As one of the oldest cities in the South, Charleston boasts graveyards and cemeteries full to the brim with the mortal remains of city residents of the past, whose graves are marked with beautiful headstones and mortuary art placed by loved ones. There are also dozens of cemeteries that have been forgotten and are hidden in plain sight below our feet and under later buildings. Leave the city proper and there are beautiful park-like cemeteries and small family burial plots on rural lands to explore. After visiting the graveyards in the daytime, there’s several ghost tour options to further immerse yourself in the spooky season by dark.

Downtown Graveyards

Historic cities like Charleston typically had two types of burial sites- graveyards associated with individual churches, and cemeteries or public burial grounds for “strangers”, “paupers”, or anyone who was not affiliated with a specific congregation. Christina Butler notes in a graveyard article for Kiawah Legends that, “headstones are as varied as the stylistic options of the past, religious denominations and philosophy of the site, and the budget and personal preferences of the interred and their surviving family members. Since there is no stone native to the Lowcountry coast, gravestones had to be imported from the North or even from England, making permanent markers a luxury item in early Charleston. Many burials had wooden markers that have been lost to time. Carving styles changed over time, and cemetery expert Susan McGahee explains, “in the early 18th century, skull and crossbones and hourglass motifs emphasized the inevitability of death and the briefness of life. The stones were intended to remind the living of the uncertain fate of the soul. The Great Awakening, a religious revival that swept the country between 1726 and 1756, emphasized a joyful resurrection for those who repented. By the end of the century, carvings of a winged soul had largely replaced skulls and crossbones.”’

Circular Congregation Church, though not the oldest church building, boasts the oldest surviving headstone in the city, dating back to 1695. Circular’s graveyard has carved slate headstone from the eighteenth century with skull and cross bone motifs and portraits of the person buried in the grave.

Later monuments include Greco-Roman obelisks and marble box tombs from the nineteenth century, and Victorian granite grave markers. Some of the monuments still bear the scars of shell damage from the American Civil War.

Next door on Church Street, St. Philip’s Anglican Church is the oldest congregation south of Virginia, established in 1680. It is unique because it has a graveyard next to the church and a cemetery because Church Street bisects the property. Col. William Rhett (best known for capturing the pirate Stede Bonnet), vice president and senator John C. Calhoun, Declaration signer Edward Rutledge, and Charleston Renaissance author Dubose Heyward are among the famous South Carolinians interred there.

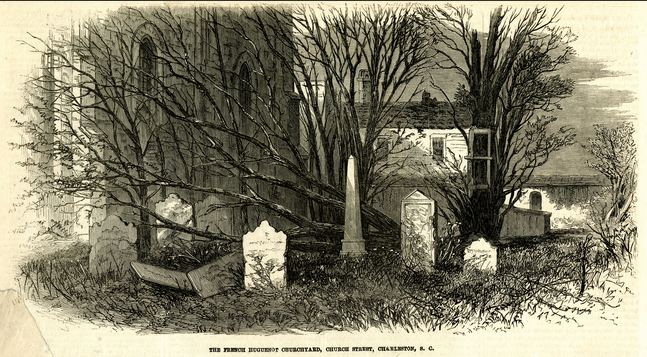

At St. Mary’s Catholic Church on Hasell Street, taphophiles can find stones in French, from some of the earliest congregants who came to Charleston when they were displaced from St. Domingue during the Haitian Revolution. The French Huguenot Church on Church Street also has stones in French for its Protestant congregants.

South of Tradd Street on Church Street is the oldest Baptist Church in the South, First Baptist Churchyard. There is a beautiful portrait in slate carved by John Stevens (of Newport, Rhode Island) to memorialize Abigail Baker, who died of yellow fever in 1797. Visitors will also notice numerous headstones leaning against the side of the church; these oddly placed stones where moved when a new parish building required reinternment of several early burials. Historic tomb inscriptions here range from biblical quotes to biographical sketches for prominent citizens to the downright unique, like Sarah Bird’s stone at First Baptist Church, “who departed this life on December 2nd, 1819, ages 74 years, 11 months, 14 days. Her death was occasioned by an accident being run over by a loaded wagon and a team of horses shortly after leaving her home in perfect health. Alas, never more to return to it, being carried to a friend’s house where she breathed her last.”

St. Michael’s Church at the intersection of Meeting and Broad Street is the oldest church building in the city, begun in 1752, and has several important people interred in its graveyard, including John Rutledge and Charleston Cotesworth Pinckney, signers of the U.S. Constitution. Visitors are usually intrigued by the “bedstead tomb”, a curious wooden grave marker shaped like a headboard. It marks the final resting place of Mary Ann Luyten, who died aged 29 and whose loving husband had cared for her for years when she was bedridden after falling from a horse. The original marker is now at Charleston Museum to protect it from the elements.

The Unitarian Church graveyard on Archdale Street is popular for its picturesque and natural landscaping, where plants wind around ancient headstones along the brick paths. This natural approach stands in contrast to more rigidly manicured graveyards like St. John’s German Lutheran just next door.

Every neighborhood has historic church burial grounds, which are usually open to the public, and there are even markers in public spaces, like that for Stede Bonnet the pirate and his crew, which is located in White Point Garden. As criminals, Bonnet and his men did not receive a final resting place in a prestigious Charleston graveyard. They were instead buried on the shore between high and low tide line, in what is today part of the park.

Hidden in Plain Site

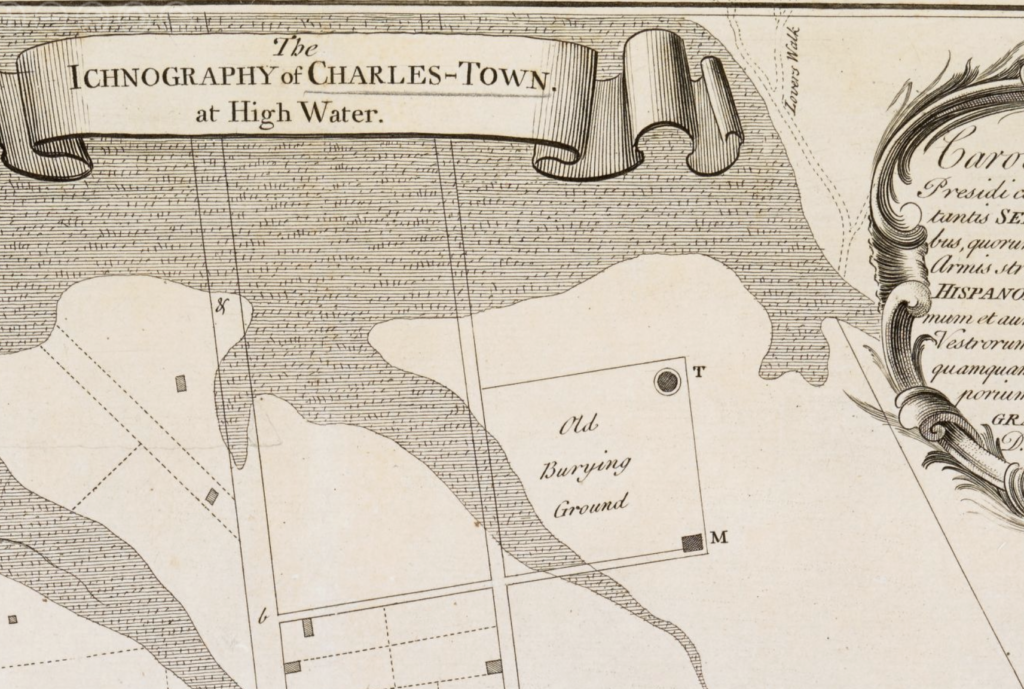

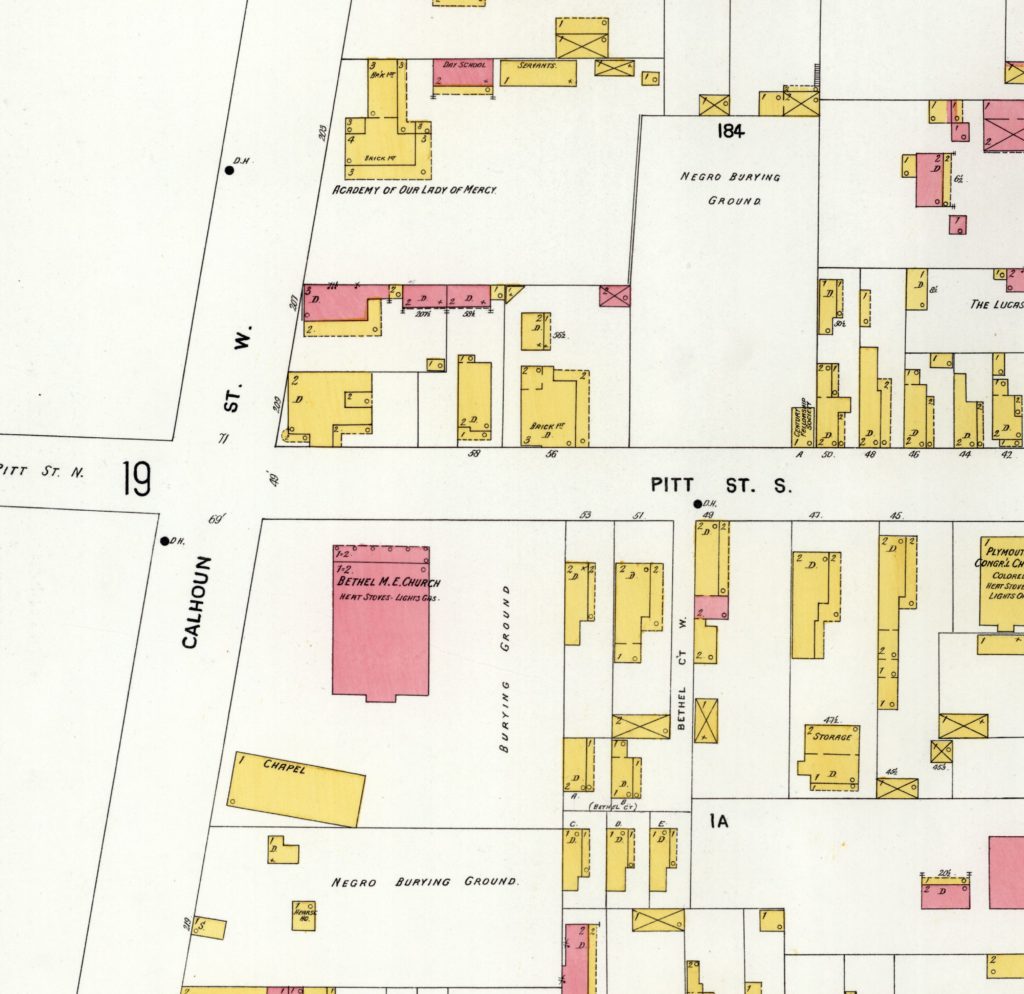

As churchyards filled, Charlestonians created “overflow” cemeteries on the Neck of Charleston. Historian Nic Butler explains, “Among the largest, oldest, and most densely populated graveyards in Charleston County are the forgotten public cemeteries established within the urban boundaries of the City of Charleston. Transient Christians, including sailors and other visitors commonly called “strangers,” who died within the town might have been buried within the graveyard of any one of the local churches or within the designated public burial grounds.” Many of these were forgotten over time and in turn were developed and are now underneath various historic neighborhoods. For example, over 13,000 people were interred on the public burial ground and “Negro burial ground” on a few acres in Harleston Village where the Old District Jail lies today. For more details, visit https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/forgotten-dead-charlestons-public-cemeteries-1672-1794.

The city seized several cemeteries for back taxes as the churches or burial societies who previously maintained them went defunct in the twentieth century. A quick look at the 1902 Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps show several on the upper peninsula, and the College of Charleston’s Addlestone Library on Calhoun Street is also on former burial ground.

Cites of the Dead

Magnolia Cemetery was created in 1850 on the banks of the Cooper River on a former rice plantation called Magnolia Umbra and is a southern gothic gem. The Charleston Courier reported on the Magnolia’s construction in 1850 that, “the grounds are already enclosed; the main avenues, embracing an extensive ride, are guarded and constructed; the chapel, which is of a Gothic style, is in rapid progress of erection; the lakes are to be supplied with water from the Cooper River. We feel great interest in the success of this enterprise, believing it will advance the best interests of the community.” Harper’s Monthly described Magnolia as “a very lovely city of the silent.”

In the eclectic Victorian age when Magnolia was constructed, some clients desired funerary art that referenced the ancient classical world- obelisks, Greek temple forms, and even Egyptian motifs, while others sought Gothic designs and wrought iron fencing for their family plots. The Vanderhorsts were buried at Magnolia Cemetery in an elaborate Egyptian Revival brownstone mausoleum designed by architect Francis D. Lee. Other important tombs at Magnolia include the stone pyramid mausoleum of W.B. Smith, and Colonel William Washington’s monument, a fluted Doric column with a rattlesnake slithering up the base, which was designed by famous Greek Revival architect Edward Brickell White.

Next door to Magnolia, St. Lawrence Catholic Cemetery, with its intricate wrought and cast-iron cross monument at the entrance, opened in 1854 on the adjacent marsh front lot, and several other cemeteries cropped up along Cunnington Road that led to Magnolia and St. Lawrence. John P. Grace (1874-1940), the city’s first Catholic mayor, is buried there, along with Irish and Italian Charlestonians, priests, and nuns with the Our Lady Mercy.

Country Burials

Rural cemeteries are as varied as the size of the congregations or families that created them. Some are well maintained while others are so overgrown that even the most dedicated descendant would struggle to relocate the site. Lowcountry burial grounds were often segregated, with slave owner and enslaved on different locations on a plantation. The white burial sites were formal, walled plots, while the enslaved had their own unique funerary customs.

“Ghost Island” is an intriguing example of a now-defunct private family burial site. The Lining family built a large stone vault for their deceased relatives on a small island in the Ashley River, which sadly was desecrated in the late nineteenth century by vandals with a morbid streak who wanted to see what was in the historic coffins, so the remains have since been interred elsewhere. For the full story, check out https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/ghost-island-desecration-ashley on the Charleston Time Machine at the Charleston County Public Library.

African American burial sites often had impermanent markers, although it was common practice in the Gullah community to leave small trinkets on the graves of one’s ancestor. Enslaved people brought from the Kongo and Angolan ports of West Africa carried their Bakongo culture with them to the Lowcountry, including the belief in one God and afterlife in a spirit world. Susan McGahee explains, “to the Bakongo, graves were important mediums for communication with the spirits of the dead. They decorated graves with personal belongings of the deceased.” Shells, pitchers, jugs, vases, lamps, candles, and shiny objects are the most common burial offerings in coastal South Carolina. Drayton Hall plantation has an intact cemetery of the enslaved that is open to visitors, and there are other lesser known examples throughout the Lowcountry, next to subdivisions or tucked along the marshes.

Guided tours ‘behind the scenes’

For a deeper dive, Bulldog tours (https://www.bulldogtours.com/tours/ghost) offers several walking tours that take guests into the cemeteries and haunted spaces for an up close spooky experience. Tours options included the USS Yorktown ghost tour (on a World War Two era aircraft carrier), the Spirits of Magnolia cemetery tour, Ghost and Dungeon tour (into the depths of the provost dungeon below the 1771 Old Exchange building), a Haunted Pub Crawl, and the ever-popular Haunted Jail tour, inside what is alleged to be the most haunted building in the city with a dark history as a district jail that is located on the site of a large historic burial ground. The Ghosts of Charleston walking tour (https://www.buxtonbooks.com/ghosts-of-charleston) leaves from Buxton Books every night and takes visitors into the Unitarian graveyard. Old South Carriage (https://oldsouthcarriage.com/carriage-tours/haunted-carriage-tour/) offers evening and twilight haunted carriage rides past Circular Congregational graveyard and the Old Exchange. For something completely different and “without all that walking- not in these heels” try the new Death is a Drag experience (https://charlestonculinarytours.com/food-tours/death-is-a-drag/) where queen Kira Lee shares R rated true Charleston ghost and horror stories over desserts and spooky themed cocktails. The Lowcountry’s graveyards and ghost tours are open year round, not just for Halloween!

Contact Charleston Empire Properties today to learn more!

Sources:

- Butler, Christina Rae. “Hallowed Ground.” Kiawah Legends Magazine. 33 (Spring 2019), 122-125.

- com, cemetery inscriptions for Charleston County.

- Hicks, Brian. “The Story of the First Memorial Day, a Holiday Born in Charleston.” Post and Courier, 26 May 2019.

- Karpiel, Frank. Charleston’s Historic Cemeteries. Charleston: Arcadia, 2013.

- Magnolia Cemetery National Register Nomination, 1978.

- McGahee, Susan H. and Mary W. Edmonds. South Carolina Historic Cemeteries: A Preservation Handbook. Columbia: SCDAH, 2006.

- Parker, Adam. “Discovering the dead: Gullah society takes on preservation of black burial grounds in Charleston.” Post and Courier. 17 August 2017.

- Philips, Ted. City of the Silent: The Charlestonians of Magnolia Cemetery. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2010.

- Trinkley, Michael. The Silence of the Dead: Giving Charleston Cemeteries a Voice. Columbia: Chicora Foundation Research Series 67, 2010.

- Butler, Nic. “Ghost Island: Desecration on the Ashley”. Charleston Time Machine at CCPL. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/ghost-island-desecration-ashley (October 2022).

- https://charlestonculinarytours.com/food-tours/death-is-a-drag/

- Butler, Nic. “The Forgotten Dead: Charleston’s public cemeteries, 1794-2021.” Charleston Time Machine at CCPL. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/forgotten-dead-charlestons-public-cemeteries-1794-2021(October 2021).

- Butler, Nic. “The Forgotten Dead: Charleston’s public cemeteries, 1672-1794.” Charleston Time Machine at CCPL. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/forgotten-dead-charlestons-public-cemeteries-1672-1794(October 2021).