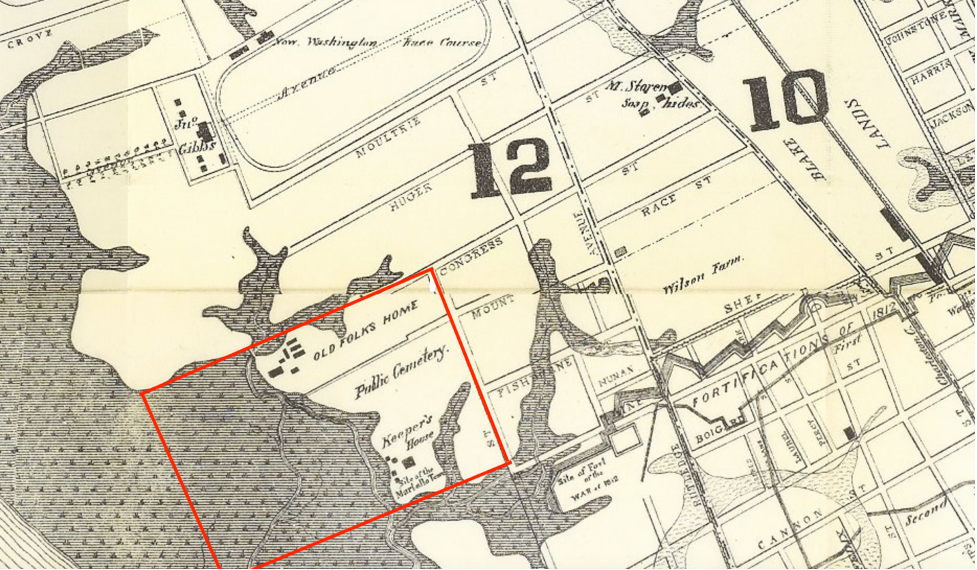

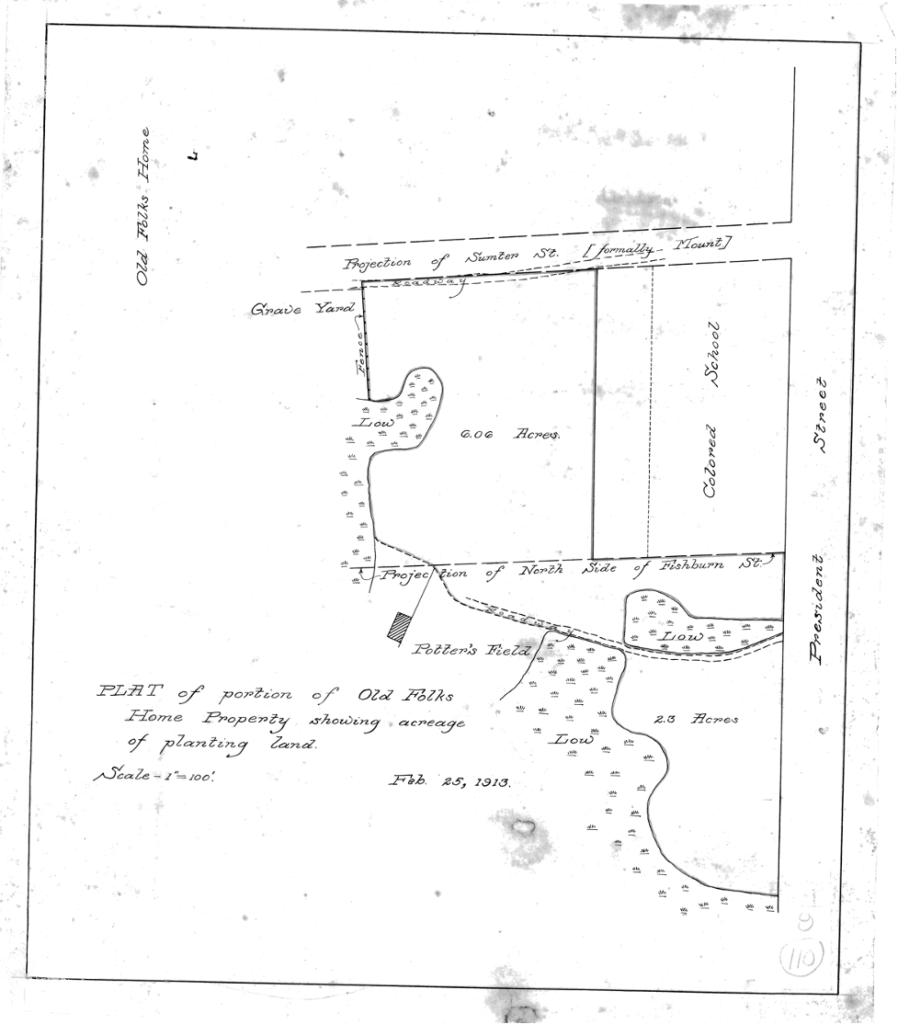

Harmon Field is bounded by Fishburne, Hagood, President, and Line Streets and was once a marsh-fronting tract of land on the outskirts of town, which was part of Pick Pocket plantation in the eighteenth century. Harmon Field is located on a pauper’s graveyard or public cemetery, as well as the site of a Martello tower (a tall brick gun emplacement) and earthwork fortifications constructed near Line Street during the War of 1812. The sports field was created in 1927 with funding from the Harmon Foundation, and it was a segregated park for black Charlestonians in the Jim Crow era. The “Greenbook of South Carolina notes that, “it was for African Americans only until 1964. In 1953, the Cannon St. YMCA established the first black Little League in SC, it played games here. The YMCA entered a team in the state Little League tournament, 1955. White teams boycotted rather than integrate, the Cannon St. All-Stars became state champions by forfeit. The team was invited to the Little League World Series, but not allowed to compete. The state marker is on the President St. side.”

Today, the 13-acre park includes fields for soccer, football, basketball, and baseball, a playground, the Arthur W. Christopher community center, and Herbert Hasell pool, which was recently renovated with a new sunscreen area. The pool was built in 1933 as a segregated facility, and was later named in honor of Hasell, the first black Charlestonian killed in action during World War Two.

Across from Harmon Field on Fishburne Street is Hagood Stadium. Like Harmon Field, the stadium lands were once part of a city-owned lowland that included the “Old Folks Home”, or Ashley River Asylum, which was for destitute elderly African American residents.

The historic Hagood football field that was created in a collaboration between the City of Charleston, which provided the marshlands where the stadium would be built, and the Citadel military college, whose Bulldogs have been playing a the Hagood since it opened in 1927. It has since been expanded to a larger seating capacity and with more nearby parking.

Moving west toward Lockwood Boulevard, baseball and music enthusiasts find Stoney Field and Joseph P. Riley Jr. Park. Stoney Field, which was built in the 1960s atop a filled-in marsh, is the home base for the Burke Bulldogs, the highly competitive football team of the historically black Burke High School next door.

Riley Park officially opened in 1997 and is named for Charleston’s longest serving mayor, who was in office from 1975 until 2016. “The Joe” is home to the Charleston Riverdogs baseball team, which is co-owned by Bill Murray, who is often spotted in full support at the games. The Citadel and College of Charleston’s ball teams also play at the stadium, which explains the “Bulldog clubhouse” with its memorial plaque for Chalmers “Chal” Port, the coach who brought the Bulldogs’ dreams of winning the College World Series to fruition in 1990. The Joe also hosts music concerts and events, including performances by Charlestonian Darius Rucker.

Brittlebank Park lies at the end of Fishburne Street alongside the Ashley River. The neighboring stretch of Lockwood Boulevard was created in the early 1970s, and the surrounding area filled to create future the future park and the Charleston Police Department headquarters across the street.

Christina Butler notes that, “Julius Brittlebank left a portion of his estate to the city in 1967, and the City Council passed a resolution to create a city park with the funds, named in his honor. The twelve-acre park, located north of Spring Street, was begun in 1969 and required fifty-five thousand cubic yards of trash and earth fill, provided by Truluck Construction. The first phase included fill, grading, and planting trees at a total cost of $200,000. The second and third phases involved additional landscaping and construction of recreational facilities and tables. The city matched the Brittlebank family’s donation.” Older locals remember the “city dump” on the river’s edge, where sanitary fill (city refuse picked clean of organic debris) was deposited in layers and then capped in pluff mud to build the park. Today the park has a lush lawn and riverfront paths and is the stage for various city hosted sports events and small festivals. There are boat racks, a playground, waterfront walks, and a large fishing pier with a pavilion overlooking the Ashley River bridges.

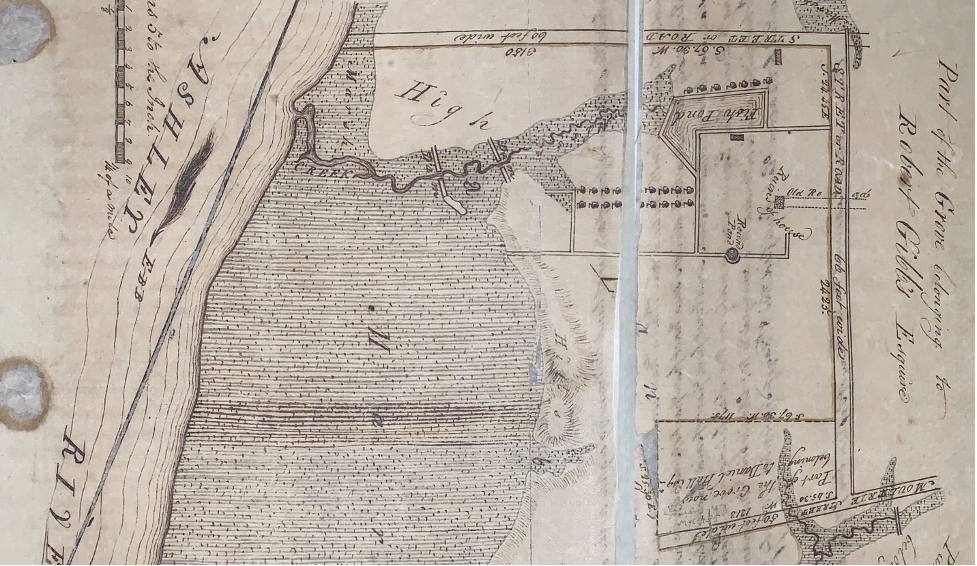

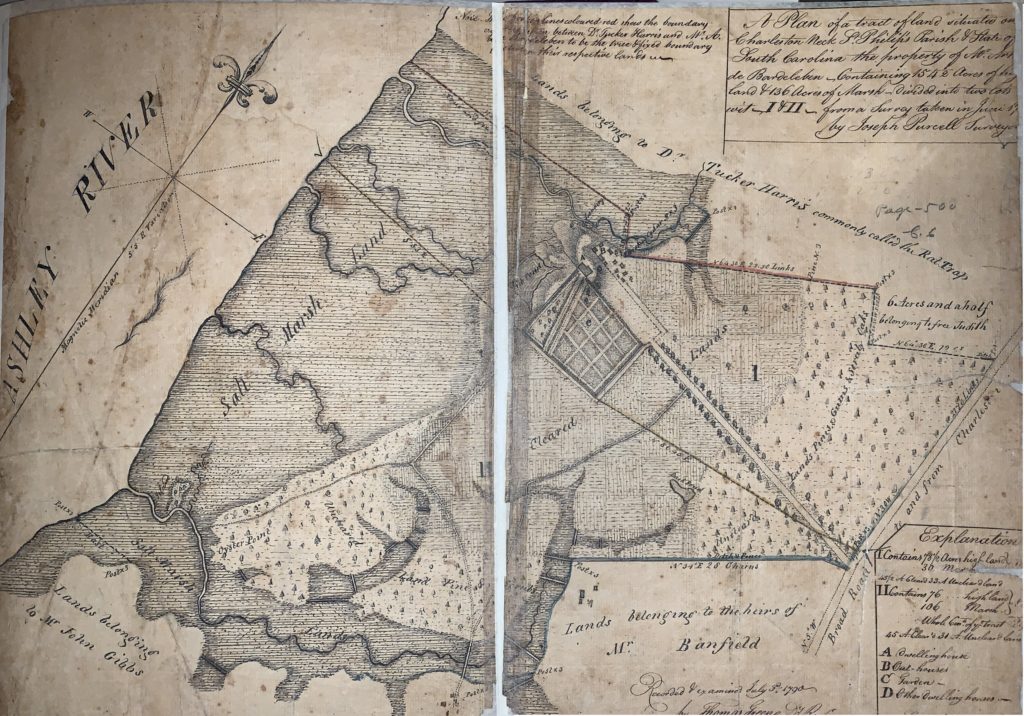

Further north, Lowndes Grove is a historic plantation situated near the river near the foot of aptly named Grove Street. While not a park in the traditional sense, this beautiful estate is popular for weddings and available for rent for the perfect Lowcountry event. John Gibbes created the Grove in the late colonial era, replete with a manor house and formal gardens. The house was destroyed during the American Revolution and replaced with the current house, with its high raised basement, circa 1786.

The Lowndes family purchased it and renovated the house to include a wide colonnaded front porch around 1830, and it later passed to Frederick Wagener, for whom adjacent Wagener Terrace neighborhood is named. The house is listed on the National Register and is currently managed by Patrick Properties.

Longborough Park is the newest Westside Charleston Park, and after a legal dispute between residents and the developer and the city of Charleston, was recently solidified as a public park. It is located near the end of Mary Ellen Drive on the edge of the neotraditional Longborough, a recently constructed planned urban development. The park and surrounding neighborhood were once part of Sans Souci plantation.

It is one of the best views of the marshes that early residents would have found lining both sides of the peninsula before the city developed, and it consists of sand trails through the low tree, to a small fishing pier with benches along the Ashley River’s salt marshes.

Sources:

- McCrady plat collection. South Carolina State Archives.

- Charleston County Register of Deeds plat collections

- Smith, Henry A.M. “Charleston and Charleston Neck”, South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol. 19, No. 1 (January 1918), 3-76.

- Christina Butler. Lowcountry at High Tide: Flooding, Land Reclamation, and Drainage in Charleston, South Carolina. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2020.

- “Greenbook of South Carolina.” https://greenbookofsc.com/locations/harmon-field-cannon-street-all-stars/

- City of Charleston. “Harmon Field.” https://www.charleston-sc.gov/Facilities/Facility/Details/78

- “ Historical Map of Charleston, 1670-1883.” City of Charleston Yearbook,

- National Register. “Lowndes Grove.”

- Post and Courier. https://www.postandcourier.com/news/charlestons-longborough-park-battle-over-docks-nearing-a-close-13-years-after-it-started/article_bde48b9c-65d0-11e9-a9e6-3b368ba530bc.html

- Bill Burr. “Pauper’s Field”: digging deeper into history of bones unearthed in Charleston.” https://abcnews4.com/news/local/paupers-field-digging-deeper-into-history-of-bones-unearthed-in-charleston March 2017.

- Paul Bowers. “Burke’s football stadium sinking into the Ashley River.” Post and Courier, 14 September 2020.

- “Harmon Field.” Post and Courier, 23 December 1928.