Mazyck-Wraggborough: Charleston’s Garden District Neighborhood

By Christina R. Butler/Butler Preservation for

Charleston Empire Properties – 25 April 2020

Like many of Charleston’s historic neighborhoods, Mazyck-Wraggborough started as rural pasture land before being subdivided as two distinct neighborhoods baring their creator’s names. Mazyck-Wraggborough is filled with beautiful Greek Revival and folk Victorian residences, owing to a flurry of antebellum development and another building boom in the late nineteenth century. Bounded by Calhoun Street to the south, Mary Street to the north, Meeting Street on the west, and Cooper River on the east, the neighborhood today boasts four parks for residents and is known for its quiet ambience- it is even called the Garden District of Charleston by some. With several museums and blocks of slate lined sidewalks, it is truly a history lover’s dream neighborhood.

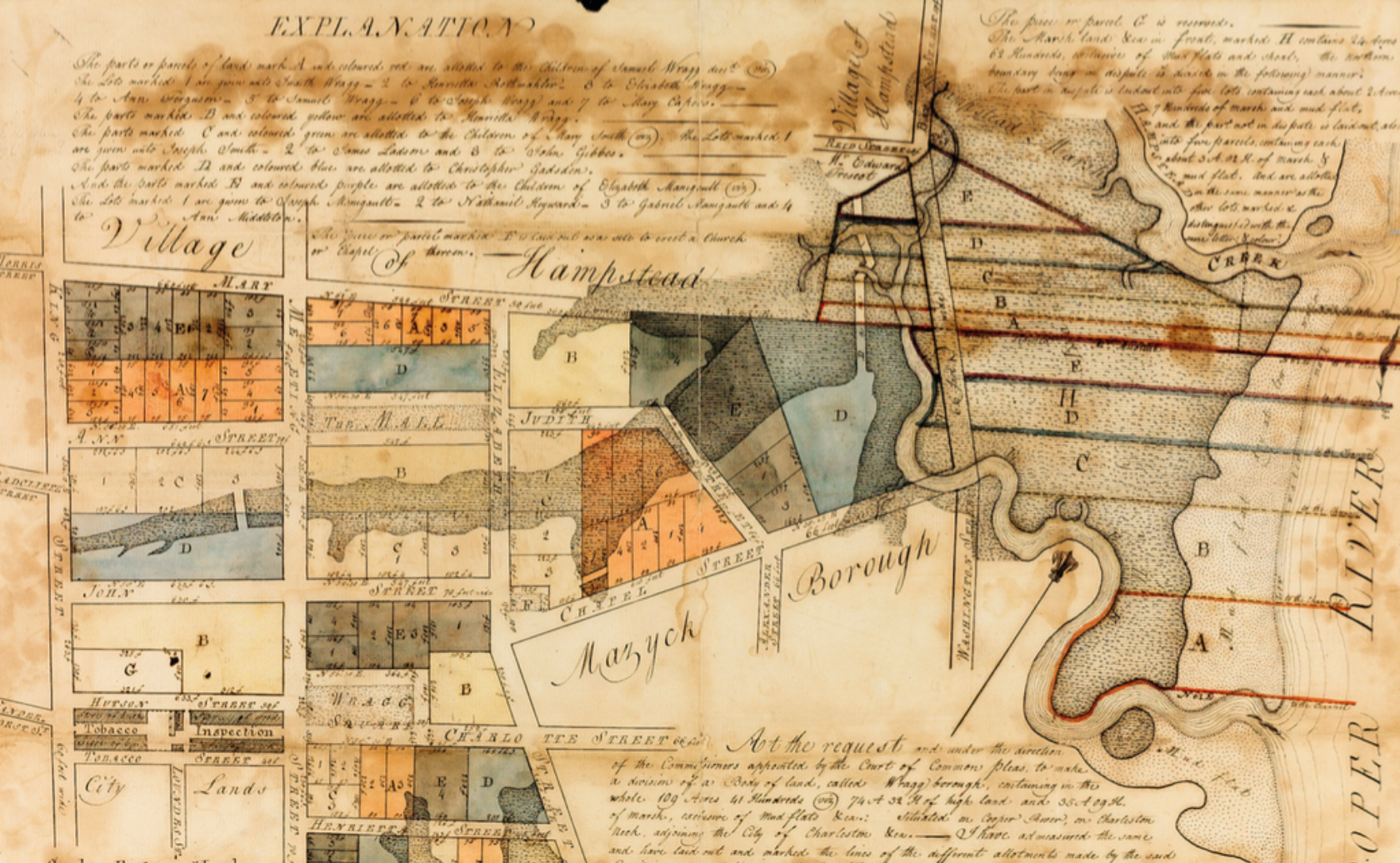

The land that became Mazyck-Wraggborough was out of town in the colonial era, with only a few farm houses and pastures dotting the marshy landscape. Joseph Wragg had extensive property on the Charleston Neck, and in 1758 left 79 acres to his eldest son, John Wragg. After his death, John Wragg’s heirs created his namesake borough in 1796, with streets named for family members: John, Ann, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Henrietta, Judith, and Mary.

The original subdivision plat of Wraggborough, by Joseph Purcell, 1796. South Carolina Department of Archives and History.

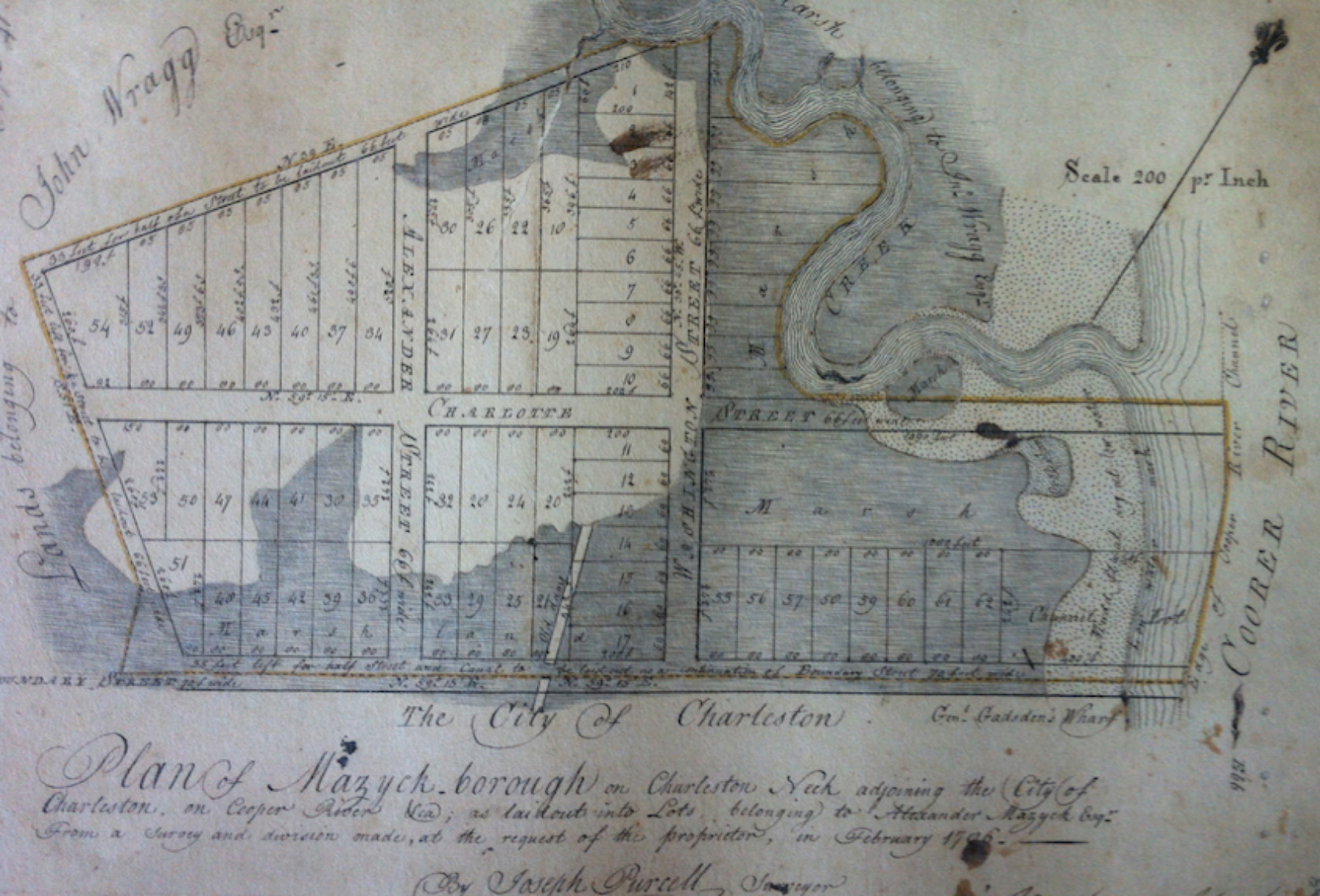

Alexander Mazyck had already laid out his eponymous borough in 1786, bounded by Calhoun (Boundary) and Alexander Street. His pasture was the site of the famous Liberty Tree, where Christopher Gadsden held meetings to advocate for American independence in 1766.

Plan of Mazyckborough on Charleston Neck, by Purcell, 1786. Charleston Register of Deeds.

As suburban neighborhoods outside of city limits, Mazyck-Wraggborough boasted large lots and attracted elite property owners who built beautiful suburban villas with large yards surrounded by wrought iron fences, like the 1832 Elias Vanderhorst house and the 1809 Dr. Anthony Toomer house on Chapel Street (currently on the market).

Dr. Anthony Toomer House, circa 1809.

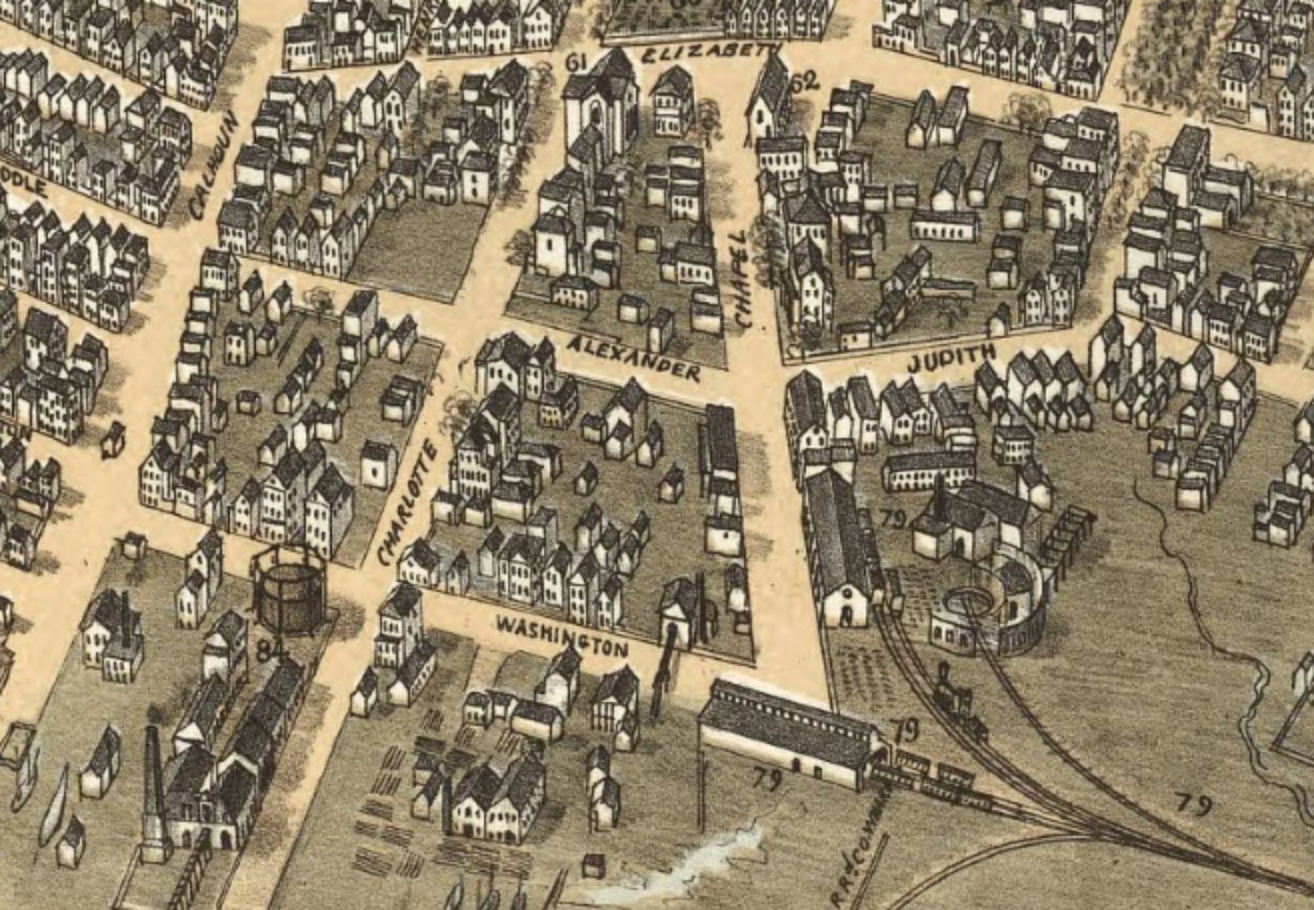

Creeks and marshes stemmed inland from the Cooper River, which residents filled over time to develop the two neighborhoods. Mazyckborough, nearer to the river, had several industrial enterprises along its eastern edge near the Cooper River. Part of the neighborhood is still owned by South Carolina Electric and Gas (a small brick gas house built in 1855 is a visual reminder of earlier industry in the neighborhood) and by the State Ports Authority. Another example is the cirica 1866 Northeastern Railway Depot building with its arched brick windows and latticework gable ends, which is now the popular East Bay Beirgarten.

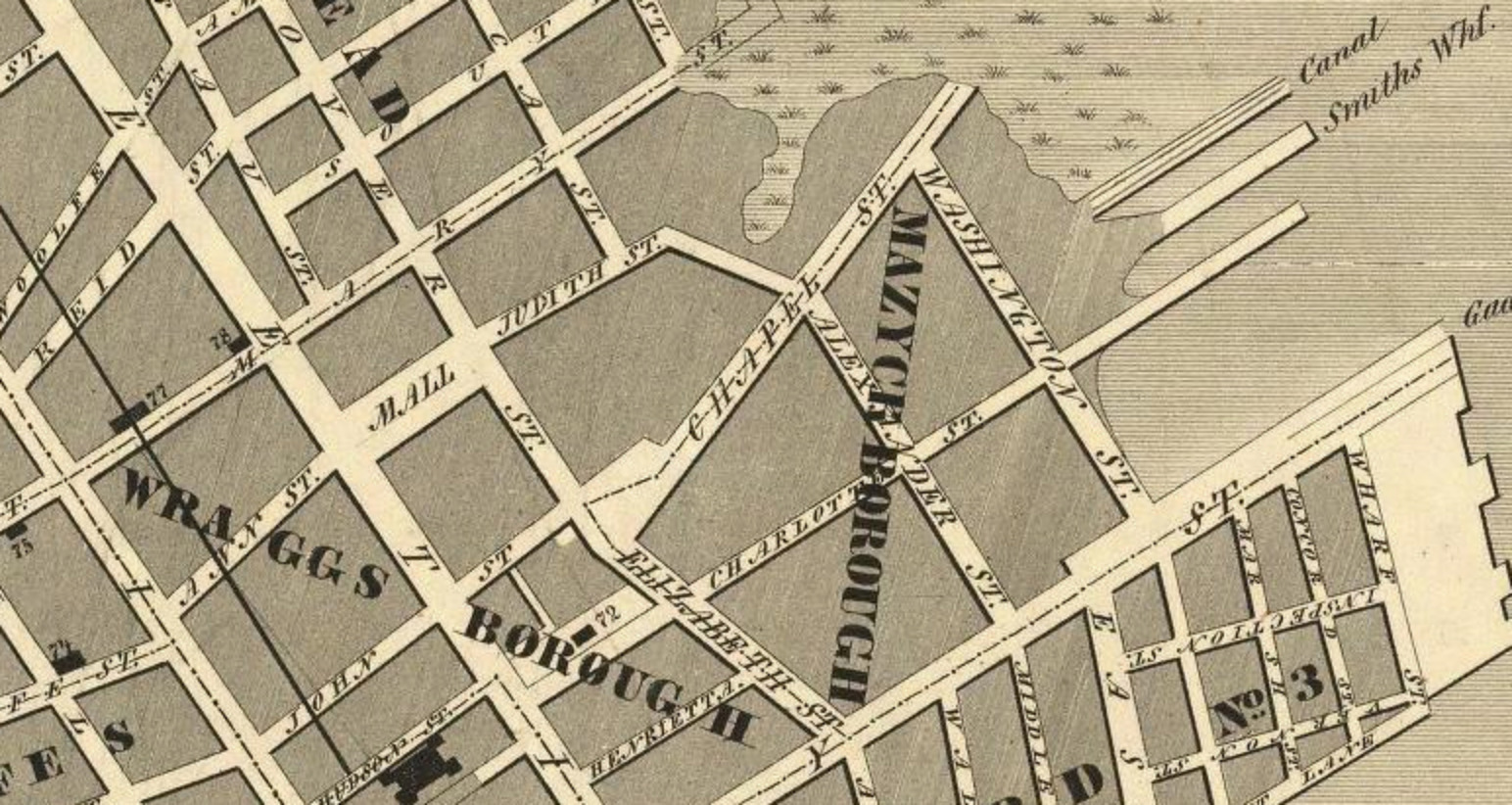

Map of Charleston, 1844, showing Wragg and Mazyckborough. Note the wharves and canal on the cooper River, today the site of the Irish Memorial Park.

Attracted by dock and factory work, nineteenth century Mazyck-Wraggborough became home to German immigrants, enslaved people living out, free people of color, and other working class residents, who lived on short courts; many of these smaller enclaves were replaced by Wraggborough Homes in 1938, although there are still surviving examples of modest wood frame Charleston single houses in the neighborhood, dotted here and there amongst stately mansions with deep, lush gardens.

Bird’s Eye View of Charleston, 1872, showing the Gas Works and Railyards in Mazyckborough.

One of the best examples of these is the Aiken Rhett House, constructed in 1820 and remodeled in the Greek Revival style. The three story brick house is clad in bright ochre stucco and has deep front porches overlooking two brick houses which are the only survivors of Johnson’s Row of seven identical houses that the Aikens rented for income. Aiken Rhett is now a house museum operated by Historic Charleston Foundation and is has some of the most intact slave quarters, kitchens, and carriage houses in the city. Just a block away on Meeting Street is the neighborhood’s other house museum, the Joseph Manigault house, constructed in 1801 in the Adams or Federal style, replete with a bell roofed garden house. It was saved by demolition in the 1920s, and was one of the Preservation Society’s first success stories. The house is next door to the Charleston Museum, which was founded in 1773 and is known as America’s first museum. It features a treasure trove of local artifacts and a natural history collection.

The Aiken Rhett house museum.

Houses in Wraggborough include many styles and eras- Federal period symmetrical brick residences along Charlotte Street, Greek Revival houses of the mid nineteenth century, and wood frame folk Queen Anne Victorian dwellings on Elizabeth and Mary Street. There are even a few corner store buildings, some of which are still businesses like the florist shop at John and Elizabeth, and others that have been turned into residences.

(images 9 and 10). 30 Mary Street, building by contractor John D Murphy in 1884, and renovated as condos. Two units are currently available for sale.; a former grocery turned residence at Elizabeth and Charlotte Streets.

There are several historic churches in Wraggborough that served a diverse population over the centuries. Second Presbyterian Church, a Neoclassical masonry building with a bell tower and full portico, was built in 1811 by the Gordon Brothers, and is the fourth oldest church building in the city. Citadel Square Baptist Church on Meeting Street was designed by Jones and Lee, a noted local firm, in the Romanesque or Norman style with a tall spire that collapsed in the hurricane of 1885 and was completely rebuilt. Francis D. Lee of the same firm designed Fourth Tabernacle Church on Elizabeth Street in 1859, describing it as “perpendicular Gothic [style] peculiarly adapted to our southern climate.” The most famous church today is Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, a Gothic Revival building that is sadly known the scene of the brutal shooting in 2015, but which today stands as a symbol of unity and resilience in the Charleston community.

Second Presbyterian Church and Fourth Tabernacle Baptist are just two of the historic churches in Mazyck-Wraggborough.

Residents in Mazyck-Wraggborough have nearby Marion Square, with its farmer’s markets and festivals, and the restaurants of King Street, just a block away, while within the neighborhood they can enjoy several picturesque parks. Oak lined Wragg Mall near the Rhett house and Wragg Square (in front of Second Presbyterian) were donated to the public by the Wragg family and are as old as the neighborhood itself. The triangular park at the foot of Chapel Street and Tiedeman Park on Elizabeth Street were recently re-landscaped, while the Irish Memorial Park at the foot of Charlotte Street is the newest addition, offering breathtaking views of the Cooper River and Ravenel Bridge.

East Central/NoMo in 1883, with creeks and marshes pushing inland.

Mazyck-Wraggborough is ideal for residents with families in search of large yards but with who want to be near the fun of the city (Buist Elementary is just across the way on Anson Street), and there are also condos in beautifully converted historic homes for those looking for less maintenance without sacrificing character. It remains one of the most desirable parts of the city and truly lives up to its Garden District nickname.

A Sanborn Map from 1902 shows one story cottages for lumber yard workers near Brigade and Meeting Streets.

If you're interested in Charleston Real Estate or simply learning more about the area, contact our team of Charleston Realtors at Empire Properties.

– Wraggborough plat: http://www.archivesindex.sc.gov/Curiosities/Miscellaneous%20Plats/images/L10042No16A.pdf

– Katie Ann Stojsavljevic. Housing and Living Patterns Among Free People of Color in Wraggborough, 1796-1877. Clemson thesis, 2007.

– Plats from Charleston County Register of Deeds

– Christina Butler. Lowcountry at High Tide: A History of Flooding, Drainage, and Reclamation in Charleston, South Carolina. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2020.

– Nic Butler, “Grasping the Neck: The Origins of Charleston’s Northern Neighbor.” https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/grasping-neck-origins-charlestons-northern-neighbor

– Jonathan Poston. Buildings of Charleston. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997.

– Library of Congress photograph and map collections.