The West Ashley Greenway, which runs for eight miles through the heart of Saint Andrew’s Parish and greater West Ashley, is a free recreational amenity and one of the best kept secrets in the Charleston suburbs, boasting beautiful views, well maintained trails for jogging, walking, or cycling, and with an interesting backstory dating back centuries.

The trail begins at South Windermere Shopping Center off of Folly Road near Wappoo Creek and continues to Johns Island past several subdivision and luxury apartment complexes- and some rural sites- between the Stono and Ashley Rivers, with several access points and places to park along the trail.

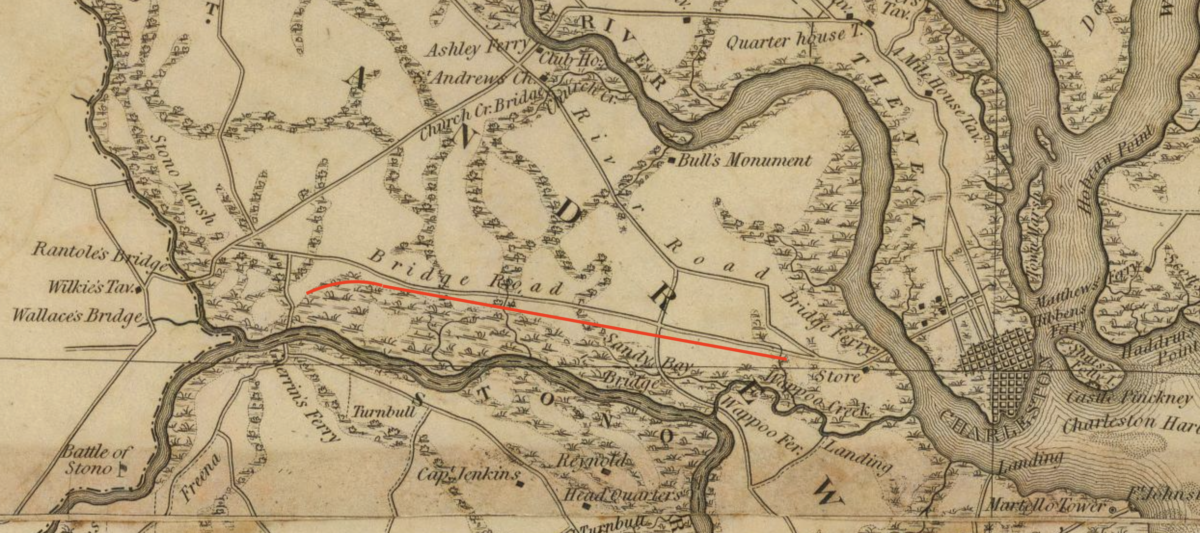

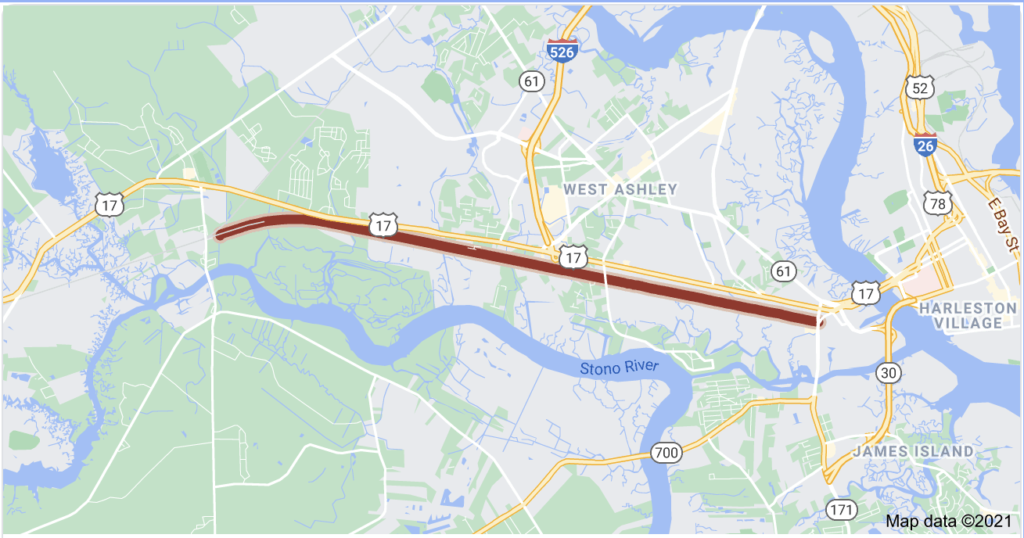

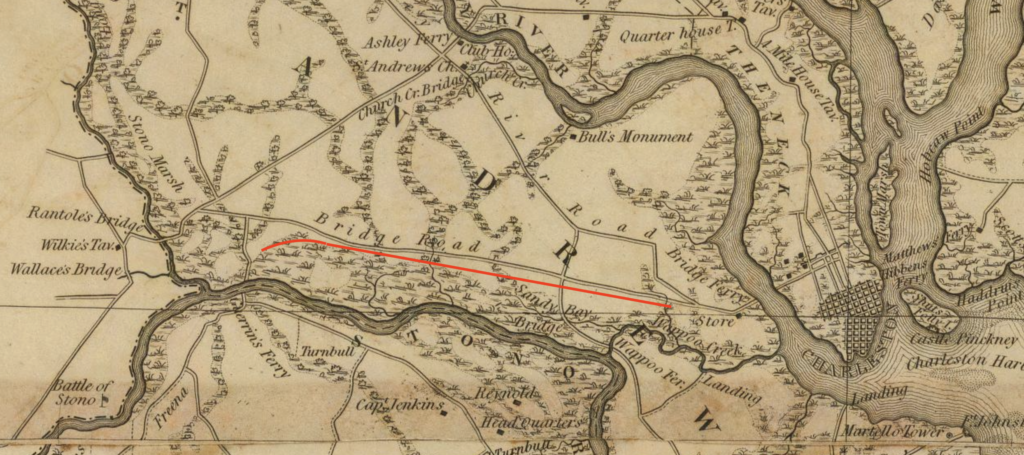

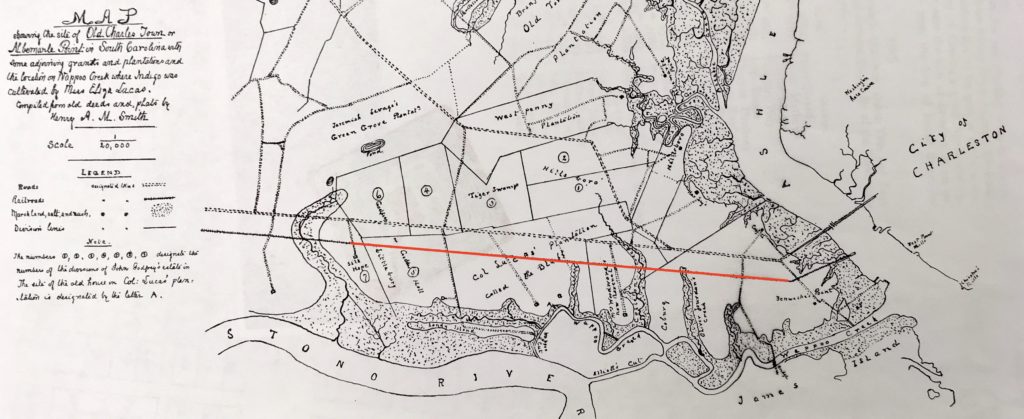

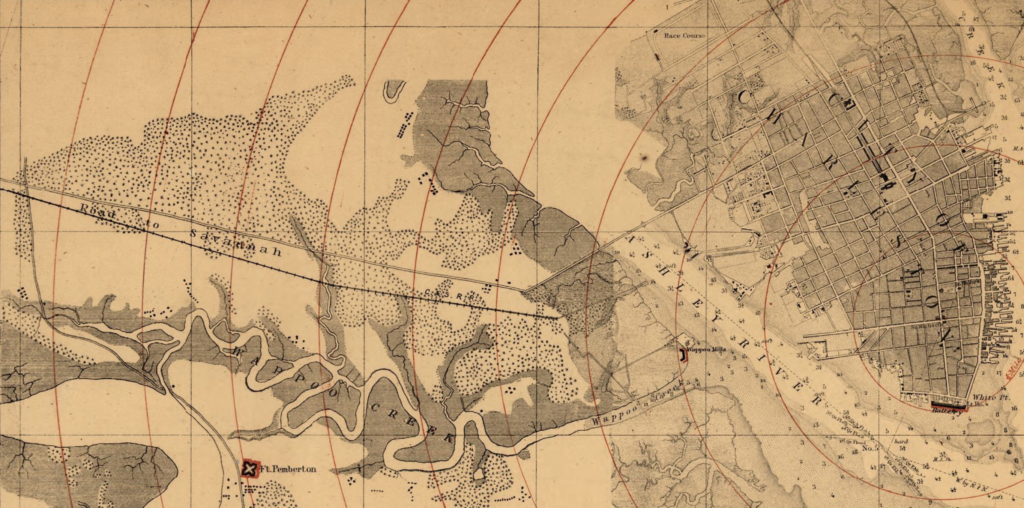

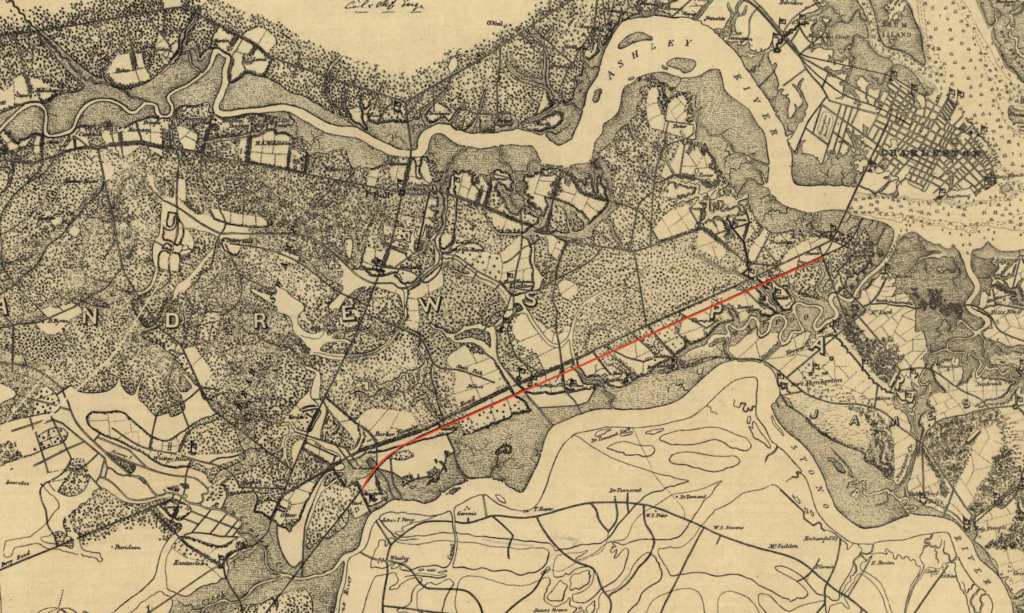

The West Ashley Greenway in Charleston, SC runs on a linear trajectory that follows the former path of the Croghan’s Branch of the Atlantic Coastline Railroad, which chugged its way through the plantations of St. Andrew’s Parish that had already been in use for over a century by the antebellum steam era. According to historian H.A.M. Smith, Fenwick’s Point lay near the start of today’s trail at Wappoo Creek. Oliver Jordan’s Creek and Colleton’s Creek framed Mrs. Woodward’s estate, and west of that was the large Bluff Plantation of the Lucas family. John Lucas came to St. Andrew’s from Antigua and later passed the plantation to his son George Lucas; whose daughter was the famed Eliza Lucas Pinckney who experimented with indigo production in the colonial era. Godfrey’s plantation (also called Quarterman and Geddes Hall) was next, bounded by Littlebury, with Silk Hope Plantation at the John’s Island end of the today’s trail.

The Atlantic Coastline Railroad was begun in the 1830s and became an important thoroughfare from Charleston to Savannah for steam powered rail engines and cars that carried passengers, livestock, cotton, and wholesale goods. Today, parts of this historic route have been transformed into the West Ashley Greenway in Charleston, SC, a beloved recreational trail. During the American Civil War, the Charleston to Savannah line became an important logistical rail for the Confederacy, transporting civilians, troops, ammunition, and fuel for the war effort. Parts of the line were badly damaged by the Union forces, who recognized the strategic importance of rail shipping (historians often attribute the Confederate loss in part to the lack of standard gauge and widespread rail in the American South.)

Joseph Taylor purchased and rebuilt the line in the late 1860s, and it was operated by Atlantic Coastline, CLX, and other companies to transport crops and livestock. On each side of the rail line from St. Andrew’s Parish into Johns Island, passengers in the early twentieth century would have seen “acres upon acres” of “truck farm” produce- cabbages, potatoes, carrots, beats, and tomatoes. A 1908 article described, “truck lands [that] lie along the shell road . . the facilities for shipping truck at St. Andrew’s are excellent, as a branch of the Coast Line, having Johns Island Station on the main line as its northern terminus, runs through this fine farming country to the Wappoo Bridge. On this West Ashley Greenway trail are located packing and shipping sheds at frequent intervals, and here the cars are loaded to their capacity and in charge of a shifting engine are conveyed to the main line, where the through freight trains are made and rushed through to New York without delay. Some of the planters in this section are Messrs Croghan, Voorhes and Ravenel.”

Seaboard Coast Rail took over the line but abandoned it in 1981, following the sad fate of so many other American lines in the late twentieth century. Following the successful “Rails to Trails” movement of converting disused rail lines into public parks and amenities (such as the Highline in New York City), Charleston decided to create the West Ashley Greenway in Charleston, SC. According to the City of Charleston’s Special Projects Coordinator Mathew Compton, “Charleston Water Systems (then CPW) acquired the property in 1984-85 for use as a utility corridor. The City of Charleston entered into lease discussions with them in 1988-89, and began work on the initial unpaved trail in late 1989. Our records show that the facility was opened for public use in 1990. The original intent was to leave the facility unpaved, but that limits the trail utilization to exercise only, omitting convenient commuter cycling use. The first paved segment was opened in 2007.” . Sports fields and a historic marker for the ACL Croghan Rail line mark the beginning of the trail at Albemarle Road. The West Ashley Greenway in Charleston, SC continues west at South Windermere Shopping Center, which offers trail parking and several cafes and a pet shop to stock up before the trek. The West Ashley Greenway trail passes next through several new subdivisions including Byrnes Downs along the west side of US 17, which was once part of the Coburg Dairy Farm; “Bessie” the Coburg Cow in front of the Harris Teeter at Coburg Road is the best visual reminder of this stretch of West Ashley Greenway in Charleston, SC’s agricultural past. The dairy farm opened in the 1920s but later moved to a new facility further from the city, leaving the 1950s neon sign and famous cow behind as a landmark.

To the north of the Greenway, the West Ashley Greenway trail way begins in the Ashleyville neighborhood along the Ashley River, before continuing southwest past midcentury neighborhoods East Oak and West Oak Forests before terminating just above the longer rail trail Greenway at Wappoo Drive.

Higgins Pier, named for African American educator and community leader Leonard Higgins, marks the beginning of one the “blue trails” of the upper Greenway, which are designed for hikers on the trail to enjoy views of West Ashley Greenway in in Charleston, SC’s many waterways. The West Ashley Greenway trail does not currently connect to the longer original Greenway, but they nearly converge at Wappoo Drive before the Greenway continues for several more miles toward Johns Island.

The West Ashley Greenway in Charleston, SC path alternates between asphalt paving and hard packed dirt and the whole length is well maintained for strollers, bicycles, and pedestrians traveling by foot. Past Farmfield Drive, the West Ashley Greenway trail passes the Charleston Tennis Center (with restrooms for trail goers) and continues westerly through alongside new communities and marshes stemming from small tributary tidal creeks of the Stono River. There is additional parking and trail access at Carolina Bay Drive nearer the western end of the Greenway, which ends at McLeod Mill Road on Johns Island. There are plans to continue the rail trail further onto the islands in the future.

Savor the natural beauty along the West Ashley Greenway in Charleston, SC, a haven for outdoor enthusiasts and nature lovers. Picture yourself living just moments away from this green space, where adventure and tranquility coexist.

With Charleston Empire Properties, finding a home near this lush recreational area is within reach. Contact us today to begin your search for the perfect home for sale in Charleston, SC offering both outdoor access and comfort.

- “history of the West Ashley greenway.” Charleston Today. 25 May 2020. https://chstoday.6amcity.com/west-ashley-greenway-history-charleston-sc/

- Charleston Parks Conservancy. “West Ashley Greenway.” https://www.charlestonparksconservancy.org/park/west-ashley-greenway

- City of Charleston/ Parks Conservancy. West Ashley Greenway Masterplan.

- Rails to Trails Conservancy, “History of Rail-Trails”, https://www.railstotrails.org/about/history/history-of-rail-trails/

- South Carolina Picture Project. “The Coburg Cow.” https://www.scpictureproject.org/charleston-county/coburg-cow.html

- News and Courier. “Of Cabbages and the Cabbage King.” Apr 6, 1908.

- Christina Butler. “East and West Oak Forest: West Ashley’s Hottest Midcentury Neighborhoods.” July 2020. https://charlestonempireproperties.com/east-and-west-oak-forest-west-ashleys-hottest-midcentury-neighborhoods/

- Henry Augustus Middleton Smith. “Old Charles Town and Its Vicinity”, South Carolina Historical Magazine, Vol 16. no 2. (April 1915), 49-67.