Charleston might not get the full spectrum of fall leaf colors, but it doesn’t get snow either, so late fall and winter are the perfect time to get outside and explore the Lowcountry’s cooler weather traditions, from oyster roasts to beach walks to hiking.

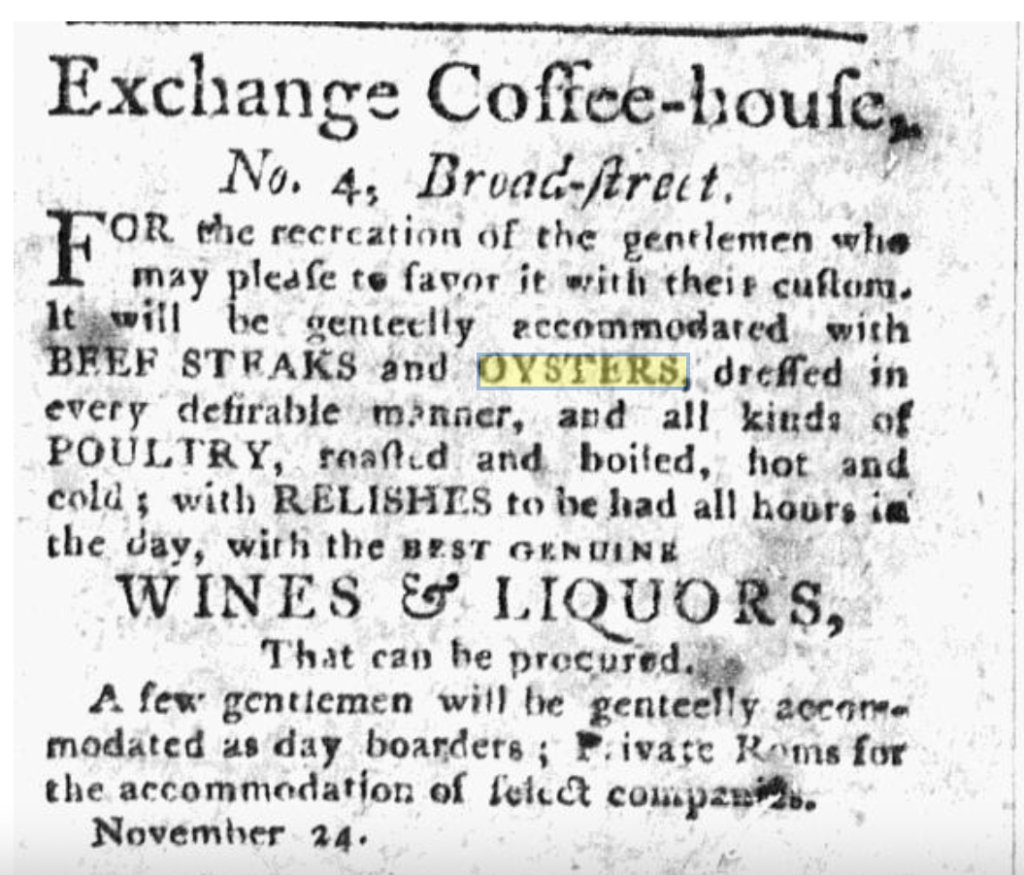

As the weather turns cooler, the mosquitos die, the humidity abates, and the Lowcountry becomes awash with the golden hues of autumn marsh grass, and as the waters cool, oyster season begins. Local oysters are salty and sweet and delicious raw, fried, steamed, or in a po boy sandwich. SCDNR explains that, “the South Carolina oyster fishery is based entirely on the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica. Although other oysters are grown on the west coast, no other commercially important oyster species occurs on the east coast. The oyster is one of the most popular local seafoods. It is readily available and can be served in a variety of appetizing ways. Oysters are not only palatable, but also contain a number of vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates and proteins.”

There is an age-old adage that advises seafood connoisseurs to only eat oysters on months that contain “r”- November, December, January, etc.- essentially, the cold months of the year. The justification for the rule was that oysters were often unsafe to eat in the warmer months and could lead to food poisoning. Summer is also spawning season and letting oysters procreate is necessary to ensure a large, stable population for the next year.

Though farmed oyster practices and refrigeration diminish the “r” month concerns, there’s still good reason to wait for winter. Lowcountry boil (a one-pot delicacy with shrimp, corn, sausage, potatoes, Old Bay seasoning and other spices) and roasted oysters are easier to prepare outdoors, so fall and winter are the best season for the feasts. Fresh caught oysters are roasted on large sheets of metal or pans over open flames, then shoveled still-steaming onto large tables (or just sheets of plywood) with holes in the middle to deposit the shells. New oysters need old shell beds to grow more bunches, so it’s important to return your shells for repatriation into the wetlands.

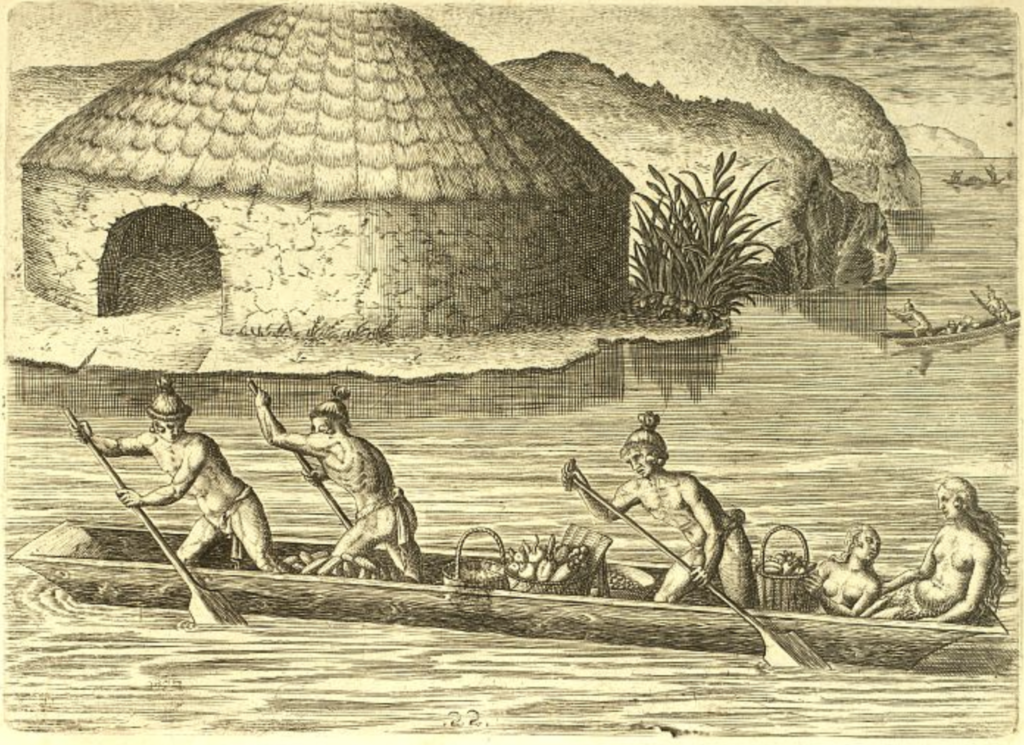

Native Americans also harvested the Lowcountry’s seafood bounty, evidence of which survives in the coastlines shell mounds or middens, “garbage piles made predominantly of shellfish remains but also containing other rubbish”, and which accumulated next to their settlement sites. There are at least fifteen rings along the South Carolina coastline. Archeological research in shell rings along the costs of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina” by the Florida Museum indicates that indigenous people thousands of years ago also limited summer oyster eating; “The seasonality of the shell ring may be one of the earliest records of sustainable harvesting, Nicole Cannarozzi said. Oysters in the Southeast spawn from May to October, and avoiding oyster collection in the summer may help replenish their numbers. “Understanding how people in the past interacted with and influenced their environment can inform our conservation efforts today.”

About forty minutes outside Charleston in either direction, the coastline shifts from developed to natural. The Sewee Shell Ring Boardwalk in Awendaw operated by the US Forest Service is a “one-mile, self-guided interpretive trail that dates back 4,000 years. The trail begins along a shady lane of trees which opens into an area heavily influenced by the forces of nature and man. A large portion of the area was scarred by Hurricane Hugo and wildfire. It is a picture of a land in recovery. The 120-foot boardwalk overlooks a prehistoric shell mound and offers five interpretive stops in addition to breathtaking views of the salt marsh, tidal creek and the Intracoastal Waterway.”

In the heart of the Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge near Seewee is Bulls Island, a beautiful, diverse, and protected landscape that includes a historic house site, miles of wooded trails, an expansive beach perfect for shell collecting, and even a prehistoric shell midden. Coastal Expeditions https://www.coastalexpeditions.com/bulls-island/ offers ferry rides to and from the island that are fully narrated to teach visitors about the island’s unique ecology and history. It’s common to see pods of dolphins on the way through the Intracoastal and protected waterways on the way to the island, and oyster banks nestled between the spartina grasses and marshes.

Coastal Expeditions’ website explains: Bulls Island is made up of 5,000 acres of land and it is the largest of the four barrier islands that are found within the National Wildlife Refuge of Cape Romain. The island is a teaming ecosystem that has sandy beaches, old maritime forests, both fresh and brackish waters, and salt marshes. It is also home to some of the most sacred and important trees in South Carolina like Magnolias, Palmettos, Loblolly Pines, and cedar trees. Don’t worry, with a landscape that rich, it is also home to a massive amount of wildlife. Other animals like dolphins, black fox squirrels, all kinds of fish, raccoons, deer, and alligators call Bulls Island home, too! According to the Refuge, over 290 birds have been recorded appearing on Bulls Island. Of course, one of its most popular destination locations through its 5000 acres is Boneyard Beach. The beach gets its historic name from the dead trees that have fallen on the beach and have been bleached white by the water and the Sun.”

The mosquitos and deer ticks can be fierce on the islands and in the nearby hiking trails of the Francis Marion Forest in the hot months, so late fall and winter are the optimum time to visit.

There are several campsites nearby with both RV and tent spaces, such as Buck Hall Recreation Area (part of the Francis Marion National Forest), which has trails and boardwalks, a large public boat slip, and tent sites overlooking the Intracoastal Waterway. Campers essentially have a tent-side fishing spot right next to their firepit and parking spaces. Buck Hall is also popular for shrimp baiting.

Oyster roasts in the nineteenth and early twentieth century were typically all-day activities, with beach walks or boat trips planned as part of the affair. For example, the Grand Lodge hosted a roast at Remley’s Point for visiting Masons in December 1897, and the “banquet of bivalves and etceteras” was followed by a trip around the Charleston harbor on the steamship Planter. In the 1930s, J. Swinton Whaley hosted the mayor and other dignitaries at his home on Edisto Island for “oysters served Edisto style”, and a late afternoon trip to Edisto Beach “to enjoy the beautiful sea breeze.”

Today, roasts are a popular fundraiser in the Lowcountry for various charitable organizations, so the feasting also goes to a good cause. Edisto Island Open Land Trust keeps off the season with their November roast, which supports land conservation and historic preservation initiatives for the beautiful island. On December 4th, Drayton Hall holds its Deck the Hall Oyster Roast along the beautiful Ashley River, with proceeds going toward the upkeep of the important colonial eera site. https://www.draytonhall.org/event/december-4-2022-drayton-hall-oyster-roast/ Tickets include all you can eat oysters, a chili bar, and local beverages.

The Lowcountry Oyster Festival a Boone Hall Plantation in January https://www.lowcountryhospitalityassociation.com/oyster-fest/ is Charleston Restaurant Foundation and the Lowcountry Hospitality Association’s “way to give back” by supporting local charities. Guests enjoy live music, raw oyster bars, roasts, shucking contest, a food court, and beer garden.

For a sit-down experience, there are a host of Lowcountry restaurants that offer fresh local oysters and accoutrement. If you’re visiting the shell ring on Sewee, hiking in the Francis Marion Forest, or are hungry after a day on Cape Romaine, journey a few miles further to Seewee Restaurant in Awendaw or to T.W. Graham’s, a McClellanville institution since 1894 that’s known for its fried local fare.

In downtown Charleston, Rappahanock in the Cigar Factory offers both local and imported Virginia oysters and a host of other seafood, while the Darling has a raw bar, and Leon’s Oyster Bar serves up fried oysters and chicken on Upper King Street.

Afterwards, visit the South Carolina Aquarium along the Cooper River for a special wintertime event called Aquarium Aglow, which runs November 18th-December 31st and lets guests “becoming immersed in waves of color from tens of thousands of lights. Installations, from warm and nostalgic to awe-inspiring and contemporary, transform the Aquarium you know and love. Combined with interactive displays and refreshments (food, wine and beer available for purchase).”

Contact Charleston Empire Properties today to learn more!

Sources:

- News and Courier, 12 January 1930

- News and Courier, 15 December 1897

- Florida Museum. “Only eat oysters in months with an ‘r’? rule of thumb is at least 4,000 years old.” https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/science/oysters-in-r-months-rule-4000-years-old/

- https://www.lowcountryhospitalityassociation.com/oyster-fest/

- Anderson, David G., Kenneth E. Sassaman, and Christopher Judge, eds. “Prehistoric South Carolina.” South Carolina Encyclopedia. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/prehistoric-south-carolina/

- https://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/scnfs/recarea/?recid=47387

- https://www.coastalexpeditions.com/blog/the-history-of-bulls-island/

- https://www.fws.gov/refuge/cape-romain/visit-us

- https://www.raynoronthecoast.com/?p=3608

- Susannah Smith Miles. “Lowcountry Oyster Roasts Northeastern Origins.” Charleston Magazine. https://charlestonmag.com/features/the_lowcountry_oyster_roasts_northeastern_origins

- https://scaquarium.org/aquariumaglow/

- “Sea Science: Oysters and Clams.” https://www.dnr.sc.gov/marine/pub/seascience/oyster.html