There’s nothing as ubiquitous and iconically Charleston than its namesake architectural form, the single house. There are thousands of these narrow residences in Charleston, in a variety of shapes, materials, and styles, built over hundreds of years throughout the city. But what are they, where did the concept come from, and why do they fit so well in Charleston? We’ll explore those questions and more in this blog.

Defining the single house

The Charleston single house style is vernacular residential form unique to the city that is easily noted by its narrow appearance. They are one room wide facing the street and have a central hall plan, and many have piazzas (a new comer might call them porches) running the length of the house. The front door into the house itself is found halfway down the long side of the dwelling, and opens into a central stair hall. The floor plan is usually replicated on each story.

The Charleston single house floor plan might be a diminutive two-story wood frame building, or three stories over a formal raised basement, or any size in between. Early examples were timber framed or brick masonry, while later examples from the early twentieth century were stick framed. They can be ornamented in any architectural style, such as Greek Revival, Italianate, Victorian, or folk variations. Charleston single house style was the most prevalent house type in Charleston from the eighteenth into the early twentieth century because they fit well on narrow town lots, and because they ventilate well (of upmost importance in a subtropical climate before the advent of air conditioning).

Visitors are often struck by narrow Charleston single house floor plan, like Philadelphia insurance man C.C. Hines, who wrote in 1860 that, “there are more little, old, odd, awkward buildings than I ever saw in a town before!” He clearly didn’t do the architectural creativity or character of the single house justice, but he was right about their uniqueness- this is the only place in the nation where one finds a single house, or as a tourist would say, a house “turned sideways” on its city lot.

Origin Stories

There’s an ongoing debate about whether the Charleston single house style is homegrown or came to the Lowcountry by way of Barbados, but there’s justification for both theories or a mix of both. Charleston has other Caribbean influences, like the pastel colors of our houses, which help reflect heat better than a dark paint color. Many of Carolina’s earliest English settlers came to the colony by way of Barbados, where there was a similar narrow house form. Though only a scant few survive there, it’s possible that homes like the Arlington House in Speightstown, Barbados are the foundation for the single house idea, brought here by Bajans turned Charlestonians. Charleston single house style by their narrowness allow air and breezes to circulate easily.

Others point to Charleston’s narrow lots, which started out larger and were subdivided into smaller parcels often just thirty feet wide or less, as the reason for the Charleston single house’s creation, or at least for its prevalence. A benefit of the single house is that it is a stand-alone city dwelling that offer private yards and frontage for each detached building. Singles proliferated after the great fire of 1740, a dangerous conflagration that swept the city, easily jumping from one wood shingle roof to the next because many early row houses shared partition walls. Single houses stand alone, and their driveways act a convenient fire break between the narrow houses.

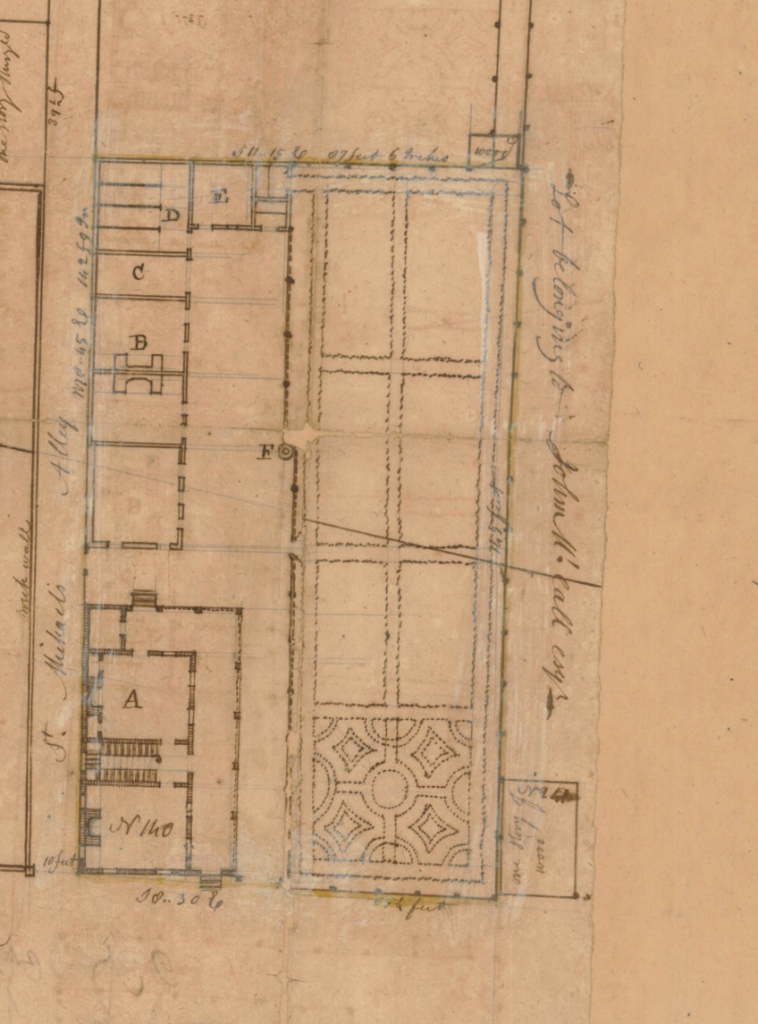

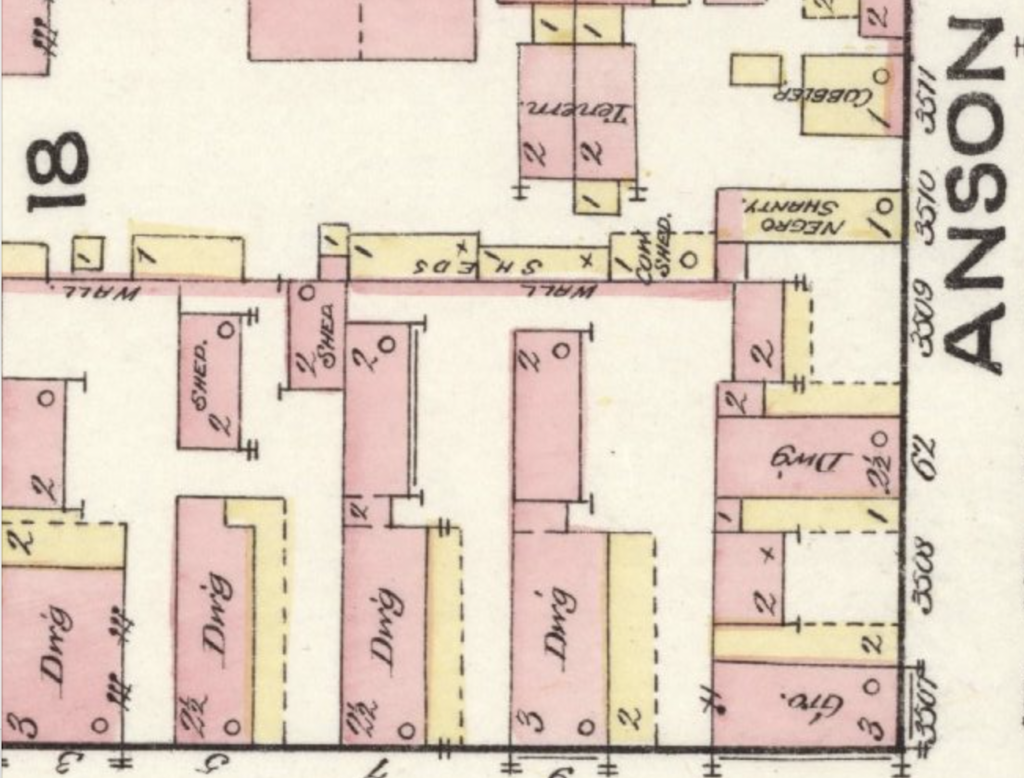

Lot placement and Layouts

One of the beauties of the Charleston single house floor plan is that its narrowness allows both street frontage and a side driveway, while many other early town houses either take up the whole lot and share party walls, or are placed in the center of the lot, leaving little room for passage on either side. Charleston single house style are usually placed right on the sidewalk. A piazza door opens into the private realm, leading onto the piazza to the door into the house. Alongside the piazza is a street gate to the side drive, which usually leads to a rear yard with outbuildings that might include kitchen houses, slave quarters, and carriage houses and stables turned into garages. Historians have described single house lots as “urban plantations” because they are self contained to control the coming and going of previous enslaved inhabitants, and because of their collection of support buildings.

Charleston single house style follow a pattern along the street – house, piazza, driveway – and the piazzas all face the same direction, south or west, to catch the sea breezes and give residents a bit of privacy while they are on their piazzas. There’s only a few curious examples in the whole city where two piazza face each other.

Dressing Up

The easiest way to tell the style and age of the Charleston single house style is by the ornamentation used around the piazza door and on the piazza itself. The earliest colonial examples often had beaded wood siding, windows filled with small panes of glass, and understated elegance. Greek Revival examples boast large Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian columns and square sidelights around the door, while Italianate examples have delicate Roman Renaissance inspired features and maybe even a rare arcaded piazza. As styles and lifestyles changed, residents altered their facades in the latest tastes. Victorian single houses often have more adornment, a bold multi color paint scheme, and projecting bay windows on the façade. Others are almost minimalist in their pragmatic, under ornamented, working-class iterations.

The interiors are as diverse as the people who lived in and remodeled their Charleston single house style over the years, but the front parlor on the street, “the best room”, is usually the most ornate, with the fanciest molding and mantels in the house. Today, the front parlor is the most likely to be period furnished, giving guests a glimpse of earlier Charleston single house style entertaining spaces. Across the central stair hall (which serves as a great place to add a powder room, tucked below the stair) is the second, less formal parlor. Upstairs holds the bedrooms, and another series of parlors for a three story single, and there might be another small bedroom or two tucked into the garret in the attic and lit by dormer windows that offer quaint rooftop views.

Freedman cottages

Really a form unto itself, the humble freedman’s cottage resembles a single house in plan but is a single story instead. The diminutive houses proliferated after the American Civil War and were home initially to newly emancipated Black Charlestonians, giving rise to the name Freedman’s cottage. Many were built by developers, often several on a lot with a small court cut through for access, and were rentals, but some were built by working class Charlestonians and were owner occupied. Like singles, the cottages can be found throughout the city, even tucked away South of Broad on Stoll’s Alley, and they could be ornamented as much as the owner desired or left plain. Most are wood frame, and date from about 1870 to 1920. The largest concentrations are found in the East Side and Cannonborough-Elliottborough, which were integrated neighborhoods of workaday residents and tradespeople. Most have additions to allow modern conveniences and more space, but Freedman’s Cottages are essentially early tiny homes, and they function quite well even at their original size of about 400 to 600 square feet. Visit the Jackson Street cottages in the East Side, which have been converted into businesses like Tobin’s Market and Port city Media, to see the circa 1890 interiors up close.

Modern takes and renovations

Many of the earliest Charleston single house style didn’t have piazzas or had only a single-story verandah. Owners added second story piazzas to maximize outdoor living space and catch breezes above the dusty street level. With indoor plumbing and electricity, residents abandoned rear outhouses in favor of in door bathrooms, often constructed on part of the piazza. They also attached their kitchen houses to the main dwelling with passageways or hyphens so they wouldn’t have to go outdoors to cook, once fire was less of a threat.

The Charleston single house floor plan is adaptable and easily updated, which meant that many of them were altered in the mid twentieth century with materials that are not historically accurate, or worse, were neglected during the decades before Charleston’s post Hurricane Hugo heyday.

45 Cannon Street is a prime example of a Charleston single house floor plan changed over time, and then carefully renovated to its former glory by Charleston Empire Properties. The Charleston single house style sits in Cannonborough-Elliottborough and was built around 1900 by the Kugley family. Catherine Lewis bought the house in 1919 and converted the first floor into a business space, where she briefly operated a grocery before renting the space to a series of African American operated businesses, including Joe’s Lunchroom (which attracted occasional crime and excitement in the 1930s), Fletcher Lunch Counter, and Robinson’s Soda Fountain Luncheonette. Lewis was responsible for subdividing the lot, and another building was tucked in next to 45 Cannon, explaining why the quaint little piazza is so close to the neighbor. The meticulous renovation turned the Charleston single house floor plan back into a residence, with several bedrooms, beautiful custom kitchens, spacious new bathrooms, exposed historic ceiling joists, warm wood floors, and shiplap accent walls.

Styles come and go, but Charleston single house style are still a practical form and plan for new houses tucked onto vacant lots in the city, and developers even use them in suburban communities because they exude Charleston character. Architects who favor contemporary design create minimalist and even modern takes on the Charleston single house floor plan, or use streamlined surfaces and glass walls to differentiate new additions from an earlier single house that is being updated. Most new-build Charleston single house style are bigger than the originals, with large rear bays or truncated piazzas to allow more interior living space, showing just how adaptable the iconic single house is.

Discover the charm of Charleston single houses for sale in Charleston, SC with Charleston Empire Properties. This iconic architecture features a narrow, yet elegant design with a spacious interior. Experience timeless Southern beauty and modern comfort combined in one unique package.

Ready to find your dream home? Contact Charleston Empire Properties today to explore these historic treasures and start your journey to refined living.

Sources:

- Jay Edwards. “Open Issues in the study of the historic influences of Caribbean architecture on that of North America.” Material Culture. Spring 2005, Vol. 37, No. 1, 44-84.

- Bernard Herman. “The Embedded Landscapes of the Charleston Single House, 1780-1820.” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, 1997, Vol. 7, 41-57

- McCrady plats and Charleston County deeds office plats

- Jonathan Poston. Buildings of Charleston. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

- Severens, Kenneth. Charleston Antebellum Architecture and Civic Destiny. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1988.

- Waddell, Gene. “The Charleston Single House . . . An Architectural Survey.” Preservation Progress 22 (March 1977): 4–8.

- Christina Butler. “History of 45 Cannon Street.” For Charleston Empire Properties, 2019.

- Daniel J. Vivian. “Charleston Single House.” South Carolina Encyclopedia. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/charleston-single-house/

- Jefferson Kolle. “Charleston Single House: Built to Last.” This Old House Magazine.

- https://www.charlestonlivability.com/charleston-single-house

- Lissa D’Aquisto Felzer. The Charleston “Freedman’s Cottage”: An Architectural Tradition. Charleston: History Press, 2008.

- https://jacksonstreetcottages.com

- https://barbadosnationaltrust.org/project/arlington-house-museum/