Charleston is renowned for its beautiful architecture, and perhaps the most impressive and culturally important examples are the city’s sacred spaces. As an English colony, the earliest congregation was Anglican, but they were quickly followed by Baptists, Unitarians, Huguenots, Lutherans, Congregationalists, Jews, and as religious freedom expanded after the American Revolution, Catholics. Below we’ll provide a tour of several noteworthy churches that are open for visits, or service, if you’re moving to Charleston and looking for a new congregation.

As a port city in the colonial Atlantic world, Charlestown had a diverse population from its founding, which is reflected in the comparably vast number of denominations that worshiped here from the earliest days. Enslaved Africans and Native Americans had their own sacred traditions that are lost to time or were melded with European Christian practices to create new faiths like the African Methodist Episcopal church. Sephardic Jews also came to early Carolina, along with Quakers and Huguenots and almost every other Christian denomination being practiced in eighteenth century Europe, except for Catholics, who were not welcome in the British colony.

Compared to New England colonies founded for religious reasons, South Carolina was relatively liberal in allowing people to establish meeting houses because it was a proprietary colony established as a money-making venture. The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina Colony stated that, indigenous persons, “Jews, heathens, and other dissenters from the purity of Christian religion,” should be welcomed and given “an opportunity of acquainting themselves with the truth and reasonableness of its doctrines [of the Anglican faith]”. A measure of tolerance was a good way to encourage Europeans to immigrate. For example, when the Huguenots (French Calvinist protestants) were exiled from France, some settled in Charlestown alongside the English.

Anglicanism, however, was the state-backed religion, and all settlers regardless of faith paid taxes to construct and support the Anglican congregations like St. Philips and St. Michaels. It’s important to remember that religious choices had political implications, and that “the legal and political landscape of early South Carolina became an extension of the prejudices and discriminatory practices that characterized English culture of the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries.”

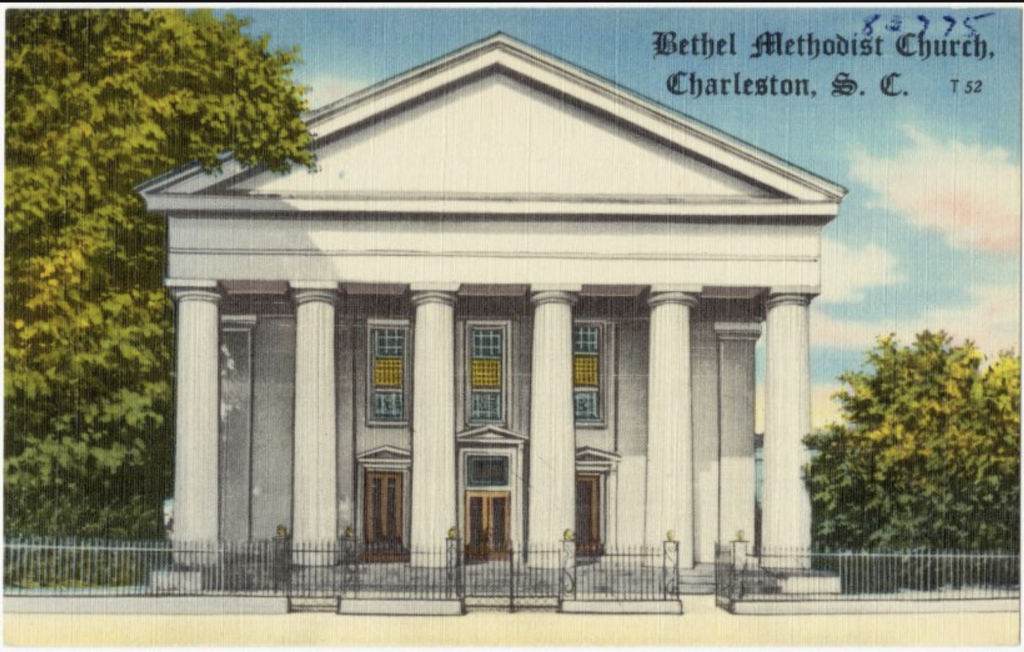

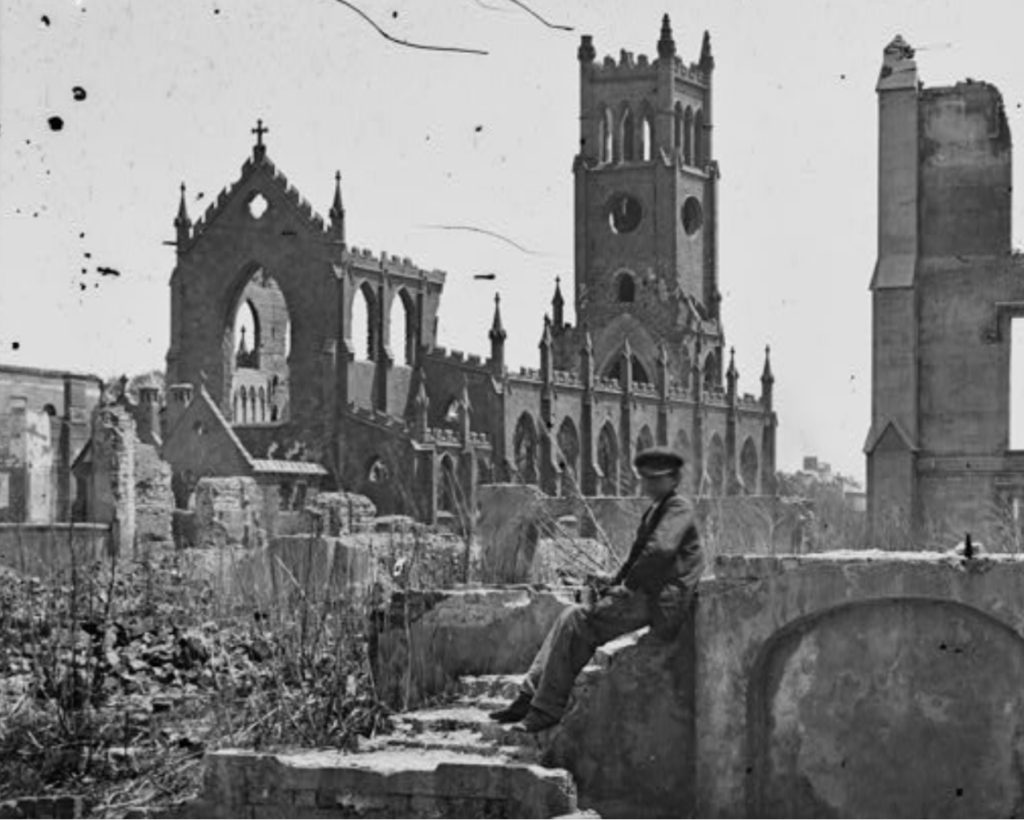

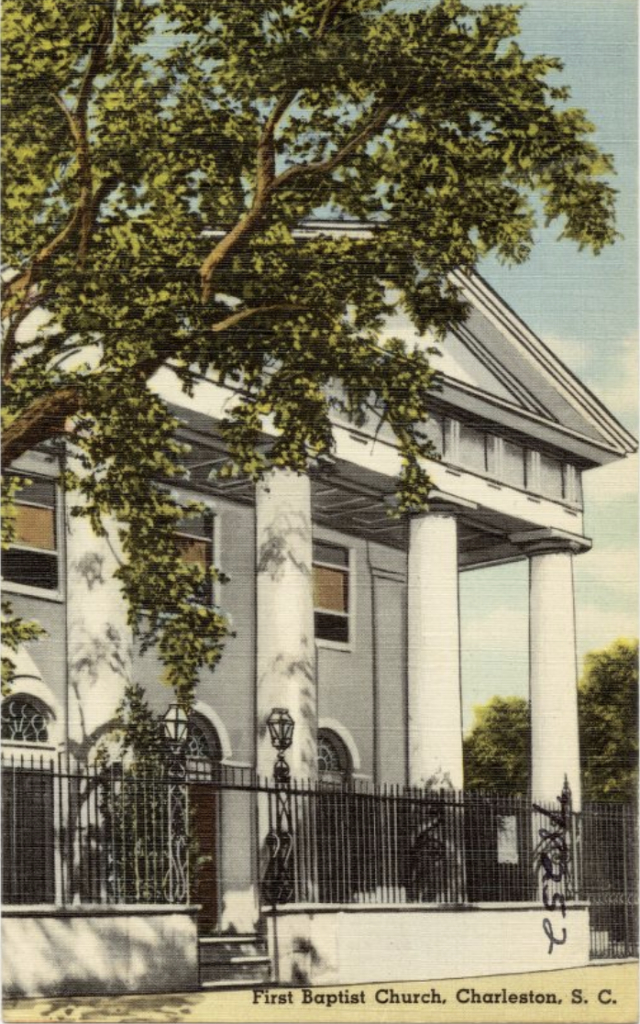

Charleston’s churches reflect changing architectural style in the city over time. The earliest buildings were either simple frame buildings (like the lost Methodist meeting house) or grand Georgian churches, such as St. Michael’s, which reflected the work of the latest architects in London. By the early nineteenth century, neoclassical and Greek Revival buildings became popular, like St. Johannes Church, designed by Edward Brickell White in the Roman Revival style or First Baptist Church by famous architect Robert Mills. Gothic Revival style was also popular throughout the nineteenth century for churches, especially for Roman Catholic congregations. A beautiful later example is St. John the Baptist Cathedral, completed in 1907 of Connecticut brownstone, which replaced the earlier Gothic style St. Finbar Cathedral, which burned in the great fire of 1861.

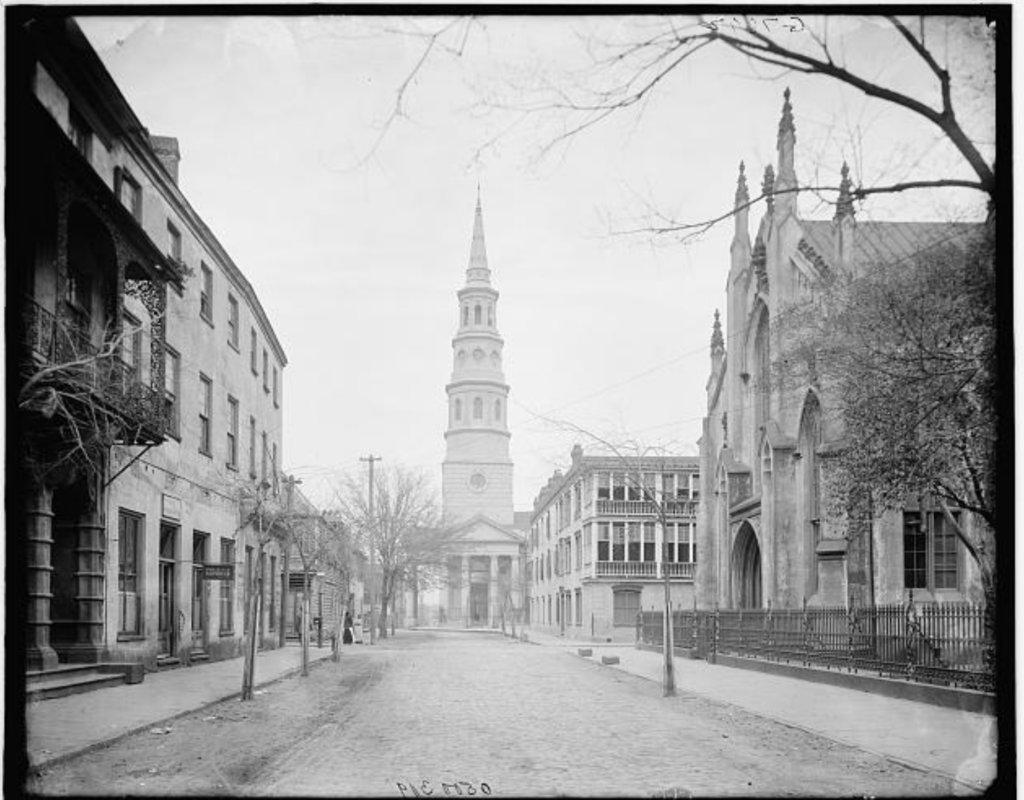

The best way to see Charleston’s most famous early churches, and the ones most often open to the public, is to stroll down Meeting Street (so named because of an early religious meeting house where Circular Congregation Church sits today), and aptly named Church Street, which runs parallel to Meeting Street and gets is name because the road bends around historic St. Philip’s Church. First Scott’s Presbyterian Church at Meeting and Tradd Streets dates to 1814, with a congregation founded in 1731. The church donated their bells to the Confederate cause during the Civil War and remained silent until the congregation purchased a bell cast in England in 1814 (to reflect the church’s construction date) and installed it in 1999. St. Michael’s is the oldest surviving church building in the city, begun in 1752 and standing proudly at the intersection of Meeting and Broad Streets. Down the block is Circular Congregational Church, completed in 1892, is the fourth building on the site. The congregation of “dissenters” dates to 1681, and the graveyard hosts the oldest surviving headstone in the city, circa 1695. Circular graveyard is open every day and the church is open on occasion, always for services, and on select evenings for concerts in the vaulted Richardsonian Romanesque interior.

Turn onto Cumberland Street and then onto Church Street to see St. Philip’s Anglican Church, which is the oldest congregation, founded in 1680. The current Georgian Revival building dates to 1838 and replaced an earlier building lost to fire. A block south is one of the only active French Huguenot churches left in the United States. The current building is Gothic Revival with cast iron pinnacles and spires, but the interior is crisp and bright. Legend states that the previous building was known as the “church of the tides” because Queen Street was formerly a small tidal creek and some parishioners came to the church by boat. South of Broad Street is the first First Baptist Church in the South. The current Robert Mills building has a grand classical portico.

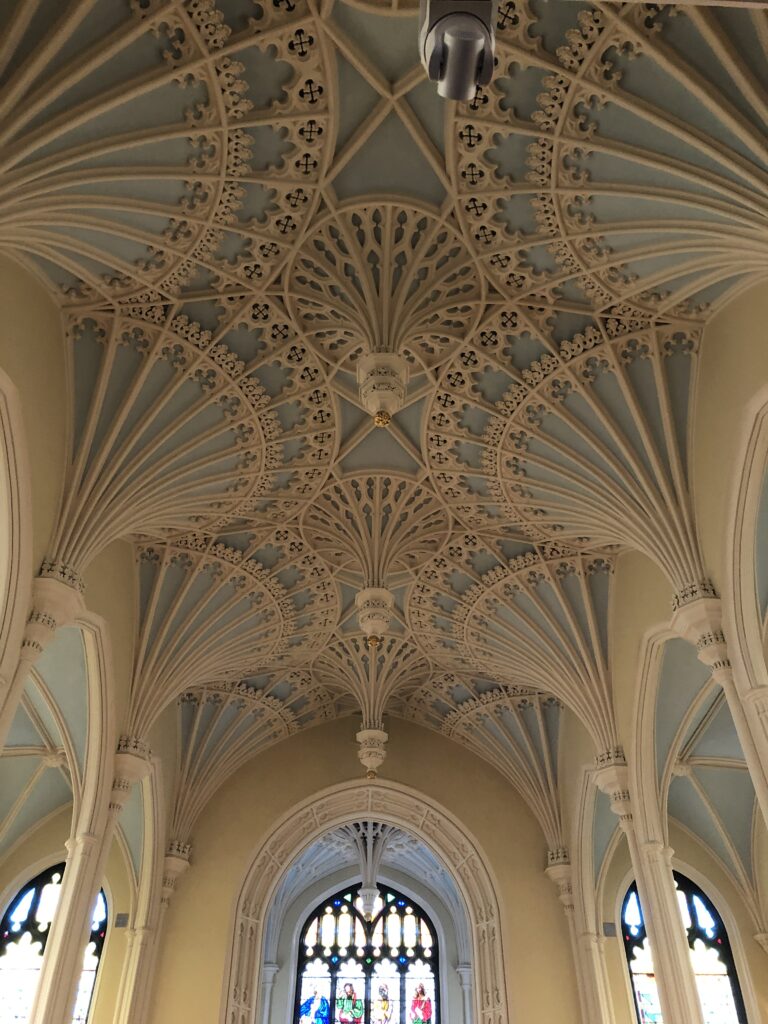

Archdale Street a few blocks away is home to two other important churches: Unitarian and St. John’s Lutheran. The Unitarian Church is a perpendicular English Gothic building with elaborate plaster fan vaults above the nave. The congregation began in 1772 as an outgrowth of the Circular Church and the building’s construction was halted by the onset of the American Revolution. The graveyard is open daily and is known for its romantic and natural plant life intertwined with ancient headstones.

St. John’s Lutheran directly next door was built in 1818 and retains its original forged iron entry gates. The congregation was founded in 1734 and is the oldest Lutheran entity in the city, founded by German immigrants.

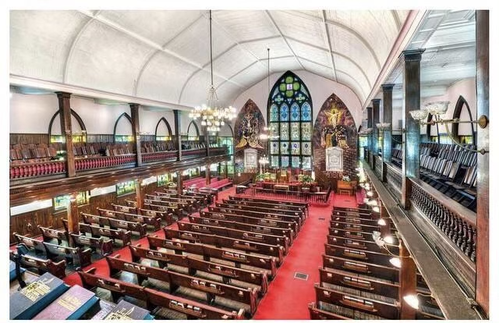

To the north, Hasell Street is home to Greek Revival style KKBE Synagogue. Their website states, “Founded in 1749, KKBE is one of the oldest congregations in America, and is known as the birthplace of American Reform Judaism. Our sanctuary is the oldest in continuous use for Jewish worship in America, but Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (KKBE) is more than just a house of worship. We are a vibrant, inclusive and caring congregational family.” St. Mary’s Catholic just across the street is the oldest surviving Catholic church building in the city, constructed after the 1838 fire destroyed the earlier building, and the oldest Catholic congregation, founded in 1789 when Catholics were allowed to practice their faith legally for the first time in South Carolina in the early federal era.

Though the African Methodist Episcopal faith was founded by in 1816, enslaved people had limited religious freedom and were typically not allowed to worship in groups unattended after the Denmark Vesey slave insurrection trial of 1822. Some worshiped in white congregations or prayed on their own. After emancipation, freed people created their own congregations and raised funds to build new buildings or purchased earlier churches for their own use. Mother Emanuel AME Church on Calhoun Street was founded in 1865. Construction on the soaring white Gothic Revival building that stands today began in 1891. Sadly, Emanuel is now internationally known because nine parishioners were senselessly murder by white supremacist Dylan Roof in 2015, who was subsequently tried and found guilty. People come from around the nation to pay respects and leave memorials at Emanuel, which is still active and welcoming new members.

As the city expanded and its population grew, evermore churches were established in the historic suburbs north of Calhoun Street. These churches are lesser known to tourists but are still active and often boast beautiful buildings and graveyards, making them worth the walk. Just a few, grouped by neighborhood, include:

Ansonborough: St. Johannes Lutheran; St. John’s Reformed Episcopal (built in 1850 as a Catholic church); Redeemer Presbyterian on Wentworth Street.

Wraggborough: New Tabernacle fourth Baptist (Gothic Revival, built 1859); Second Presbyterian Church (1811); Citadel Square Baptist (founded as an overflow for First Baptist, built in 1856, steeple replaced after the hurricane of 1885).

Cannonborough/Elliottborough/Radcliffeborough: St. Patrick’s Catholic (Gothic Revival building from 1887, congregation 1838. St. Philip Street); St. Luke and St. Paul Episcopal Cathedral (neoclassical, built 1810 by the Gordon Brothers, who also built Second Presbyterian. Cannon Street). St. Mark’s Episcopal (founded in 1865 by freedmen, located on Thomas Street); St. Mathew’s German Lutheran (a soaring Gothic Revival building on Marion Square)

East Side: St. John’s Chapel (founded in the 1830s as a mission church by St. Michael’s, to administer to immigrants and working-class Charlestonians in Hampstead neighborhood); St. Luke’s Reformed Episcopal (Carpenter Gothic, Nassau Street); Greater Beard AME church (Hanover Street, near the site of the first AME Church in Charleston which was closed after the Vesey Rebellion).

There are many more churches throughout the city, just waiting to be explored.

Sources:

- Nic Butler. “The Myth of the Holy City.” Charleston Time Machine. https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/myth-holy-city

- Louis Nelson. Beauty of Holiness: Anglicanism and Architecture in Colonial South Carolina. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2009.

- Jonathan Poston. Buildings of Charleston. Columbia: USC Press, 1996.

- James Underwood and W. Lewis Burke. The Dawn of Religious Freedom in South Carolina. Columbia: USC Press, 2006.

- Clifford Legerton. Historic Churches of Charleston. Charleston: Legerton and Co., 1966.

- George C. Rogers. The Churches of Charleston and the Lowcountry. Columbia: USC Press, 1994.

- Nic Butler. “The Men Who Built St. Michael’s Church, 1752-1754.” Charleston Time Machine.https://www.ccpl.org/charleston-time-machine/men-who-built-st-michaels-church-1752-1754

- Jacoby, Mary Moore, ed.The Churches of Charleston and the Lowcountry. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1993.

- Sarah Fick. “Circular Congregational Church.” South Carolina Encyclopedia. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/circular-congregational-church/

- Bernard E. Powers Jr. “Slave Religion.” South Carolina Encyclopedia. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/slave-religion/

- https://www.kkbe.org

- https://motheremanuel.com