Boasting the largest historic district in the United States, Charleston is known for its beautiful architecture and charming streetscapes. The icing on the cake are the buildings’ intricate iron gates, fences, and balustrades. Architectural ironwork is seemingly delicate but stands the test of time and speaks to centuries of dedicated and talented craftsmen who have custom designed and hand forged the architectural metalwork found throughout our historic city. Thanks to English trained smiths in the eighteenth century, German ironworkers like Christopher Werner in the antebellum era, Philip Simmons, who kept ironwork traditions alive in the twentieth century, and the next generation of blacksmiths working in the city today, Charleston is brimming with fabulous ironwork that is sure to delight.

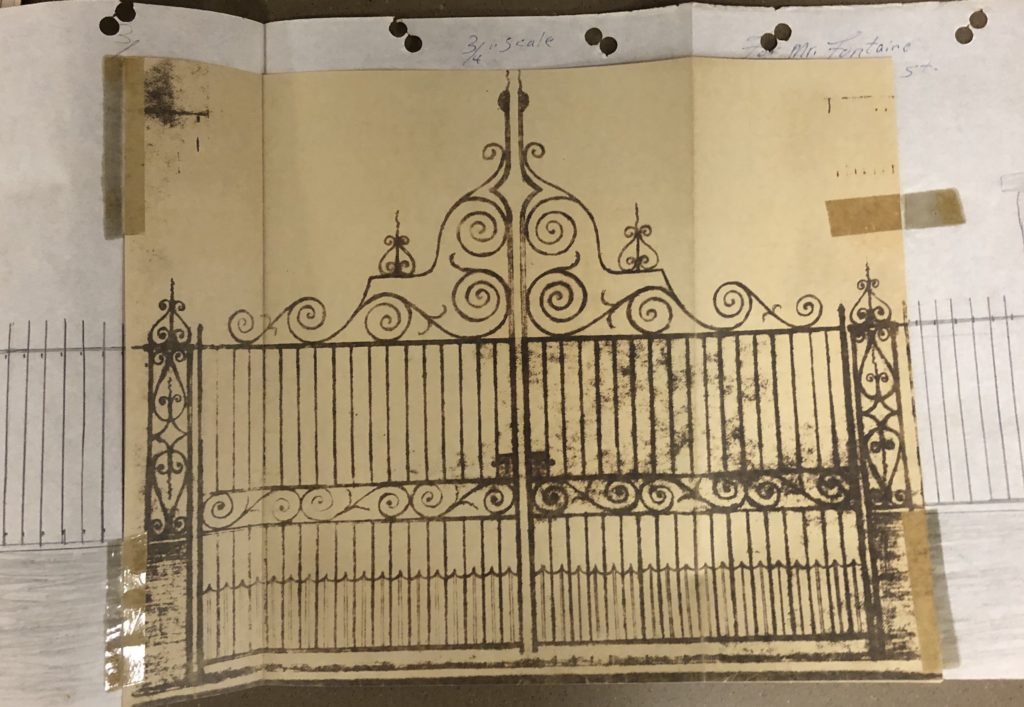

Until the nineteenth century, virtually every piece of ironwork- tool blades and saws, nails, hardware and hinges, fencing, and ornament- were completely handmade, and mostly hand forged of wrought iron. Wrought iron is created by heating iron ore with charcoal to burn and beat (hence the term ‘hand wrought’) the impurities out of the metal. Iron has a natural grain and can be strengthened by reheating and forging. Next, blacksmiths hand shaped the iron into beautiful and useful ornament and architectural pieces. Most smiths today used a low strength steel, which is stronger and has a lower carbon content, but can be bent and forged into the same shapes as traditional wrought iron. Another popular practice is casting iron, which is made by melting iron and pouring the molten material into forms. Cast iron is made in a foundry and because it is poured into a mold, it’s possible to create delicate, three-dimensional features. Forged iron, by comparison, uses bars of metal and is completely hand forged. The iconic scroll work with delicate tapering ends found in Charleston’s most famous gates are forged.

Charleston’s earliest blacksmiths were English born and trained, like Thomas Lovelace, who advertised in the 1730s for making tools, or James Linguard, “a smith and farrier [horse shoer] who makes all kinds of scroll work for grates and staircases” working in the 1750s. Merchants also imported ornamentation directly from England, to be customized as needed and installed by local smiths. Local craftsman turned to architectural illustrations of the latest pieces coming out of London to design pieces for their wealthy Charleston clients. Sadly, due to wear and tear, stylistic changes, rusting, and metalwork being salvaged for cannon fodder during times of war, there are only a few known eighteenth century pieces of ironwork left outside in Charleston. The railing in front of St. Philips Church and the intricate scrolled lamps at South Carolina Society Hall on Meeting Street are both believed to date from the 1760s.

Many of Charleston’s tradesmen were enslaved, and ironworking was no exception. A 1769 advertisement for blacksmithing services provides the names of a few of these talented men: “Billy, 22, is an ‘exceeding trusty good forge man as well at the finery as under the hammer, and understands putting up his fire’; Mungo, 24, is a good firer and hammer man; Sam, 26, a capable chafery hand; Abraham, 26, reliable forge carpenter; Bob, 27, thoroughly understands the duties of a master collier.”

Nineteenth century Charleston boasted several talented ironworkers who ran foundries for casting and hand forged pieces as well. Jacob Roh and eight assistants made the breathtaking gates for St. john’s Lutheran Church, while J.A.W. Justi made the gates for St. Michael’s Church. German-born Julius Ortmann loved to put a lyre motif in his pieces, making them easy to spot. Ironwork at City Hall features S curves and a lyre design, possibly by Ortmann. Washington Park next door has some of the most beautiful gates in the city, and an imposing but elegant wrought iron and brick fence around the periphery.

Born and trained in his father’s carriage making shop in Muenster, Germany, Christopher Werner (1805-1875) became the most prolific smith in the city after he arrived in 1828. Werner did the fencing around Randolph Hall at the College of Charleston, made shop sign hangers and awning brackets, advertising in 1859 as a “manufacturer of railings, verandahs, and fancy iron works generally, together with repairing and smithery of all kinds.” When Thomas Gadsden renovated the John Rutledge house in 1853, he hired Werner to cast the lacy New Orleansesque railing and verandahs, which have palmetto tree motifs in them.

Werner also made the famous Sword Gates at 32 Legare Street. Made in 1838, they are his earliest known extant work. They were originally intended for the New Guard House, but Werner mistook the order for a pair of gates to be two sets of gates and made too many. One set at the Citadel, and British consul George Hopley bought the other in 1850 and installed them at the Sword Gates house.

Werner also created the striking black wrought iron crucifix that marks the entry to St. Lawrence Catholic Cemetery, which along with neighboring Magnolia Cemetery, are some of the best places in the city to view traditional ironwork. Family plots are bordered by beautiful cast and forged fences, next to the picturesque Cooper River marshes.

There were a few large foundries in antebellum Charleston with machine shop areas, which could fabricate industrial goods like streetcar lines or shipping equipment, in addition to architectural pieces. Eason Foundry on Columbus Street operated by Irishman James Eason and the Phoenix Foundry on Hasell Street each had a large lathes and could make steam boilers. William H. Henery’s foundry and blacksmith shop opened in 1853 and boasted a special metal punching machine that would pierce 20 holes a minute in iron plat up to ½” thick, but they also made pillars for Charleston buildings. After fire destroyed Christopher Werner’s foundry in 1858 (along with thousands of dollars of intricate patterns and grillwork) he managed the casting and wheelwright shop for Vulcan Iron Works (owned by Archibald McLeish.)

Cast iron was especially popular in the mid nineteenth century, with examples from Charleston to London to the cast iron district in New York City. Historian Michael Vlach explains, “During the second half of the nineteenth century, more and more cast-iron elements were used to embellish Charleston’s iron gates and fences. These mass-produced elements were created mainly in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston and shipped south to satisfy the new demand for solid, lifelike replicas of flowers, leaves, and branches that were favored during the Victorian period.” Greek keys and other Greco-Roman motifs were all the rage.

Traditional ironwork, along with plastering and stone carving, was gradually replaced by mass produced ornament in the twentieth century. Sadly, many of the secrets and master techniques were lost as older generations retired. Vlach explains, “during the Great Depression, when the prospects of all industries were dreary, the demand for the skills of ornamental specialists was especially feeble. During this period general blacksmiths, men who mainly shoed horses and did repair work, occasionally stepped forward to take on the challenge of decorative commissions.” Philip Simmons, one of the most iconic smiths of the twentieth century, kept the traditions alive and passed his skills to a younger generation. Simmons was born in 1912 on Daniel Island to an African American family of farmers. The family moved to the city and by age 12, Simmons was enthralled by the sounds and sparks coming from Charleston’s iron shops, and knew he’d found his calling. He apprenticed with blacksmith Peter Simmons (no relation), who was a farrier and wheelwright who also made architectural ironwork. By 1938, Philip decided that architectural ornamentation was his strong suit, and he quickly became the go-to craftsman for traditional ironwork in the city. Simmons repaired historic pieces and also designed and fabricated beautiful new gates using traditional methods and motifs. The “sword gates” at the Gadsden House on East Bay Street are one of his most famous pieces, a design collaboration with architectural historian Samuel Stoney that references Christopher Gadsden’s famous “don’t tread on me” flag.

The Simmons Foundation, a non-profit organization that maintains the Simmons Commemorative Heart Garden in Ansonborough and works to preserve Simmons’ legacy, notes that he fashioned more than 500 pieces of ornamental ironwork during his long career. In 1982, the National Endowment or the Arts awarded him the National Heritage Fellowship, “the highest honor the United States can bestow on a traditional artist.” Simmons’ work can be seen in the Smithsonian and throughout our historic city. His house and forge on Blake Street in Charleston’s East Side are now a museum, and young blacksmithing interns can be seen working their occasionally during the summer. Simmons is immortalized in bronze in the center of Hampstead Mall, the oldest greenspace in the city just blocks from his shop, in a statue that depicts him holding his hammer and working at the anvil. Ade Ofunniyin, Simmons’ grandson who passed away tragically young in 2021, apprenticed in the blacksmith shop as a young man and proudly shared his family’s history with others through the Gullah Society (which he founded) and through his graduate research connecting his “family’s blacksmithing business with blacksmithing traditions in Africa.”

Philip Simmons is also the inspirational founder of the American College of the Buildings Arts, founded in 1998 to keep traditional building trades alive. The college is located on upper Meeting Street in the historic trolley barn building where streetcars were once repaired. ACBA is the only college in the United States offering a four-year liberal arts degree with a focus in several traditional trades- timber framing, architectural carpentry, classical design, stone carving, plaster, and blacksmithing. At ACBA, “iron students are introduced to age-old techniques while also learning the new innovations and practices. Wrought ornamental iron, gates, fences, balconies, railings and many other built-in decorative elements are among the techniques and skills learned in our apprentice labs, which also include the ability to forge, join, and weld materials to create unique objects of utility and beauty that enhance their architectural surroundings. A skilled metal artisan is able to forge, join, and weld materials to create unique objects of utility and beauty.” Visitors are welcome to drop by the campus, where they can view Charleston’s latest ironwork in the process of being forged.

Sources:

- acba.edu

- http://www.philipsimmons.org

- Vlach, John Michael. Charleston Blacksmith: The Work of Philip Simmons. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1981

- Library of Congress photograph collection

- Historic newspapers

- Simons, Albert and Alston Deas. The Early Ironwork of Charleston. Columbia: Bostick and Thornley, 1941

- Bayless, Charles N. Charleston Ironwork: A Photographic Study. Orangeburg: Sandlapper Publishing, 1987.

- Lyons, Mary E. Catching the Fire: Philip Simmons, Blacksmith. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997.

- Ciocola, Katie. Werner Fecit: Christopher Werner and Nineteenth Century Charleston Ironwork. Clemson Masters in Preservation thesis, 2010.

- Vlach, John Michael. “Charleston Ironwork.” South Carolina Encyclopedia. April 2016. https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/charleston-ironwork/

- http://www.thegullahsociety.com/dr-ade-ofunniyin-dr-o.html